As a writer, I’ve always worked at home. Now, because of the pandemic, my wife and twin boys also are here with me. I’ve gotten along with them okay, but they’ve noticed something I’d hoped they wouldn’t. I don’t “work” as much as I should.

I am supposed to be drafting my second work of non-fiction. Something big, something important, something accomplishing what the first book promised to do and nearly did achieve. It was a finalist for every major literary non-fiction prize in the country but just couldn’t nab the win. These past few years, I’ve tried to one-up myself. I’ve tried to fulfill my potential.

I haven’t.

Emmet, two minutes younger than Jack, was the first to say something. “You’re playing World of Tanks. All day, Dad.”

I could have said, “A writer is always writing even when they aren’t writing.” I probably did. It’s an adage shared among authors to soothe feelings of guilt, and it’s often true. A walk, a shower, a full binge of every season of Full House can lead a writer to felicitous insights about their current project. But I grind for hours on World of Tanks. I fight random battles on my computer against other online players across North America. I won’t divulge my handle. You would be dismayed by my online behaviour if you, as a teammate, failed to stop enemy light tanks from roving on our flanks. I never mean to swear so much or play all day long. I often do, and no real work gets done.

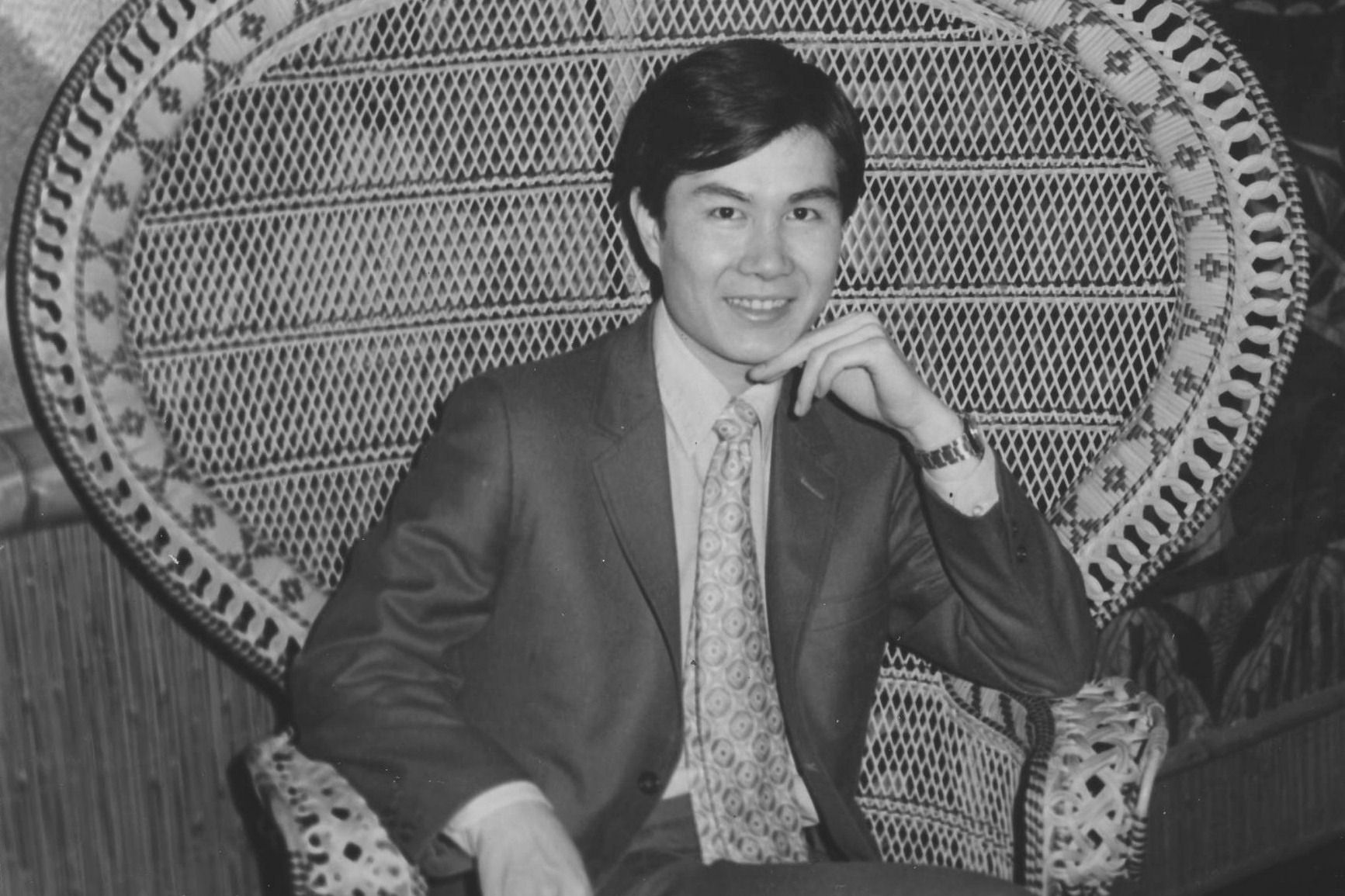

Photo courtesy of JJ Lee.

Before World of Tanks, I threw myself into a series of “projects.” Rewiring electric guitars. Converting banjos into tenor guitars and acoustics into electrics. Soldering output jacks to tape heads to create screeching amplifiers. Assembling computers from scrap parts and attempting to make them process at speeds beyond their recommended limits (one CPU, an AMD A8-5600K, got so hot it smelled like incinerated hair). Did I mention I build functional instant cameras out of LEGO?

The strange part is I like working. I teach non-fiction to a select cohort of writers at Simon Fraser University. I look after our apartment complex when the building manager goes on vacation. A few years back, I took shifts as a clerk at the last video store in my town. These days, I fantasize, after the lockdown, about slinging steamed hotdogs at the joint around the corner. Put me onto some menial task, and I just whistle away.

