Brad Phillips has a reputation.

He makes text-based art and photorealistic paintings of still lifes—things like flowers stuffed into toilet paper rolls, and portraits, lately of his wife, partially nude and often bound. He also writes, and produces photographs and video. He is known to be sardonic and talented.

In his writing, Phillips denies being a genius, accepts he’s an “asshole,” and talks about being a former junkie in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. In his criticism, he isn’t shy to call the work of other artists derivative or twee. He has been known to snarl and toss vitriol at acquaintances greeting him in the street. “I’ve done a lot of bad things. I’ve been a very bad husband and a bad son, broken the law, and been a miserable friend and a bad person,” says Phillips. “I have a lot of work to do before I become a loveable person.”

All of this seems at odds with the soft-spoken 43-year-old currently sitting in a Toronto cafe. Wearing a colourful Madras plaid button-down over a faded Boston Celtics shirt that he’s had since Grade 9, and vibrant hand-embroidered Berber slippers from a Moroccan goods shop, Phillips discusses his cult of personality. It’s the reason he and his current wife, artist Cristine Brache, had to get a P.O. Box—a decision made after an admirer mailed Phillips her high school diaries to their home address. It’s also the reason he made his Instagram account private—to keep his more than 33,000 followers from growing, and to stem the flow of direct messages.

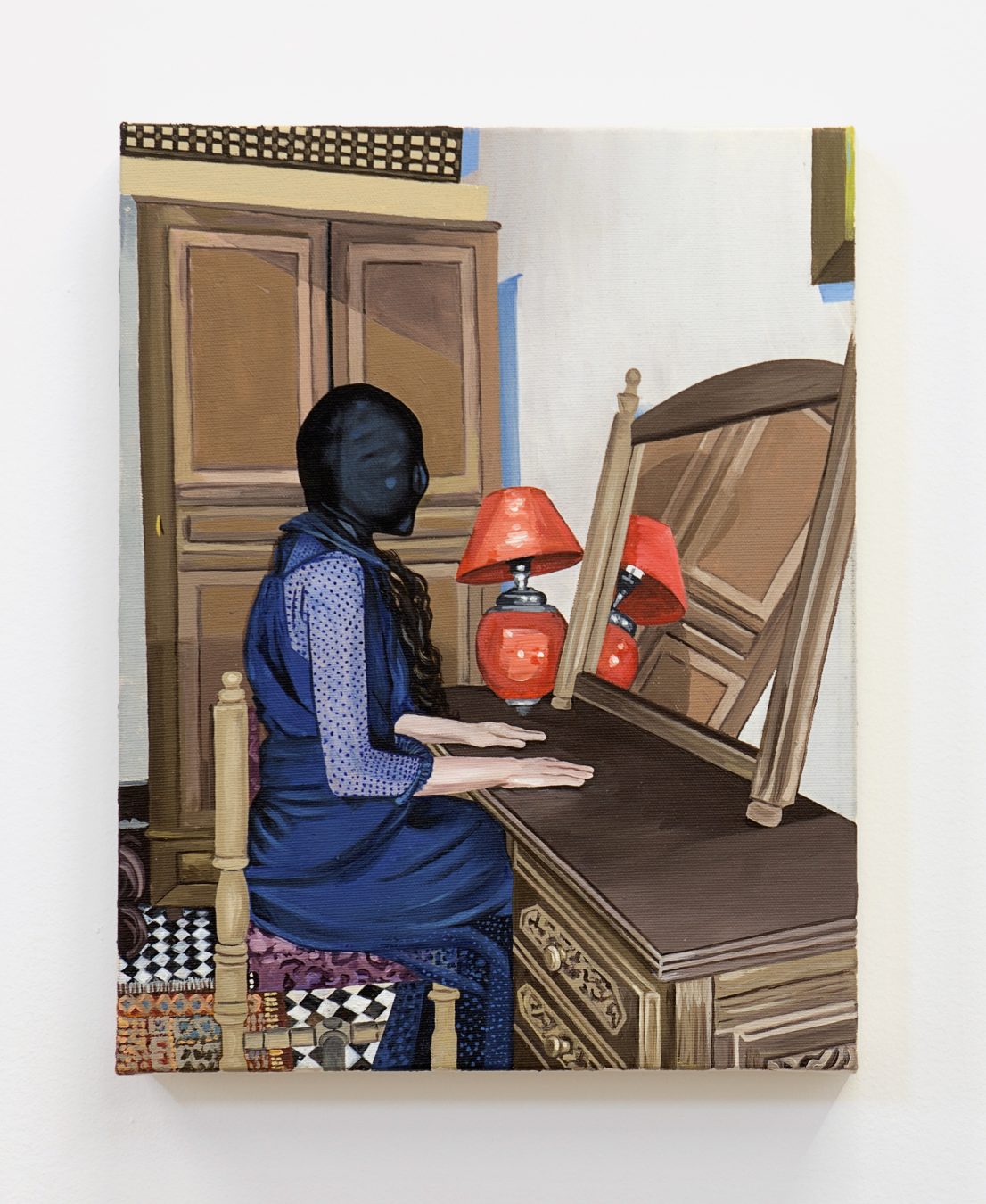

He hears from both fans and detractors often. Phillips thinks the reason people seem so eager to contact him is because of the autobiographical nature of his work. The irony is that he tackles taboo subjects, like drug and sex addiction, as a way to reach out. In one painting, Brache is seated at a dressing table facing its mirror. Her head is covered by a black bondage hood. She wears a chaste navy Swiss dot dress, its three quarter-length sleeves covering her arms, which are bent 90 degrees at the elbow with her forearms and hands resting flat across the vanity’s surface in perfect finishing school posture. An orange lamp sits on the dresser, shade slightly askew, and a large wooden wardrobe stands in the background.

All of his visual work is a precursor to his literary career, which Phillips is now focusing on. “To me it’s all part of the same project,” he says of his output. And this new body of work tackles the same subjects: intimacy and vice, ego and self-depravity. “I write these things because I genuinely want to connect with other people. I want to be able to make myself vulnerable, to write about things that are shameful, to take on that burden so they can read it and feel less alone,” says Phillips, who is currently working on a book of short stories and a collection of essays. “But I still don’t want them to contact me.”

Once, he responded to a letter only to later on find his reply up for auction on eBay. This sort of thing bothers Phillips; he sees it as people profiting off of his name while he remains broke. “My work doesn’t really sell very well, but people really like it,” reveals Phillips.” It’s confusing and frustrating and kind of humiliating.” Still, it’s not clear whether financial success would make him immune to the things people say about him. “It hurts to be told you’re a sexist or you’re an asshole,” he admits. “But if someone was critical of my actual work, if I got a bad review or someone said, ‘This writing wasn’t very good,’ that’s okay. It just doesn’t happen.”