Alejandro Escovedo turns to me and points: “I want to see more of this lady’s photographs!”

Bev Davies and I are among a small crowd of insiders and autograph-seekers post-show at The Pearl on Granville. In getting Escovedo to dedicate an inscription “To Bev,” I’ve shown him an article on my blog with two images of him playing here in the 1980s with country-punk band Rank and File.

Escovedo is an unassuming, polite man, but at such moments, his charisma rockets—he’s suddenly the guy who has shared the stage with Bruce Springsteen.

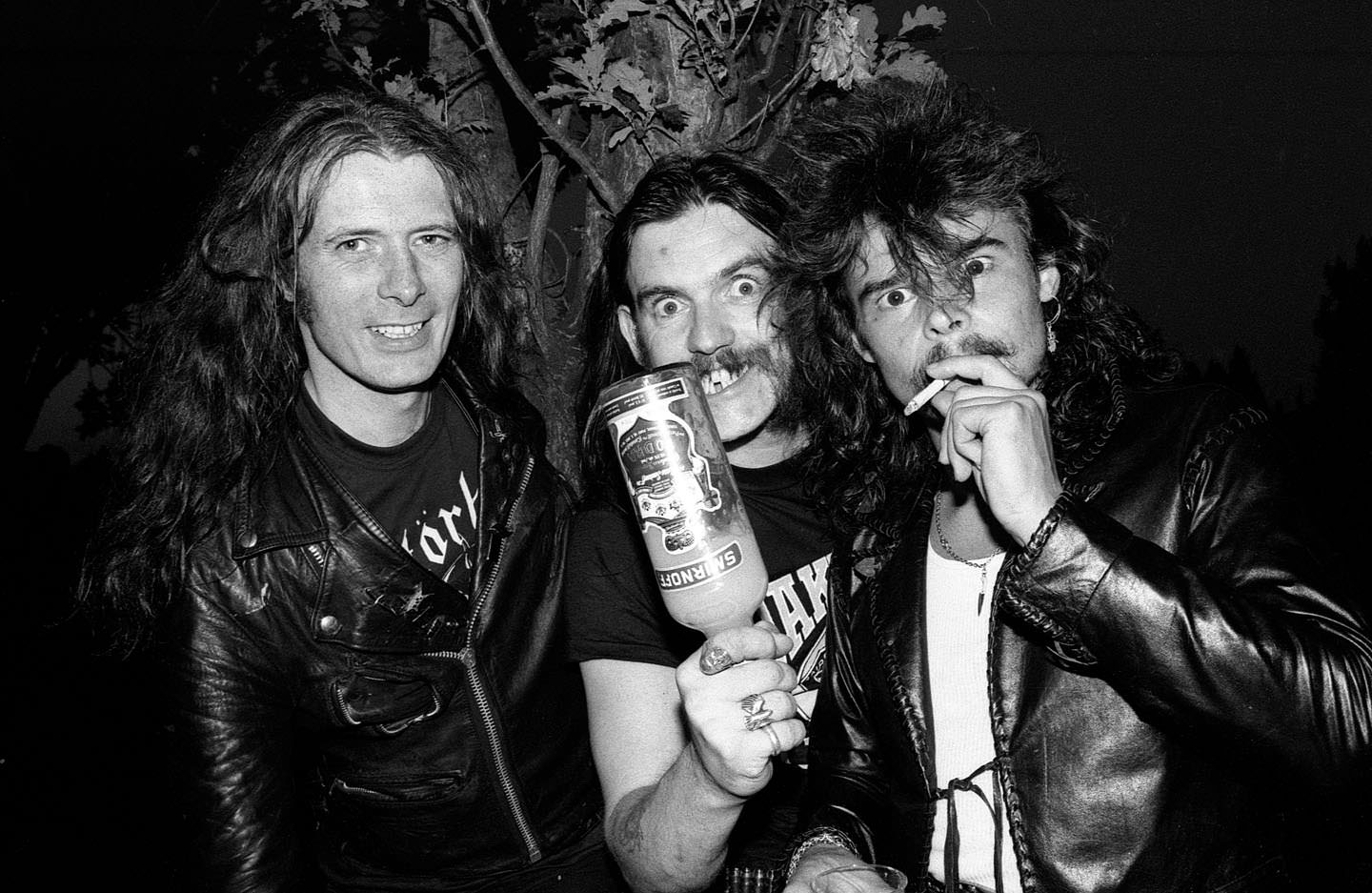

His command is one of my favourite reactions to Bev’s photographs, up there with something said by Lemmy Kilmister, on seeing a photo Bev took of Motörhead outside Kerrisdale Arena in 1981, where they had opened for Ozzy Osbourne. Bev explains that she “had been downtown with them at an in-store earlier in the day, and they’d given me my pass,” but Osbourne’s people wouldn’t let her into the arena to shoot, so Lemmy, Fast Eddie, and Philthy Phil came outside after their set and goofed around on the lawn. Three decades later, backstage at the Vogue, Lemmy saw his snaggle-toothed grin, front-and-centre in Bev’s picture, and declared, “Those are my old teeth!”

