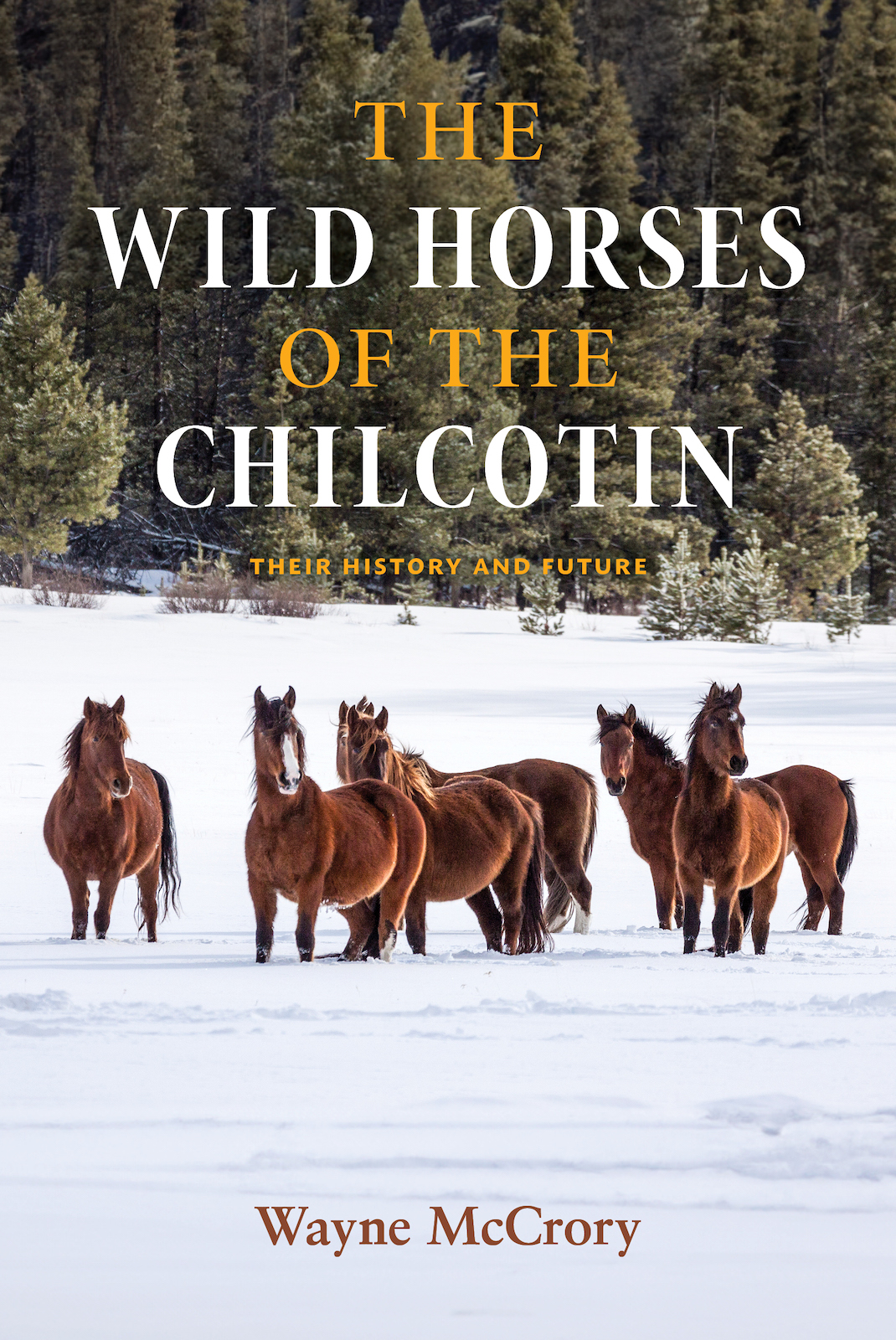

In this excerpt from The Wild Horses of the Chilcotin: Their History and Future, wildlife biologist Wayne McCrory describes historical efforts to rid British Columbia’s Chilcotin region of these wild animals.

Early in my research on Chilcotin wild horses, I quickly learned that the debate around the Chilcotin horse, grizzly bear and wolf killing fields was, and still is in some quarters, characterized by deep prejudice, if not downright animosity, against these last wild horses and large carnivores. I also found that evidence used to eradicate wild horses and large predators could charitably be called slim, full of misinformation and speculative, unproven claims.

