What confers classic status on a literary text? I consider a work classic that takes up permanent residence in my imagination where I can and must revisit it. We can only properly reread a classic, accumulating meanings, adding to what it tells us an increasing awareness of how it tells us, how it uses and renews the conventions of literature and the resources of language.

For me, a book lives and earns its afterlife through its handling of language. Even its characters, also crucial, come convincingly and compellingly alive through the language of their presentation: the words, their connotations and nuances of meaning, the sentence structures and rhythms, and the images that detonate in our minds and imaginations.

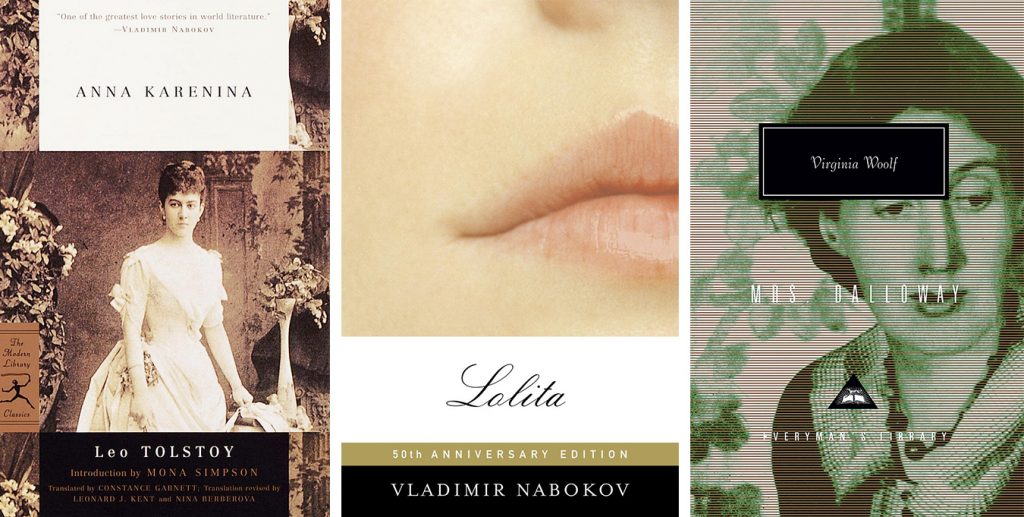

Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina is an undisputed classic, a supreme example of the vast 19th-century novels whose scope could capture the fullness of personal and social life. Much of its effectiveness, however, lies in its techniques: the double romantic triangles, the recurring motifs, the dream sequences, and one of the earliest uses in fiction of interior monologue to mine psychological depths.

But the novel’s life force is Tolstoy’s rendering of Anna, which transcends cultural distance and translation. Neither an innocent victim nor a naive dreamer, Anna is a mature, sophisticated woman of the world with social position, prominent husband, loved child. She entrances us, from the play of her features and thoughts on her first meeting with Vronsky at the train station to the depth of her competing love and anguish at the very moment she and Vronsky consummate their affair and she fully grasps the implications of her actions, a realization that ultimately overwhelms her.

Nothing might seem further from Tolstoy’s densely populated, expansive world than the confined spaces of Virginia Woolf’s Mrs. Dalloway, a single day in London, in June 1923, and for the most part in Clarissa Dalloway’s upper-middle-class home, yet its main action—Clarissa’s planning, then hosting a social gathering—incorporates a comparable range of issues.

Woolf’s prose is supple and fluid enough to convey a sense of life as a continuous stream of activity and sense perceptions, of objective facts and subjective responses to them. Her stylistic alchemy transmutes the ordinary into the extraordinary, giving domestic objects and incidents wide symbolic range. She takes what was already a poetic cliché, a window as a dual mode of perception, outward to the world and inward to the soul, and charges it with new force and strategic placement. The novel begins with Clarissa’s memory of the soaring spirit of her younger self throwing open a window to plunge into life, but it will be a literal and deliberate plunge from a window that ends the life of Clarissa’s counterpart in the novel, Septimus Smith, a traumatized veteran of WW I who has lost the capacity to respond to life but who resists society’s efforts to re-engineer him as a socially useful tool. Clarissa and Septimus never meet, though news of his death that day intrudes into her party, and the climax of the novel is her response to it, framed within another pair of windows. Regarded by her friends as a snob who gives parties to further her husband’s public-service career, Clarissa actually has a more substantial purpose. Her parties are careful compositions whose medium is people and whose goal is harmony and unity, a momentary stay against the disintegrative forces of life.

Like Woolf, Vladimir Nabokov insists on the absolute integrity of every entity, and no other novelist I know of pays such loving attention to the precise and minute details of our world, human and natural. His infamous novel Lolita, supposedly a salacious potboiler offering itself as an unedited prison memoir, is one of the most intricately structured and richly allusive novels we might ever read.

Language as blatantly central and seductive is obvious from the start, not the protagonist Humbert’s rhapsodic introduction of the heroine’s name but the savagely satirical forward by John Ray, Jr., itself part of the novel. The wordplay, puns, anagrams, unlikely names, repetitions and coincidences indicate that contrivance and constructs of various kinds are at issue. Indeed, rarely do we glimpse the real Dolores Haze; instead we see only Humbert’s rendition of her as his Lolita.

Nabokov sets himself a daunting task, situating the reader in the consciousness of a pedophile and murderer, but—and here’s the key—he situates Humbert fully in Western culture’s cult of love. He takes us on a pair of wild journeys by car through all of the then 48 United States, first with Humbert on the run with Lolita, then again with Humbert in pursuit of Lolita and his shady alter-ego Quilty. And he also takes us on a cultural journey, from Petrarch and Dante to pop culture, indicting a tradition that makes a person, usually female, into an object of another’s obsession, possession, and use. Often hilarious, even farcical at times, this novel is profoundly moving, deeply moral, and endlessly provocative.

Provocation is appropriate. Classics redeem the complexity and intransigence of reality: they challenge us, unsettle our assumptions, even our previous interpretations. Must Anna die? Are Clarissa’s radiant moments enough compensation? Is Humbert’s remorse at the end of the novel convincing? Lingering questions send us back into the worlds of the novels, knowing we will emerge with fuller comprehension and even greater pleasure.