My father worked like a dog. As a teen, I hardly ever saw him. He spent all hours of the day and night at some Montreal restaurant or another. At the height of his success in food services, he owned a chain of restaurants called Proportions. They served New Age deli meets California cuisine. Think crabmeat cocktail on a bagel. It wasn’t kosher, but it attracted mostly Jewish people, about whom my father, in those few times he and I spoke about his work, readily expressed disdain.

One late night he brought home a new set of menus, each a single 11-by-17 card under plastic. They were printed in black, red, and, because it was the mid-’80s, turquoise ink. Little drawings evoking Sonoma vines decorated the corners. There was a grid resembling block glass. Very po-mo. Truly of its time. I think I may have asked him what capers were. I do remember him suddenly spewing that the diners were cheap, complained too much, and had no class.

My face burned. I said, “They’re your customers.” I had to squeeze the words out.

My father was a man who would take someone else’s money with the absence of joy, respect, and, I mean this, love. I resolved never to do this.

When I had a slender moment of what a neighbourhood used-bookseller called “Canadian writer” fame, interviewers asked all sorts of odd questions. “What is my idea of perfect happiness?” “With which literary figure would I most like to share a meal?” “Batman or Superman?” Okay, I made the last one up, but it was that kind of stuff. One I was never prepared to answer is, “What was the worst job you ever had?”

I have sold multi-modal through cold calls. I have painted tiny ducks in an industrial park so remote I couldn’t possibly tell you then or now its location. I have worked as a traffic reporter despite never having learned to drive. I’ve been bad at jobs. I’ve gotten in trouble at the office. I’ve done things on the sales floor I wish I could undo. I’ve hated being bad at a job, but I’ve never hated a job itself. I suppose I’m lucky.

Photo courtesy of JJ Lee.

But since I’ve dedicated myself to full-time writing, in pursuit of a second, life-altering work of non-fiction, I’ve only made progress in computer building, guitar tech’ing, and World of Tanks. The writer’s block doesn’t kill me. Being a poor role model and a poor father does. What lessons do I teach them?

