Clarity. If I had one word to define my impression of 1972’s Easter Be-In, that would be it. In a low-probability scenario for early April in Vancouver, the sun came out warmly, and thousands of people converged on the Prospect Point picnic site in Stanley Park. The colours of the day seemed enhanced (not from any mind-altering substances, at least in my case!): the skies were crystalline blue, the field and trees were saturated greens, and the crowd scenes were punctuated by yellow daffodils carried by some of the “flower children.” The air had a sharp spring quality, mixed with the smell of the saltwater and forest nearby. The images and sensations of the day are logged in my memory banks with perfect precision.

The Be-Ins took place from 1967 to the mid-1970s in Vancouver, in various locations around Stanley Park. Set in an amphitheatre of Douglas firs and cedars, the free outdoor concerts, in mini-Woodstock fashion, still had a uniquely West Coast vibe. The Prospect Point picnic site, with no neighbours nearby to be impacted by the sound, was ideal for the 1972 event; the field was filled with people.

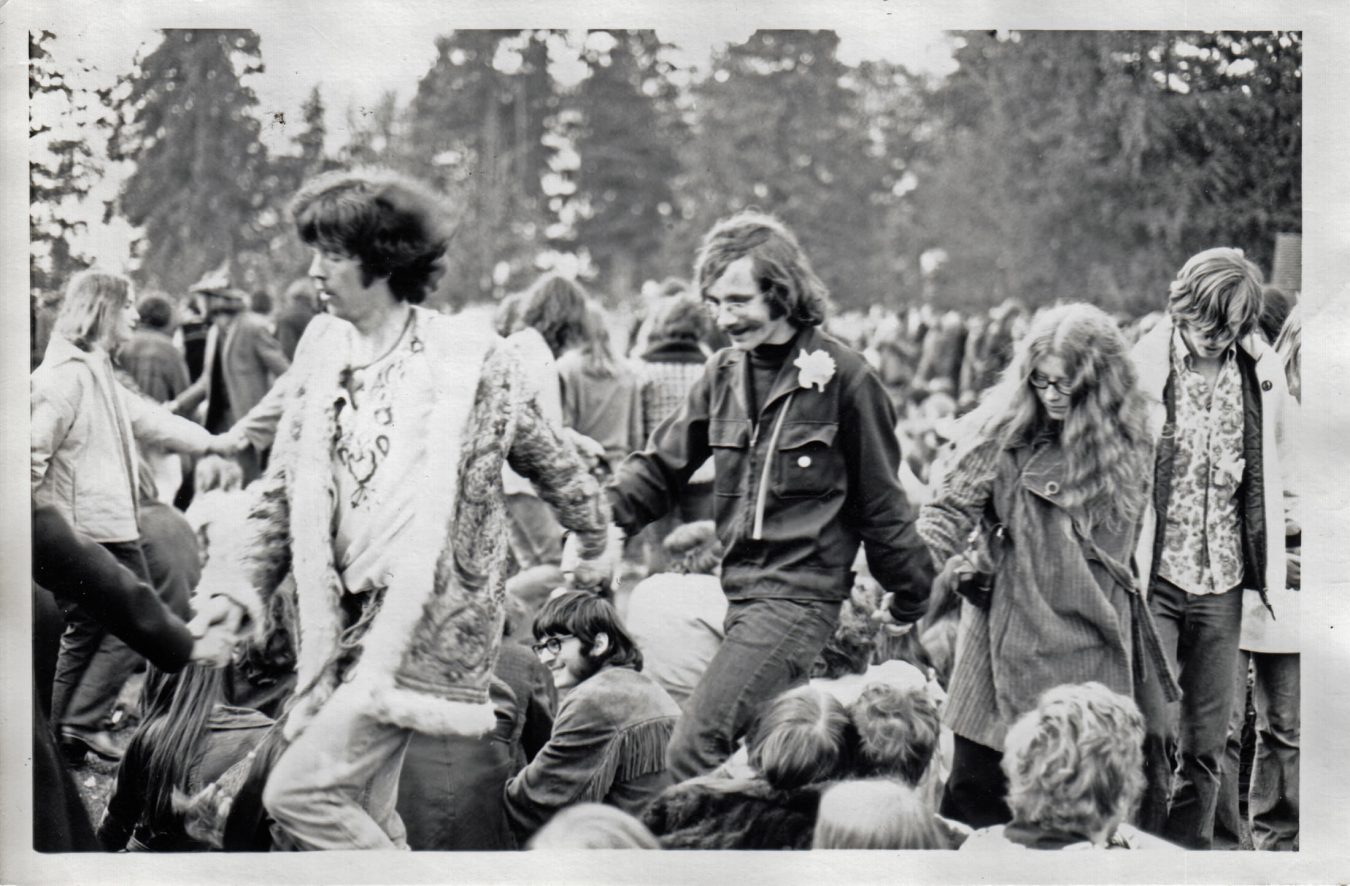

