“How do you create a culture of making the art the most important thing in the room?” This has been a key question for Emily Molnar since her first day as Ballet BC’s artistic director. She has tackled it practically through reforms in how the company operates, and also more philosophically in the cooperative atmosphere she has fostered in-studio with the dancers.

From that shared commitment to the art itself, Molnar has developed a company that dances as one force of energy and expression, able to bring to life the nuances of each particular movement while remaining fully engaged with the larger group dynamics. During intermission, local audiences tend to rave about the performers, and only after turn their attention to the choreography. On Ballet BC’s recent tour to England, including two sold-out shows at London’s prestigious Sadler’s Wells theatre, one seasoned British critic described the “confidence” of the dancers as “exhilarating.”

This popularity, and a sense of optimism and openness around and within the company, has grown over Molnar’s thoughtful 10 years at the helm. Within the organization, dancers’ salaries, for instance, are now based not on individual negotiations, but on years of experience through an equal and transparent matrix. “Different people rise to the occasion or want to participate in different ways,” she says, explaining that participation in making a work is as significant as performing it. “There’s no role that’s not important.”

For Vancouverites, Molnar’s leadership has refreshed the experience of ballet, showing what “contemporary” can be: relevant to people today, as fresh and athletic as it is technically virtuosic and styled. Molnar’s Ballet BC can be cool and postmodern, but it can also be emotionally engaging. That vision has been invigorating the national and international scenes, too, as the company’s touring commitments have steadily increased both in Canada and abroad.

Molnar and her artistic assistant work out of a small, bright nest of rooms on the seventh floor of downtown Vancouver’s Scotiabank Dance Centre, a couple of levels above the studio where the dancers rehearse (administrative offices are located separately). When she sits down to talk, Molnar begins by remembering one of her first acts as Ballet BC’s artistic director: brainstorming with the dancers about how to go forward with a shared vision. It was a bold way to launch the changing of the guard—one that stressed values of trust, support, and collaboration.

The fact that it took place in a boardroom, instead of sprawled on the floor in the more familiar studio environment, was significant. It meant they sat as equals around a table, where the baggage of ballet hierarchy—in which dancers have traditionally not been encouraged to speak up—could be more easily left behind.

At the time, the company was reeling from near bankruptcy, layoffs, and former artistic director John Alleyne’s sudden departure with his public dispute over severance pay. Saskatchewan-born, then-35-year-old Molnar had been quickly brought in as interim director.

“There’s no role that’s not important.”

The decision made sense. Molnar knew Ballet BC intimately; for five years, she had been one of the company’s most popular dancers, earning accolades for leading roles in Alleyne’s big story ballets. The character of Puck in The Faerie Queen was a standout: instead of the typically small male sprite, Molnar gave us a tall (she’s five-foot-eleven), regal, and very independent female force of nature.

After leaving Ballet BC in 2003, she remained in the community and launched a freelance career as a choreographer. Early attempts at finding her own creative voice, often performed on small Vancouver stages, led to major commissions, including the London premiere of Six Fold Illuminate in 2008 for Christopher Wheeldon’s high-profile Morphoses group. It was an exciting accomplishment for any choreographer, but particularly for a woman in a position that men ruled; only in present day, hot on the heels of #MeToo, is there a concerted effort in the dance world to think about why programs featuring all-male choreographers remain so common on ballet stages.

Ballet BC has been touring a triple bill featuring works by Vancouver’s Crystal Pite, Israel’s Sharon Eyal, and Molnar since 2016; that it features all female choreographers has earned a lot of positive comment. But she chose them for their ideas, Molnar asserts, praising her colleagues’ “incredible sense of craft.”

