When Djavad Mowafaghian was a little boy, his mother said something that would stay with him for the rest of his life. She looked at him and said, “Djavad, I hope one day you will become a very rich and successful man. But when you do, never forget that your money comes from the people around you. When you have enough, send that money back to the original owners—the people.” Now, at 85 years old, he can proudly say that he has more than lived up to his mother’s hopes.

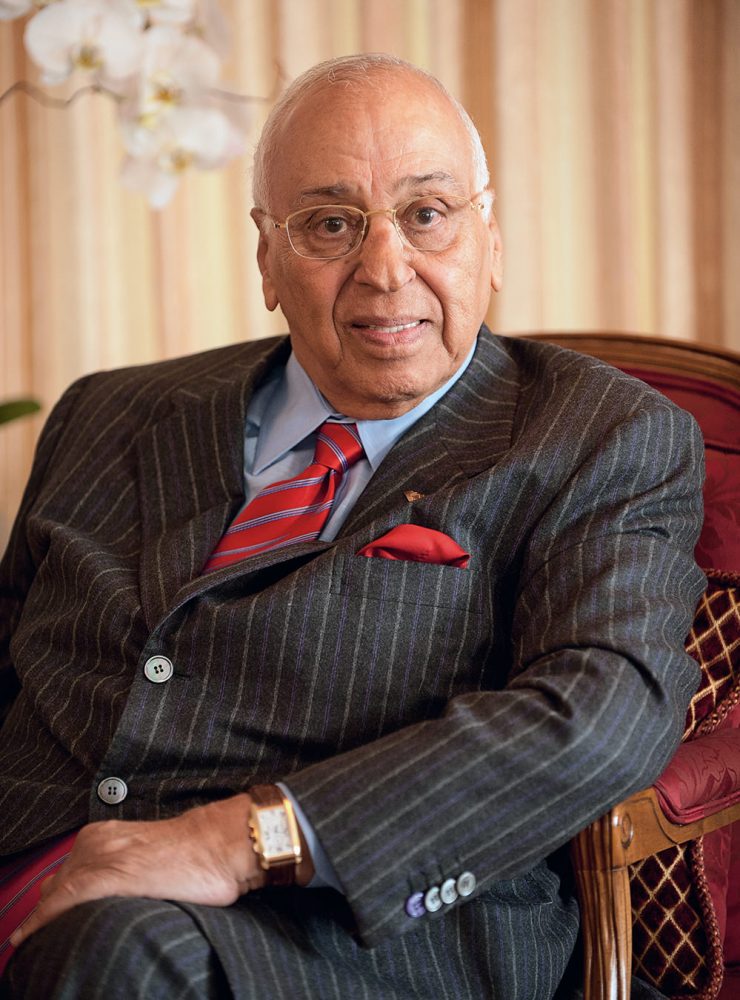

Mowafaghian is a distinguished man—silver hair, well groomed, and wearing a bow tie on this particular day as he is being interviewed at the North Vancouver offices that house the Djavad Mowafaghian Foundation. But to ask about the millions of dollars he has made and donated is not the quickest way to get to know him. Instead, simply look into his eyes, which tear up more than once as he speaks about his mother and the matters that are most important to him.

Growing up in Iran, he lost his father when he was one year old. Mowafaghian has little memory of him, except for the name his father left him: “Djavad”, which fittingly means “generous”. His mother raised her three children alone. “In those days we had no electricity and no heating—we used coal,” he says, speaking slowly in a deep, gravelly voice inflected with a gentle accent. “My mother would make bags of coal and gave them to the poor for winter. She was a generous lady, always preparing food, sometimes feeding others before her own children.” It was here, by daily example, that he saw the meaning of generosity. He carried this ethic of giving with him through his schooling and into his working life, where he established one of the largest general contracting companies in the country, building major housing developments, hospitals, factories, and roads.

Mowafaghian’s climb to success came with challenges. “When I was working, I became bankrupt two times,” he says matter-of-factly. “I suffered, sometimes even for food, but I never gave up. I never worried. I had courage and hope that I would come back again, and I did.”

Boy’s technical school in Karaj, Iran, built by the Djavad Mowafaghian Foundation.

As his success grew, so did his generosity. To date, he has built 26 elementary, middle, and technical schools in Iran, spanning a total of more than 800,000 square feet, which each year house and educate approximately 22,000 children in the poorest areas of Tehran. Several of the schools were built for girls and boys separately, while others catered to students with specific disabilities, such as visual and hearing impairment. Over time, these schools have had a massive impact by lessening crime, increasing safety, and instilling a sense of hope about the future.

In 1982, Mowafaghian moved from Iran to Geneva, Switzerland, but knew he would not stay long. After learning that a good friend from Iran had settled in Vancouver, he visited the city. “I hadn’t even heard the name of Vancouver before,” he says with a chuckle, remembering how quickly it felt like home. “I really liked the people. They were educated and happy, and always smiling. It felt safe and clean, and so in 1987 I decided to try my chances and come to Vancouver.”

The Djavad Mowafaghian Foundation in Vancouver was started in 2003, and to date has donated or committed more than $48-million to various charities in Greater Vancouver, including Simon Fraser University, the University of British Columbia, Vancouver General Hospital, B.C. Children’s Hospital, Lions Gate Hospital, and the Centre for Child Development.

“We built a Foundation because we have a vision. It’s not just about transferring money to others but about building something that we have invested in and believe in.”

In 2010, Mowafaghian suffered a stroke, and his mother’s advice came rushing back to him. “When I came out of the hospital, the first thing I decided was to transfer [all my assets] to the foundation,” he recalls. “I was very, very happy with my decision.” Among his first donations after the stroke were to the VGH & UBC Hospital Foundation, to support causes personal to him: a new neurosciences unit, the British Columbia Centre for Stroke and Cerebrovascular Diseases, and the Centre for Brain Health. “The health and education of children—regardless of nationality, race, and faith—is my mantra. The initiatives at UBC are covering my mantra as well as brain health, which has been my personal problem since having a stroke.”

A quick glance around Mowafaghian’s office makes evident the impact that he has had on others. Photos adorn the walls and the top of his desk. Books, pages of poetry (a few in Braille from a blind boy in Iran), cards, and letters are stacked on his shelves—all written by inspired children, grateful parents, and passionate researchers. He plucks a photo from the table and recounts every detail of this child’s struggle, his eyes softening with tears and his voice catching in his throat. “This is the life,” he says, explaining how others have impacted him through their acts of love and gratitude. “Giving is the essence of life.”

His nephew, Hamid Eshghi, president of the Mowafaghian Foundation, takes over the conversation. “We built a foundation because we have a vision,” he says. “It’s not just about transferring money to others, but about building something that we have invested in and believe in. My uncle does not want to simply transfer money to the next generation, but also his knowledge, his ideas, his philosophies about health, education, and being a good person.” Knowing where and how each dollar is being spent is very important to Mowafaghian, and the foundation follows a strict process. “Sometimes it takes two years to reach the agreement to invest,” says Eshghi. “Once we begin the project, we visit the site regularly and follow up with the promises we have made.”

The goal for Mowafaghian now is to live simply. “My children and grandchildren are all happy and healthy, and I am also very happy,” he says. As for creating a legacy, all he hopes is that he has passed on to his young grandchildren the same ethic of generosity that his mother passed onto him.