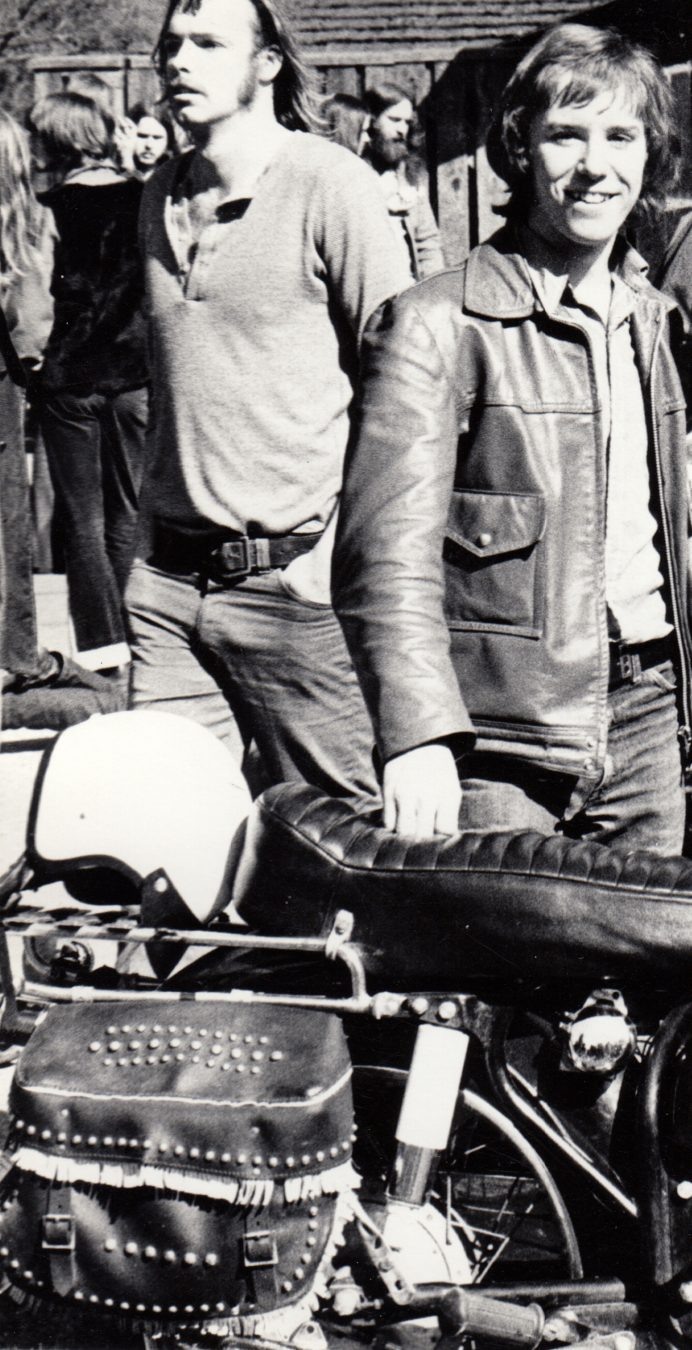

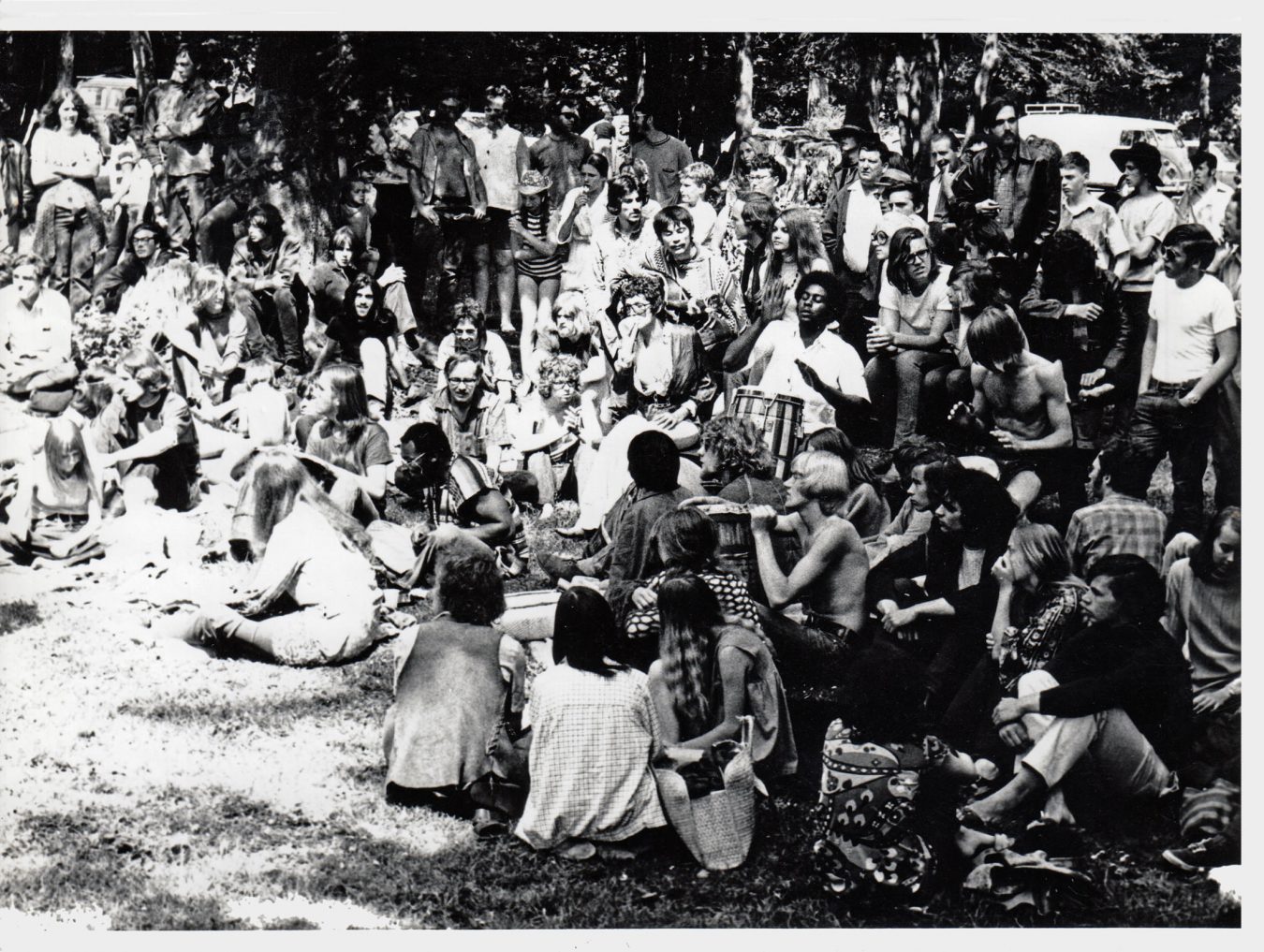

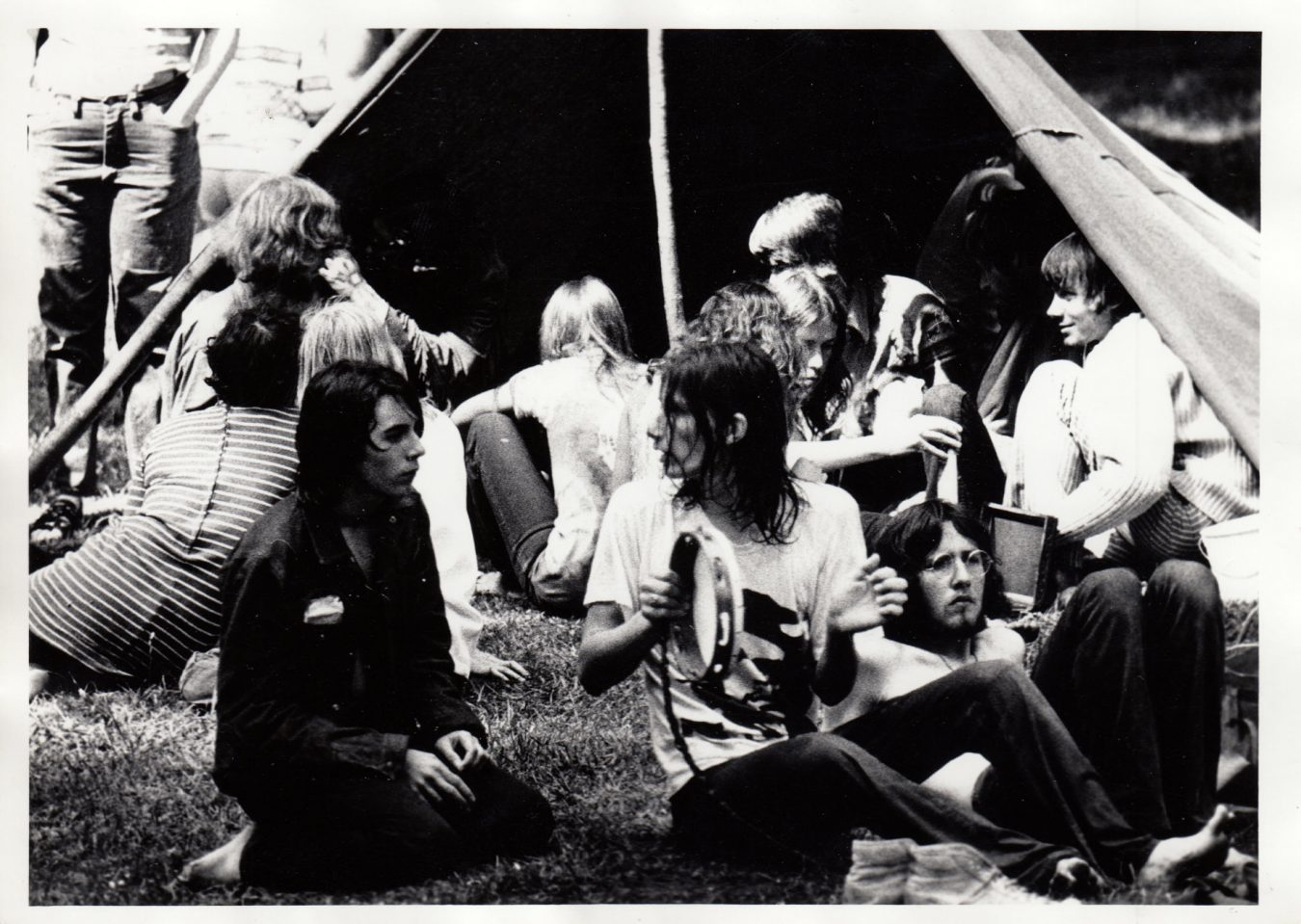

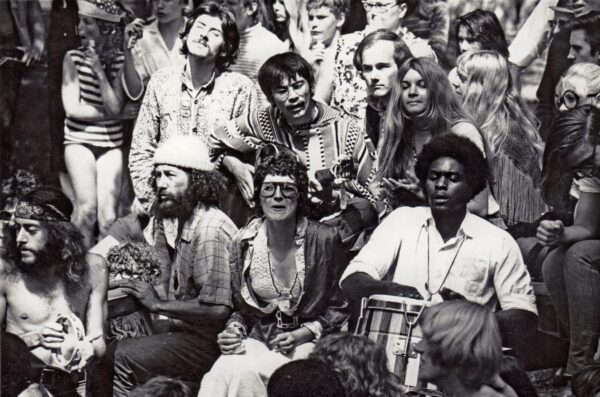

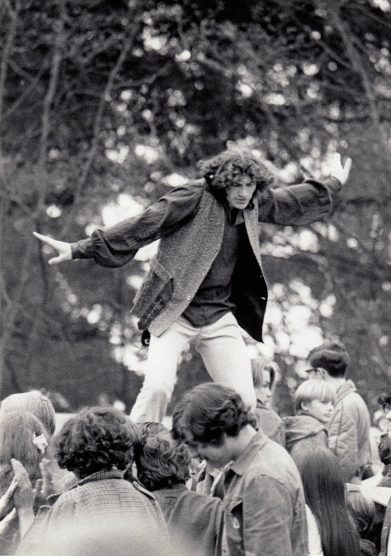

The concert felt like part of a great adventure, and had a feeling of oneness and community, bringing together every subculture faction of local youth: hippies, students, bikers, musicians, poets, and the rest. Many people could be seen in quiet contemplation, focusing on the smell of a daffodil or meditating. Others danced alone, or in a line snaking through the crowd.

