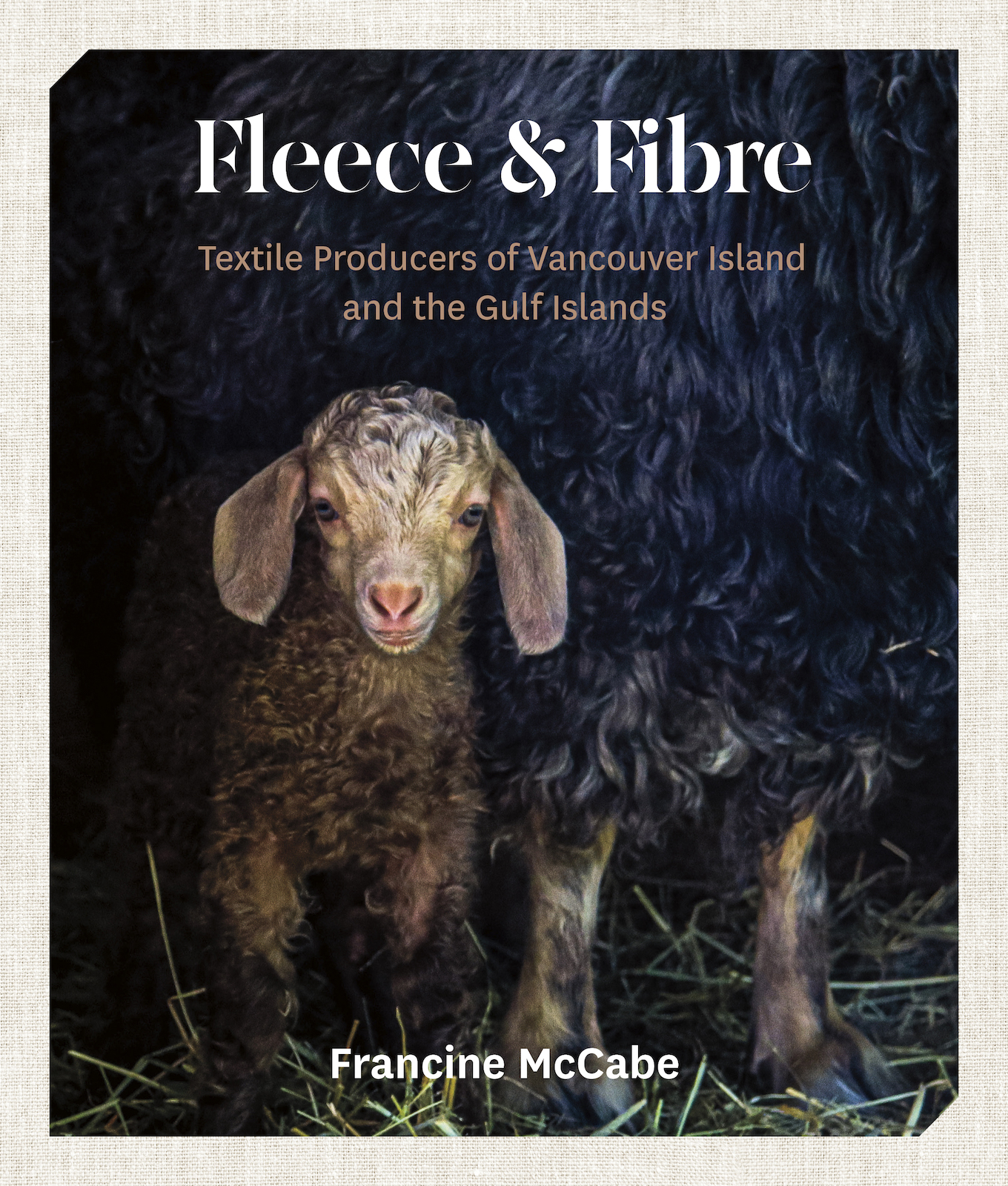

Fibre artist Francine McCabe is a member of the Vancouver Island Fibreshed network. What is a fibreshed? In her new book, Fleece and Fibre: Textile Producers of Vancouver Island and the Gulf Islands, McCabe writes about how some of British Columbia’s small-scale textile farms are networking to help process and share their products.

On Gabriola Island, the nearly two-hundred-acre Islandia Farm is a designated Century Farm, one of the oldest in our region, raising sheep since the early 1850s. When the farm was first established and prospering, it was one of the main food suppliers to the Nanaimo coal mine industry, shipping fresh meat and vegetables to feed the workers.

In 1994, Russell Hollingsworth and Arabella Campbell purchased a portion of the property with the intention of restoring it and increasing the food, livestock, and hay productivity. Recently, they were able to acquire the remaining portion of the land from the original family and are continuing to re-establish the homestead.

To access more of the property, Russell and Arabella have used an ancient engineering technique used by the Romans and revived recently in Scotland. Waste wool is laid down as the initial foundation for roads and walkways, acting as a barrier between the wet, soggy land and the stone surface laid overtop. The wool is an eco-friendly replacement for the common plastic membrane, allowing moisture to pass through without washing away roads.