While there were many efforts to address range degradation by cattle during the century-long war against the horse, for a variety of reasons it was always easier to focus on the less powerful and less economically valuable claims on grassland by wild horses and other creatures that settlers considered pests.

Government-sanctioned ranchers’ weapons against these so-called pests included bullets, bounties, snares, roundups, poisoned baits laced with strychnine, and leg-hold traps. The choice of method depended on whether “the enemy” was wild horses or large predators.

According to John Thistle, “The common connection and the point of killing animal pests, such as grasshoppers, wild horses, coyotes, bears, cougars, and numerous other species, were at least partly to claim territory—in this case land and resources—for the colonial state and for immigrant ranchers and their cattle. As part of the range cleansing, First Nations that had occupied the grasslands for countless centuries were unjustly forced on to small reserves, with no Treaties ever being negotiated.”

Since first being introduced by the Tŝilhqot’in about four centuries ago, the Chilcotin wild horse has been able to roam free and thrive within a fully functioning predator-prey ecosystem.

This settler monopoly of the grasslands still exists today, leaving little or no room for the restoration of Indigenous traditional uses of their original commonage landscape; it prevents careful rewilding and coexistence with wild horses, wolves, grizzly bears and a multitude of at-risk grassland species. An exception occurs in the more remote areas of the West Chilcotin where the Xeni Gwet’in–Tŝilhqot’in First Nations have been able to sustain much of their traditional lifestyle in a still-intact wild-horse ecosystem.

Since first being introduced by the Tŝilhqot’in about four centuries ago, the Chilcotin wild horse has been able to roam free and thrive within a fully functioning predator-prey ecosystem. Horses and other wildlife also benefitted from improved habitat that resulted from the Tŝilhqot’in’s carefully controlled burns. To the Tŝilhqot’in, the horse was a special being, Nen.

This wild-horse mare escaped a neck snare set up along a trail, though her neck is still scarred. Such snares sometimes kill horses and also catch and kill moose, deer, and other species. Image courtesy of Darrell Glover.

This stasis continued during the early fur-trade era, during the first half of the 1800s, but changed abruptly with the subsequent arrival of thousands of cattle during the Cariboo gold rush of 1858–1860. According to Thistle, cattle ranching arrived “just after Native populations had been decimated by smallpox and at a time when the government of British Columbia offered land for purchase or lease for next to nothing. Ranches and cattle quickly took over the grasslands and cattle competed there with other creatures the ranchers soon considered pests.”

Between 1859 and 1868, 21,216 cattle from the US were tallied crossing into the colony at the government’s Customs House at Osoyoos. These first bovines were a mix of British shorthorn and Spanish cattle that originally came from Mexico via California.

It was a long journey for the drovers to trail their large herds through the Okanagan grasslands following the well-established Indigenous and Hudson’s Bay fur brigade–Okanagan Trail to Fort Kamloops, then on to the Cariboo. After the gold rush waned in 1860, some of the cattlemen stayed and started cattle ranches. The carpets of pristine, knee-deep bunchgrass that cloaked the interior prairies and sagebrush hills were too hard to resist. Many new immigrants followed once the word was out that the colonial government was allowing the cheap pre-emption of the grasslands.

By 1863, the flood of immigrant settlers had rafted across the Fraser River into the remote Chilcotin grasslands. They poured into the Chilcotin from many foreign countries, in a steady trickle or in surges, using horses, wagons and pack horses to transport their families and possessions.

The Tl’esqox (Toosey) Horse Nation in the East Chilcotin were the most vulnerable and thus the first of the six Tŝilhqot’in groups to feel the brunt of the immigrant influx and have their traditional lands pre-empted for cattle ranches. The Tl’esqox (Toosey) were forced onto reserves too small for their herds of wild horses or to support their traditional subsistence lifestyle. Today, they still keep their own special herds of horses for teaching their youth equestrian skills and for cultural revival related to their deeply ingrained relationship to the horse.

Excerpted from The Wild Horses of the Chilcotin: Their History and Future by Wayne McCrory (Harbour Publishing, 2023). Reprinted with permission from the publisher. Read more Impact stories.