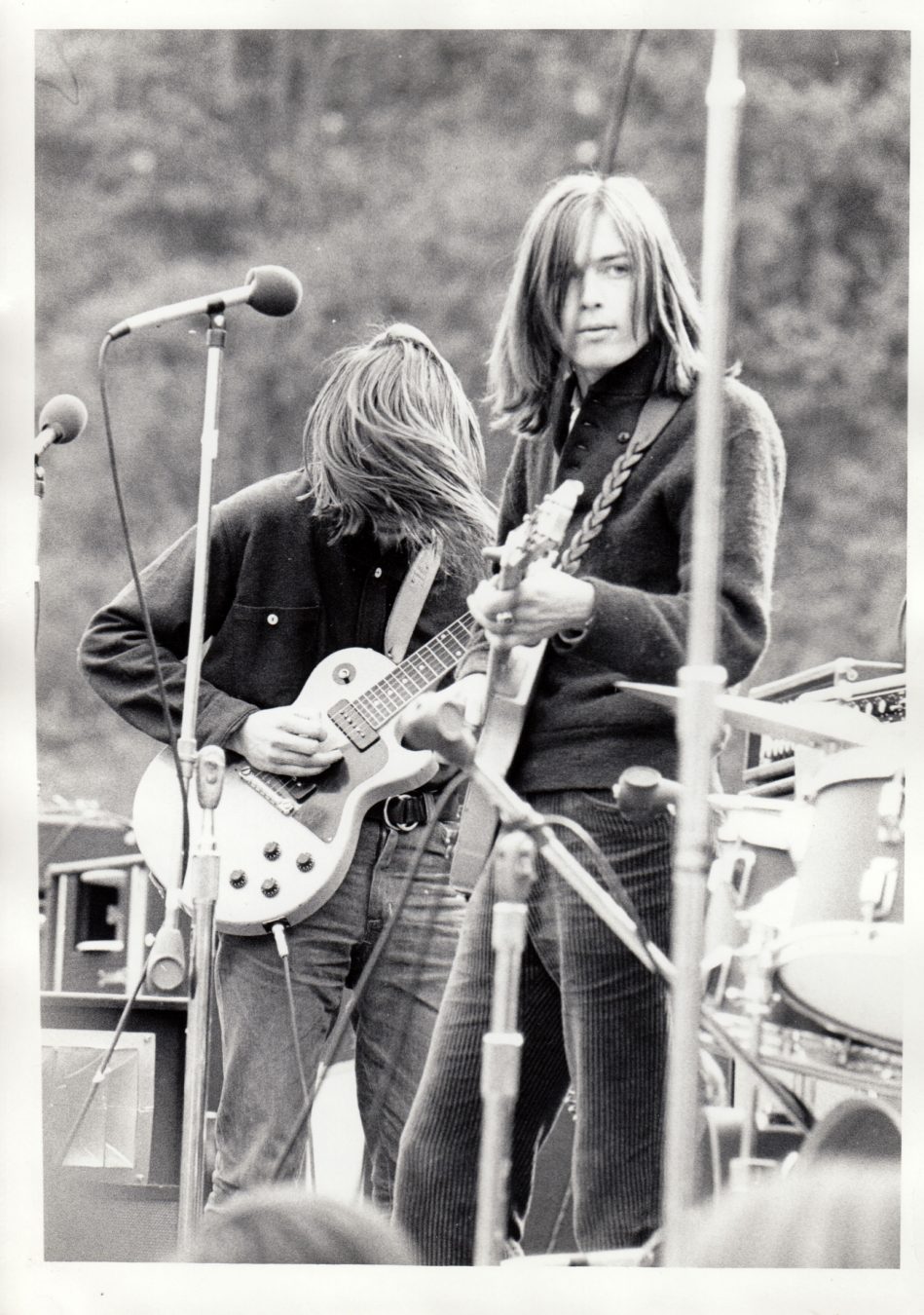

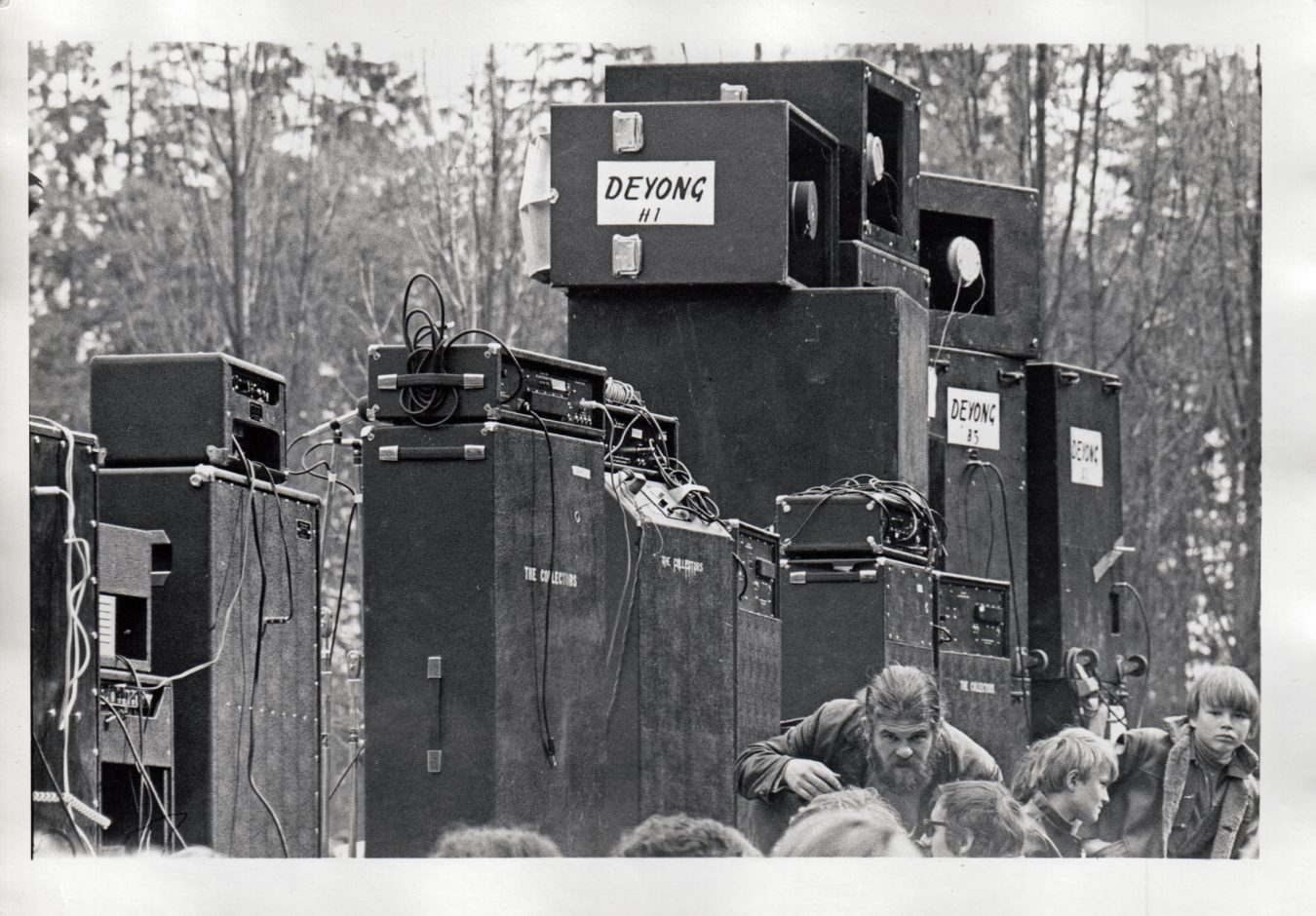

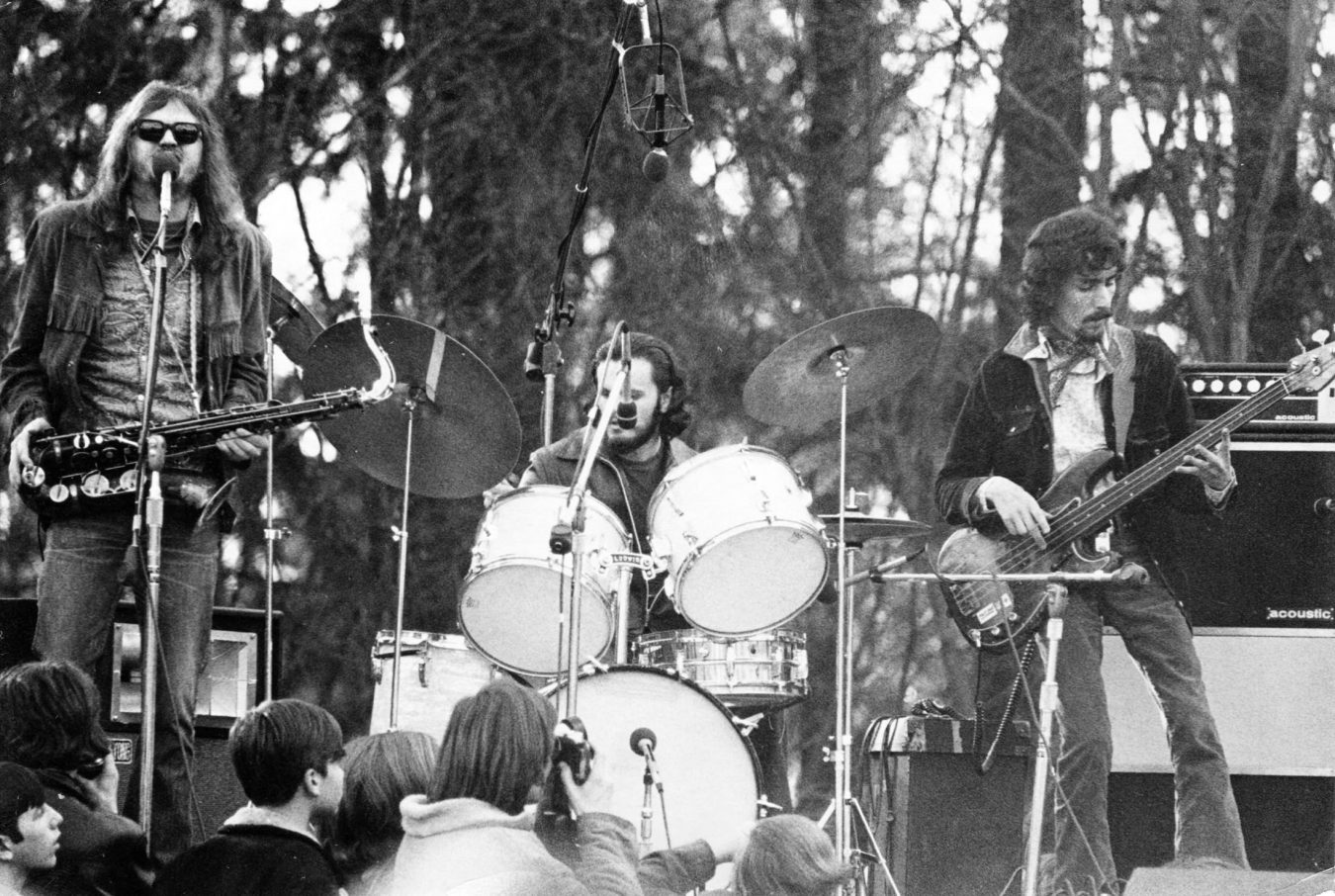

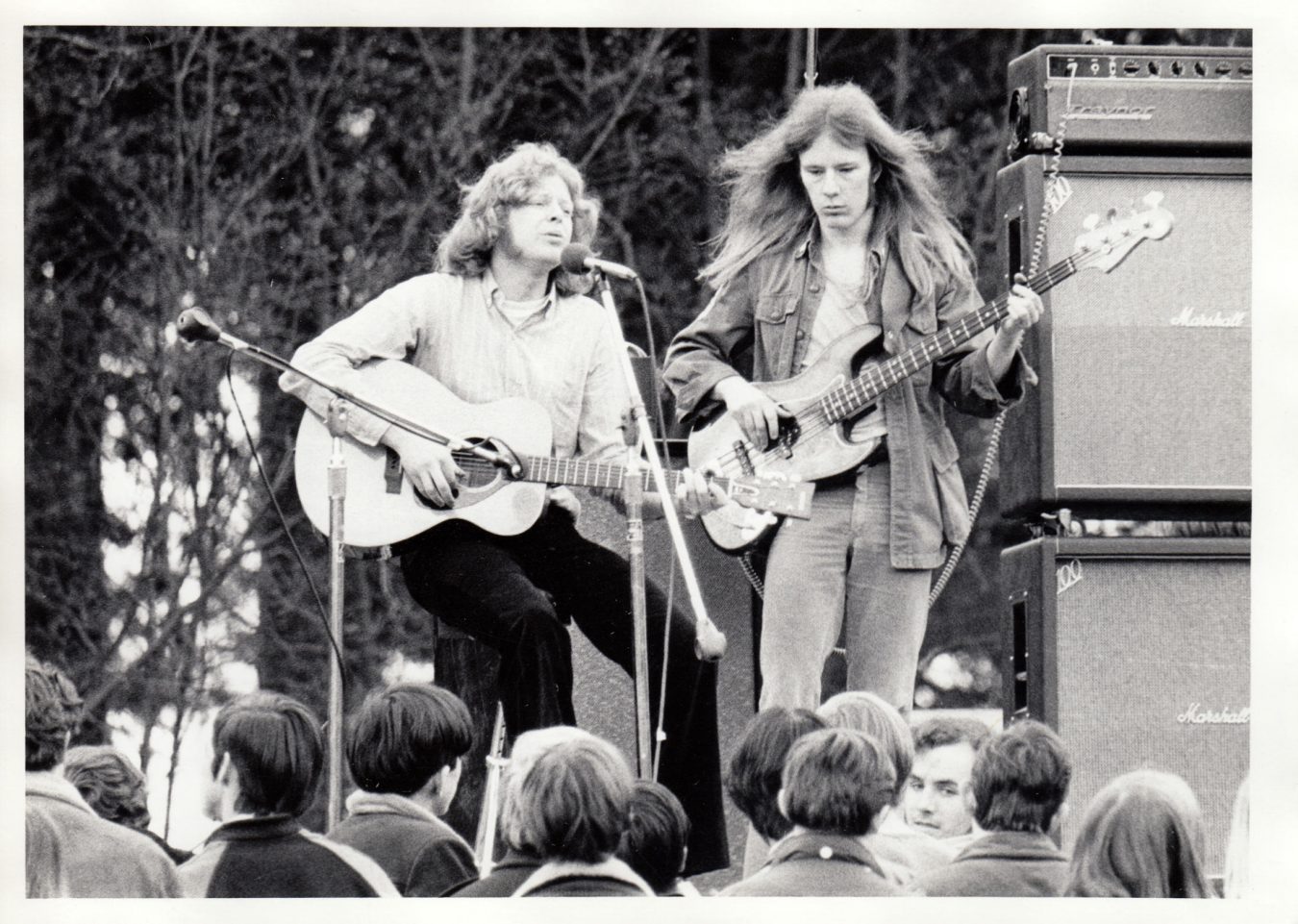

On the main stage, a wall of amplifiers projected a gut-thumping sound to the large open space, and top local bands such as the Collectors performed before the multitude. Some distance from there, smaller groups performed on bongo drums and tambourines, setting up a rhythmic counterpoint to the headliners, and drawing a crowd within their own sphere of influence.

I was 19 years old, taking a break from second-year UBC engineering final exams, and no doubt I thought that taking in the music at the Be-In would be better for my body, mind, spirit, and test performance than a few more hours of cramming. I decided, probably like many others, to attend on a whim because the weather was so beautiful.