Laying wool for road stability at Islandia Farm. Photo courtesy of Russell Hollingsworth and Arabella Campbell.

The farm currently houses a flock of sixty North Country Cheviot × Suffolk. Sheared in June, the flock is predominantly white with some brown-black in the mix.

Both Arabella and Russell are passionate about traditional crafts and small-scale circular production. They share with me that “at Islandia Farm, we see natural wool fibre as a wonder of nature and a potential panacea to the damage caused by the micro-fibre industry.”

Vancouver Island and the Gulf Islands have hundreds of farms currently breeding sheep, alpacas, llamas, goats, and other fibre-producing animals. I spent over a year sourcing island fibre and visiting thirty-one farms and their fibre animals. My journey began in early fall, on one of those days on the island when the fog is so thick the land disappears under a smothering cloud. My family and I were out on a weekend adventure, driving up the Old Island Highway to explore a new area. Once we were out of the fog, I counted several farms with sheep, goats, and acres being readied for the coming season. It seemed obvious to me that the island would be producing its own fibre.

Young Suffolk ewe at Tsolum River Ranch. Photo by Francine McCabe.

Later that week, I visited a few of my favourite yarn shops and discovered that they had little to no local fibre. When I asked the shop staff why, they all told me the same thing. By the time the farmer has the fibre processed and packaged into yarn, the cost is already high. Once the shop adds enough markup to make a profit, the price is beyond what most consumers will pay.

Flock of Suffolk sheep grazing at Tsolum River Ranch. Photo by Francine McCabe.

This left me wondering: Why was local fibre so costly to produce? I discovered that Vancouver Island once had several small family-run fibre processing mills, but I couldn’t track down any existing ones. Today, farmers looking to process their fibre have no other option than to ship their fibre off the island, sometimes even across the country, for affordable processing. With the huge variety of fleece and fibre on the island, both animal- and plant-based, I was shocked to find no operating mills.

The problem was certainly not a lack of fibre. The more I searched for local fibre, the more amazed I was by the variety of breed-specific producers. Each resource led to another, and soon I had a long list of farms that were breeding fibre animals.

Yet with all this fibre being produced, I still didn’t know where it was all going or how I could get my hands on it. And I really wanted to get my hands on it! So, I did the only other thing I could think of: I started knocking on doors and contacting people by phone or email.

Sheep being sheared at Parry Bay Farm. Photo by Francine McCabe.

Along the way, I kept hearing similar stories of processing woes and the growing cost of feeding and caring for animals. This made me wonder: Why aren’t we, as a province, investing more in fibre infrastructure? Why are there multiple agricultural grants for farmers looking to produce food, but so little financial help for starting fibre-related farms? We need sustainable start-up options for fibre mills. Fortunately, we are beginning to realize that our textiles are just as impactful to our region as the food we eat. Closing this gap is one of the goals of the fibreshed movement.

Freshly shorn fibre at Parry Bay Farm. Photo by Francine McCabe.

The fibreshed concept was pioneered by Rebecca Burgess, M.Ed., executive director of the California-based non-profit organization Fibershed. (You’ll notice two different spellings: “fibre” in Canada and “fiber” in the US.) She defines “fibreshed” as “a vision that enhances social, economic, and political opportunities for communities to define and create their fiber and dye systems and redesign the global textile process. It is place-based textile sovereignty, which aims to include rather than exclude all the people, plants, animals, and cultural practices that compose and define a specific geography.”

North Country Cheviot ewes coming down from the hill at Conheath Farm. Photo by Francine McCabe.

Burgess’s concept made so much sense to me. I realized I was far from the first person to be asking these questions about local fibre and the growth of a regional textile economy. Her concept has quickly spread, and networks have begun popping up all over the world. Rich in fibre resources, Vancouver Island and the surrounding Gulf Islands incorporated in 2018 into the fibreshed movement.

Still, farmers need an easy way to turn their fibre over so they can justify and afford the time spent on the product, and the makers that are looking for local fibre need to know what is locally available and how they can buy it. All the parts are here; they just need connection.

Pile of wool being given away for free. The farmer intended to bury any wool not taken. Photo by Francine McCabe.

Farmers themselves, however, are working hard to close gaps. Each farmer in my book, Fleece & Fibre: Textile Producers of Vancouver Island and the Gulf Islands, made it clear that using all the materials from their farm in a renewable way is important to them and their farm practices. I saw fields of flax used as a dual-purpose cover crop. I met farmers with fibre mill plans in the works. One farmer told me about a new wool pelletizer she just purchased. Others are using their wool as building insulation.

Handmade textiles. Photo by Francine McCabe.

What these farmers are doing to care for their animals, crops, and the land is invaluable and deserves to be shown off. And the products they are bringing to our local market are worth supporting and nurturing. Everyone I met along the way has been so enthusiastic about fibre and the possibilities. They give me hope.

Excerpted from Fleece and Fibre: Textile Producers of Vancouver Island and the Gulf Islands by Francine McCabe (Heritage House, 2023), reprinted with permission of publisher. Read more Impact stories.