I’ve talked quite a bit to Emmet and Jack about my father, their grandfather, who died two years before they were born. That’s what my first book was in large part about. They know that he drank (I rarely do), was prone to violence (only my tongue), and killed our family dog (thank God, never). They know, despite my father’s grave faults, that I yearned for his time and attention. He could offer me neither, of course (but I have done my best to be around). I admit it doesn’t take much to be a better dad than my father, but I sure as heck let the boys know that I am.

The other day, they complained about their online high-school workload.

“If you didn’t fucking waste all your time screwing around, you wouldn’t be behind,” I said.

One of the boys responded, “What about you?”

Indeed, what about me? Ever watchful, my sons have seen my flailing and distraction.

So I’ve started to close the bedroom door. That’s where I work. Before it fully shuts, I say down the hall, “Leave me alone. I’m writing.”

But what mostly swirls in my head are my father and me, my sons, love and money, repelling magnetic poles that need to be flipped right.

The past few weeks I have mostly worked on other people’s manuscripts. Former students have been submitting to agents, editors, and publishers. I’ve helped them put a polish on things, strategize on how to pitch, counselled on how much to ask. A member of my writing group just completed a massive project. She asked, “Will you read it?”

“Sure,” I said.

“I’ll pay you.”

I had to decline. It was 500 pages.

“It’s a lot of work,” she said. “I would feel guilty if I didn’t pay you.”

I couldn’t accept. I couldn’t understand why I declined. And all the other million times I’ve bargained myself out of a payday.

I’ve only discovered it after I shut the door.

I used to think, if I took money from a writing friend, it would make them love me less.

But that’s not really my problem. What actually drives me to say no is that the money will make ME love THEM less.

I would see them as income instead of as friends. I am susceptible. This past decade I’ve only made between $22,000 to $27,000 a year. There have been a few windfalls that have made me feel like Croesus, but mostly I rely on my wife to keep food on the table. When you’re that desperate, you can become grasping, feral, predatory. You can reduce others to being a mark, a revenue stream, a bag of money. I fear all of this in my blood. That I would be my father. So I decline to be paid. Thousands of dollars.

I don’t know what the boys make of me.

I can’t say that I know myself. What lessons from me do they take?

At supper last night, we started talking about great meals. Emmet and Jack raved about a visit to the wonderful bakery Pure. How its counter ranged like mountains with cakes, breads, and cookies. It was an exquisite place to eat, unlike our dining table, which is now crowded with computers, wires, and papers. I asked Jack if he remembered Frank Fourchalk.

“Who?”

“When you were little, you couldn’t go to daycare or school. I had to tape a documentary about home security, and he was an expert. And we had to take a bunch of buses to get to him. Do you remember?”

Jack didn’t.

That day we spent hours on transit because, as I’ve mentioned, I don’t know how to drive. We transferred three times, and we had to walk a kilometre as well. I spent the afternoon with Fourchalk. I think he showed me how to break into a house. Jack watched cartoons with Mrs. Fourchalk. He didn’t make a peep. It took another three hours to get to downtown Vancouver. It was 9 at night. Jack hadn’t eaten dinner.

The bus pulled up kitty corner from the Hotel Vancouver. I took Jack’s hand, and we marched into the lobby. The lounge was filled with business travellers. Light glittered off crystals, cutlery, and the bottles in the bar. My father loved places like this.

At the Giller Prize watch party. Photo courtesy of JJ Lee.

I asked the host if my son could eat with me in the lounge.

He said, “No, sir. But we can accommodate you in the south lounge.”

It was the tea room. It was dim and entirely empty. Jack and I sat on a couch in the middle of the vast space. We decided on fries and sliders. Jack took in the room and said, “Fancy.”

In that moment, I could feel my father in me. The very best part of him. When I was a boy, he brought me to some of the most elegant establishments in the city and made me feel like a prince.

“Do you remember?” I asked Jack at supper.

He squinted. The chandeliers and the curved gilt ceilings of Hotel Vancouver came back to him. Did he recall that I told him that he worked hard, that he was very good, and that I was so proud of him?

He said, “Yeah, I do.”

I felt relief.

I haven’t quite fulfilled my potential. But honest to God, I’m working on it.

Read more Essays.