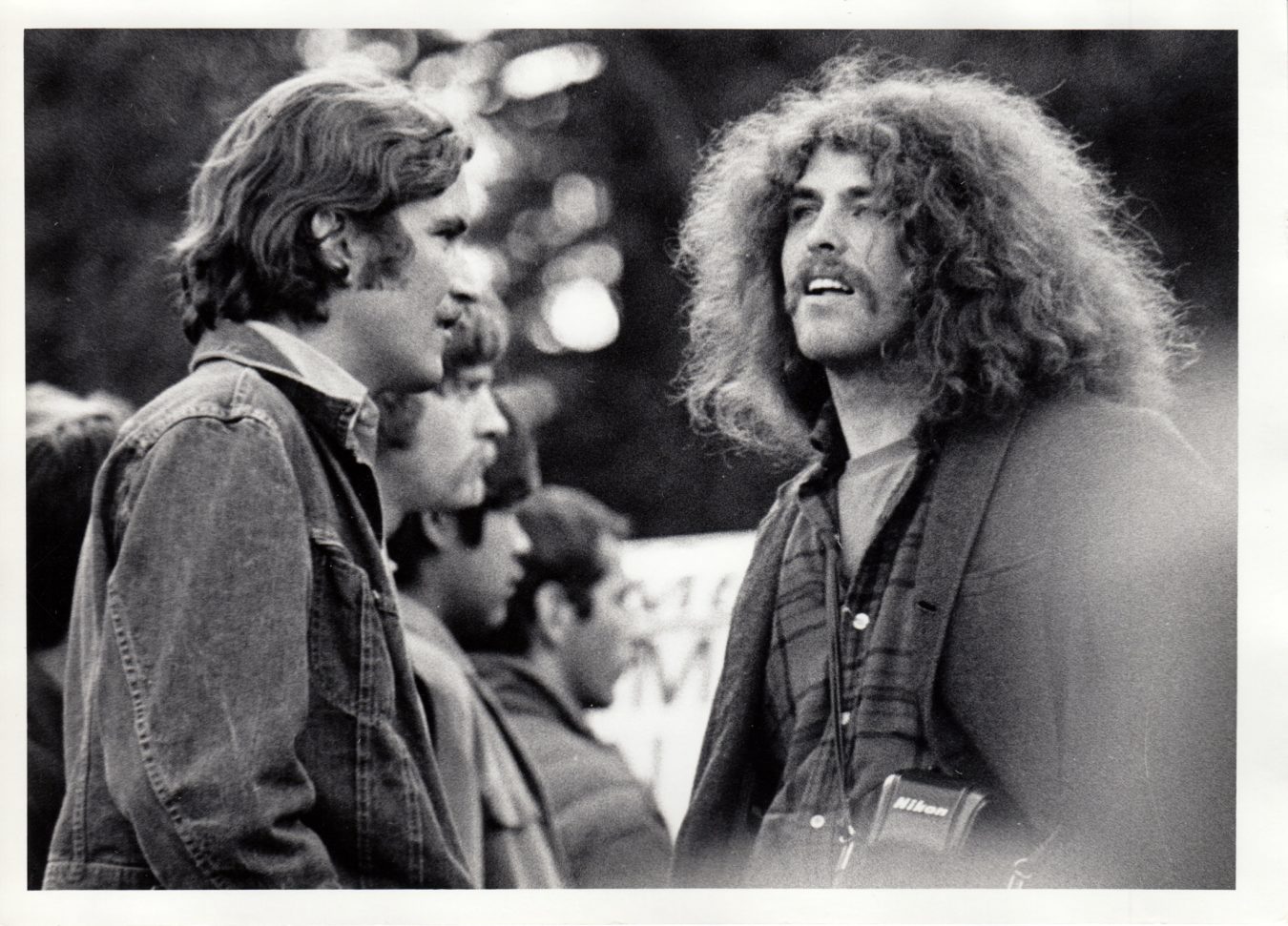

I had been an avid photographer since age 11 or so, when I was given my first camera. I was further inspired to pursue the art by Fraserview’s David Thompson High School photography club teacher, Mr. Ikuta, and learned the darkroom craft in the school’s graphics department. I shot the team, group, event, and candid photos for the school yearbook, and in Grade 12, took an outside course at Vancouver Community College, where the instructor encouraged me to find photographic opportunities everywhere—especially in street photography. The mindset of always looking for compelling human-interest situations is what made me decide to take my camera to the Be-In. I photographed that day with my workhorse Pentax Spotmatic 35-millimetre, with most of the images taken through a 200-millimetre telephoto lens. The film was processed in my darkroom at home.