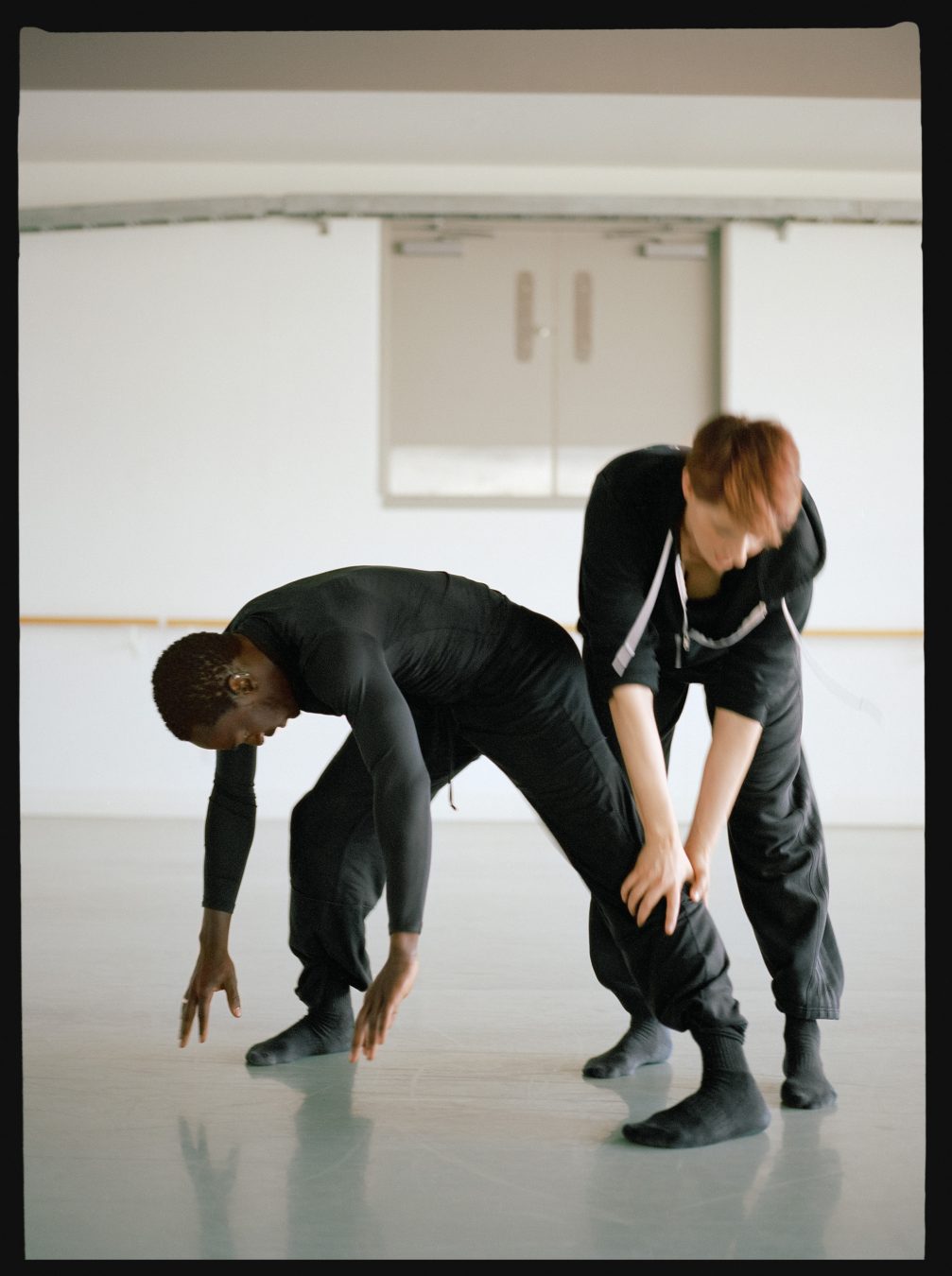

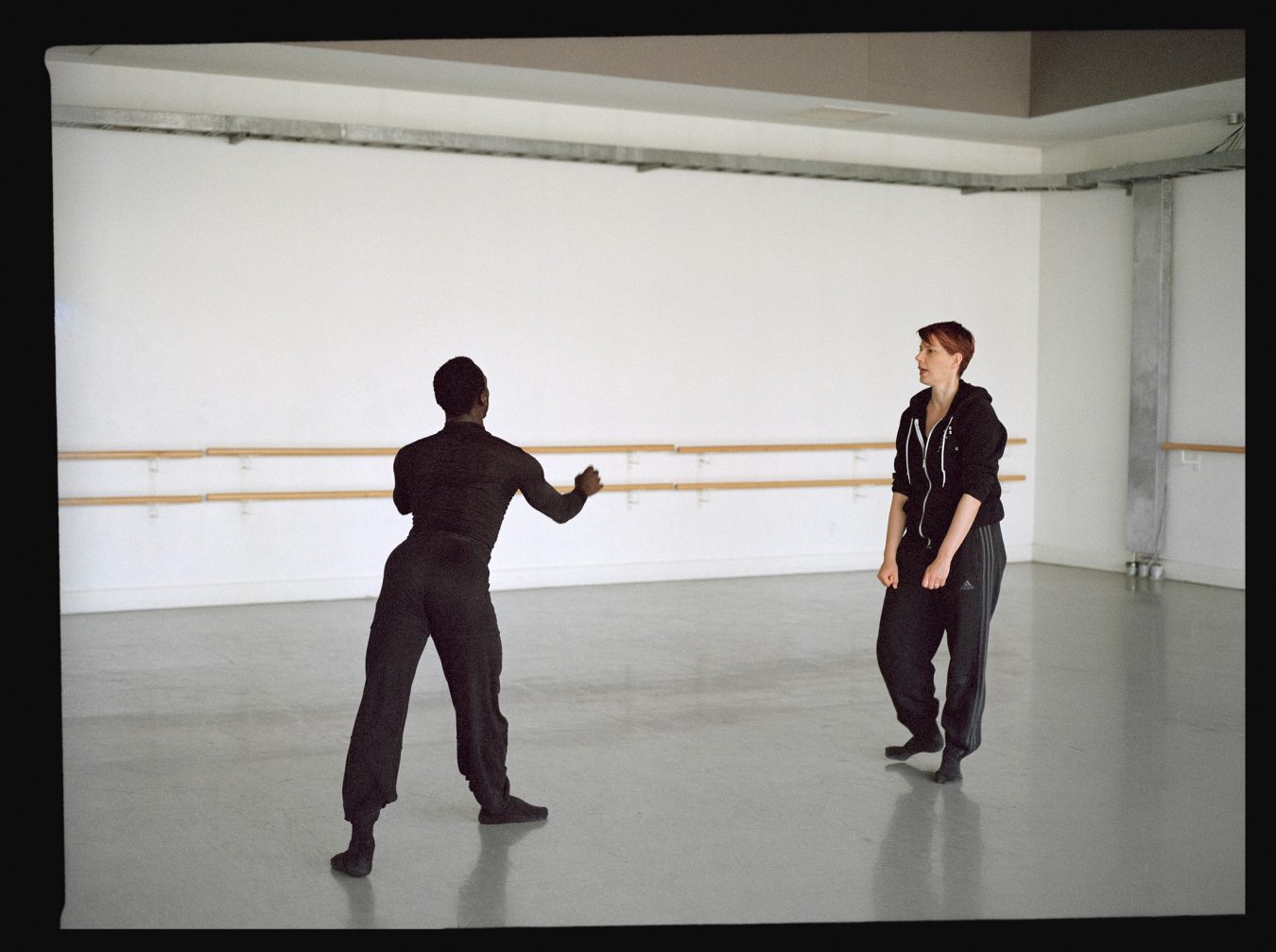

The company’s 2018 season begins in November at the Queen Elizabeth Theatre; the program also marks Molnar’s 10-year anniversary season as artistic director and will premiere her latest work. Of the more than 45 new pieces created for Ballet BC so far over her watch, Molnar has managed to include a debut of her own every year. It’s hard to squeeze in the time to choreograph, given all her other responsibilities—but in the studio with her dancers, the intimate and exposing moments of collaboration offer her a “high” like nothing else. “I learn things through that process,” she says, “I wouldn’t any other way.”

Molnar has long been drawn to creative exploration. It led her to leave the first company she danced with (the National Ballet of Canada) to be part of the Frankfurt Ballet, then under the direction of William Forsythe—widely acknowledged for hauling ballet out of the 19th century and into the future. She was just 21 years old at the time, thrilled to find her way within an environment of creative experimentation and independence.

Molnar’s enthusiasm for Forsythe’s choreography remains vivid even now. “Here’s a man who comes from a classical background, specifically Balanchine, who is today making these incredible site-specific works in galleries,” she says. “And everything in between.” His palette, she explains, is huge, containing both contemporary and classical ideas and form: “He doesn’t let go of one to hold the other.” While with Frankfurt Ballet, Molnar performed in Forsythe’s 1989 Enemy in the Figure, which she describes as “a masterwork” and which she is bringing to Vancouver for its Canadian debut in Ballet BC’s November bill.

Enemy in the Figure contains “an enormous amount of responsibility for the dancer,” she says. She is referring to moments of improvisation that take courage and quick thinking to navigate: exactly the kind of challenge for which she has been grooming her troupe.

At a summer rehearsal for the piece, the dancers listen to notes on what to improve and experiment with. Thomas McManus, who was brought in from Forsythe’s team along with Ayman Harper to help stage the ballet, talks about the need to go to the edge in a particular spin. “If it’s a bit precarious,” he says, “it will keep the momentum up.” The props (a rope, a large stage light) are readied, Thom Willems’s music crashes forth, and the dancers launch into space. As they snap, crackle, and flash through this brilliant, busy work, they do dare the edge. That momentum—the art at the centre of the room—is elating. When it’s over, Molnar is smiling broadly.