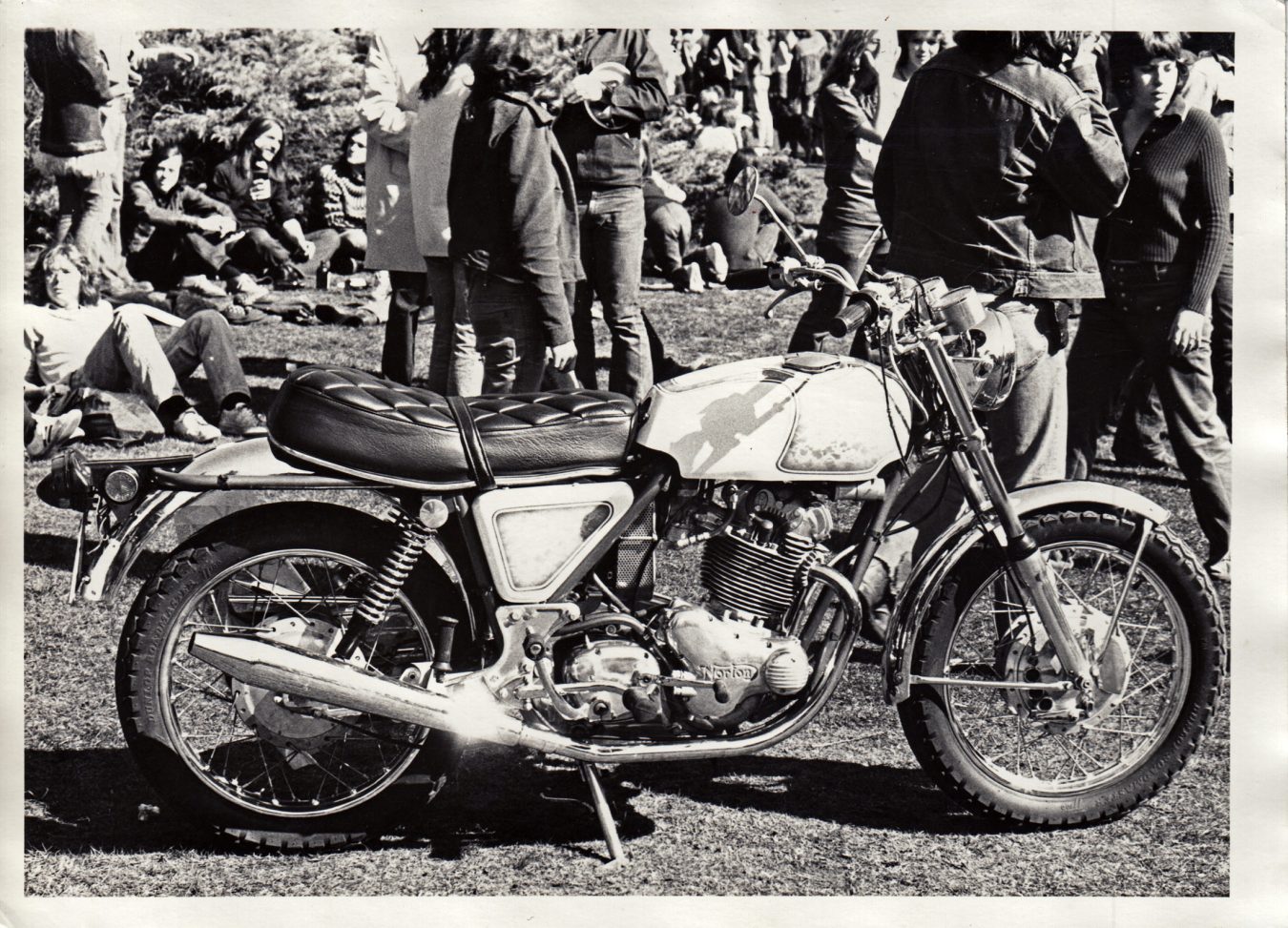

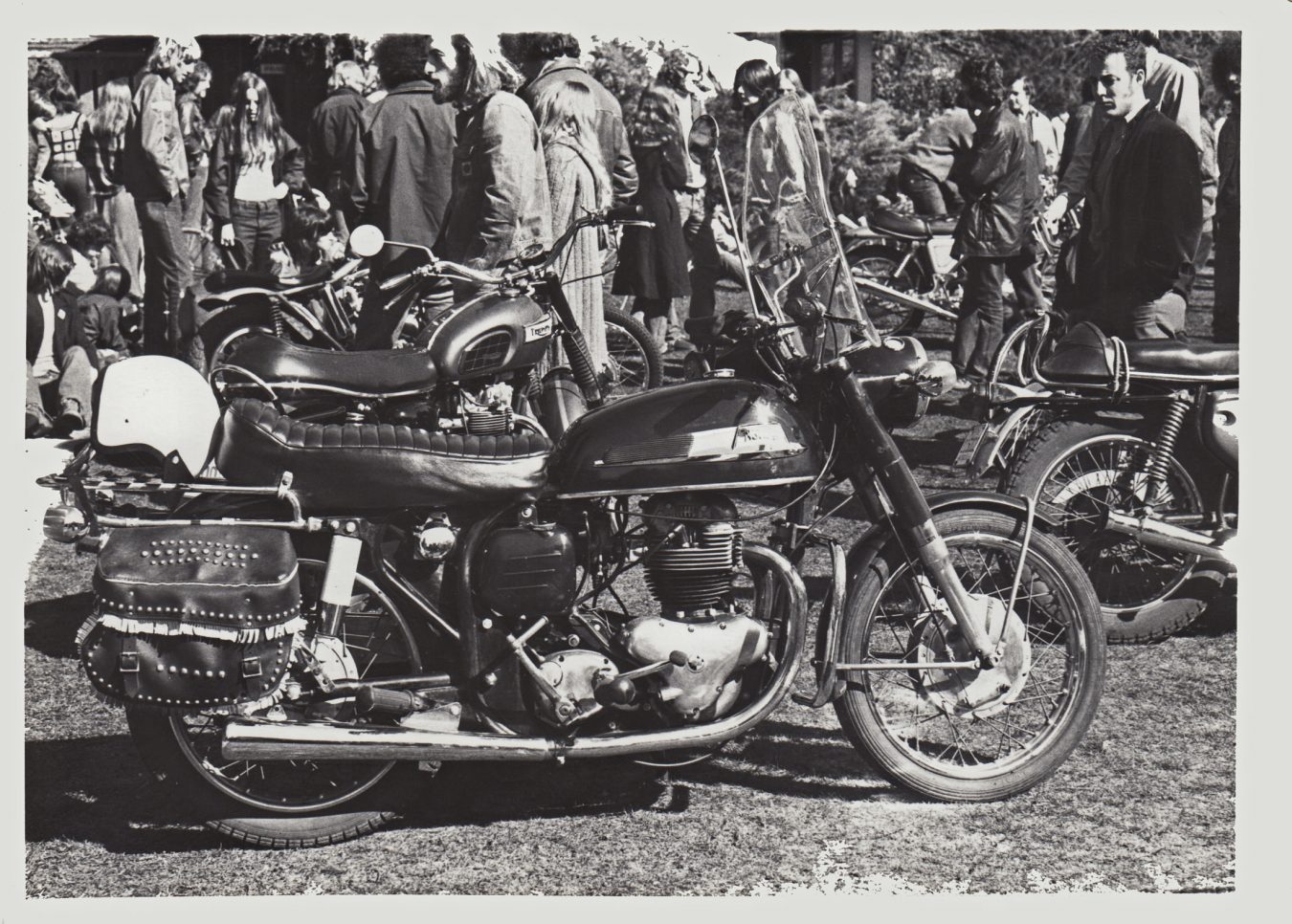

One of my favourite photography subjects at the time was motorcycles, and I drove to the event on my own 1961 Norton 500 Dominator. It had been modified with high-compression pistons and a Dunstall tuned megaphone exhaust system. The sound it made was a distinctive rumble, and it resonated in my head as I rode through the park to the event, presaging the rhythmic drumming at the concert. (Digression: Japanese motorcycles were on the ascendency then, being more reliable, leaking less oil, and having higher performance than the British bikes, but in my opinion, they never equalled the sound or looks of the English versions; that, however, is the topic of another story.) The motorcycles were all parked on the grass at the concert site, in a kind of Easter Sunday parade of the marques of the day: Triumphs, BSAs, Nortons, Harleys, and yes, some Hondas and Suzukis. Parked a short distance away were the more eco-friendly 10-speed bicycles.

Vancouver’s first Be-In followed in the footsteps of a similar event, the Human Be-In, held in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park prior to the Summer of Love. Like San Francisco for the States, Vancouver was on the leading edge of Canada’s counterculture in the mid-to-late 1960s, with its favourable climate attracting many hippies and hitchhikers who came from across the country for the openness and adventure here. With the benefit of a rear-view mirror on history, I see the 1972 Easter Be-In as having evolved to more of a mainstream youth culture event than a counterculture one. While there were still people in 1972 sporting long locks, unknown to those enjoying the event that day, the hippie age was past its apogee. Within a couple of years, the disco era was in full swing, perhaps as the Baby Boomers were finishing their education and entering the workforce. The photos of the 1972 crowd show the hippie garb of the 1960s largely gone.

We are blessed with an incredible natural and urban environment, and the joy of music with public gatherings held in outdoor spaces is now an accepted part of our culture. As I write this in May 2017, I am watching bands perform at David Lam Park after the BMO Half Marathon. Of course, there are many other outdoor events here, like the Jazz Festival and the Folk Festival, and I can’t help but wonder how much of this style of event has its roots in the Be-Ins. (Though Stanley Park always had a wonderful connection with outdoor performances through the Malkin Bowl, built in 1934.)

These days, when I ride my mountain bike through Stanley Park, I sometimes stop at the Prospect Point picnic ground, close my eyes, and imagine that fine spring day in 1972. I can almost hear the echoes of the bands, and sense the harmony within the gathering. For a moment again, I feel the clarity.

Keep building your Community.