Motörhead outside Kerrisdale Arena, July 15, 1981.

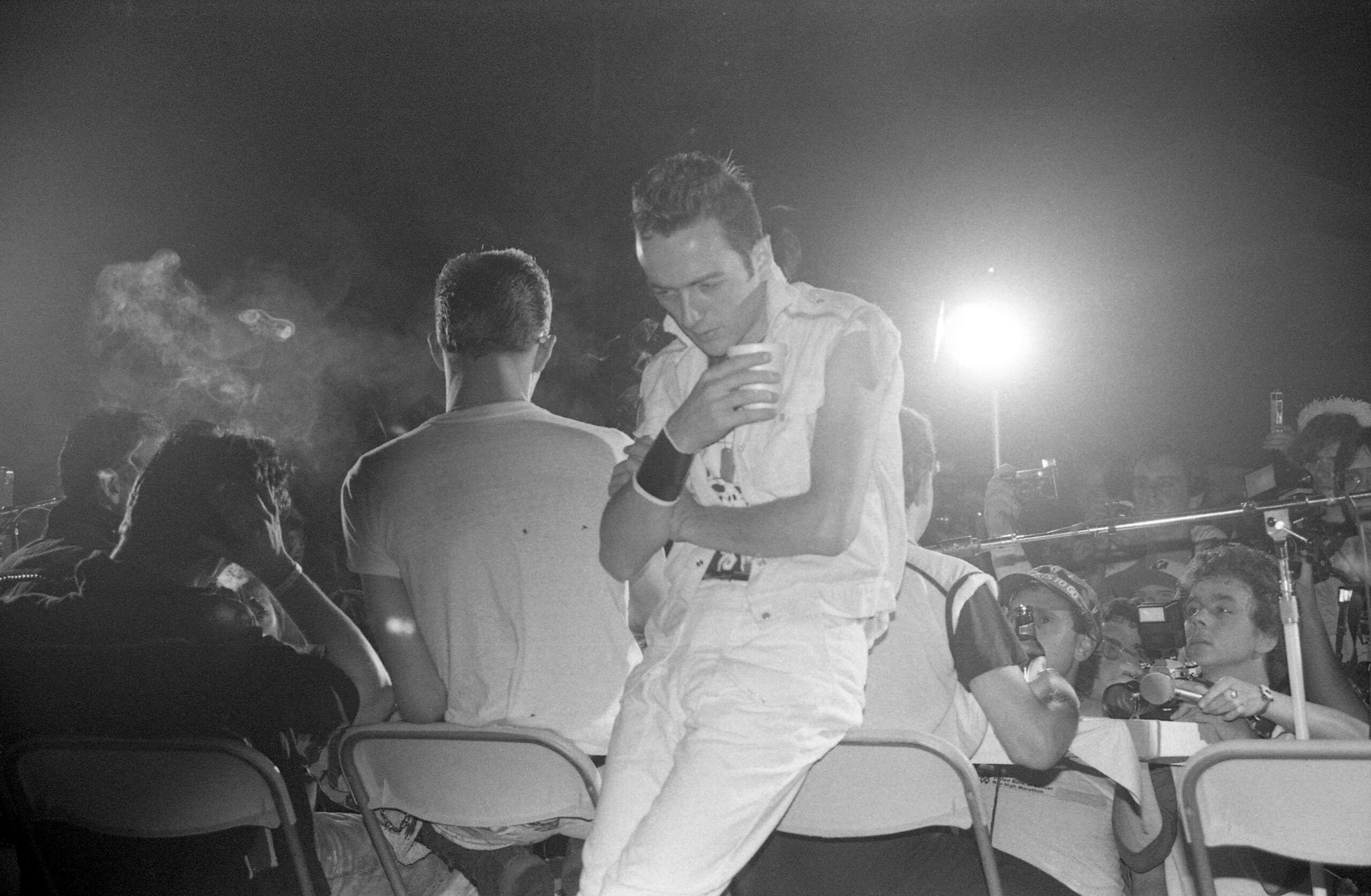

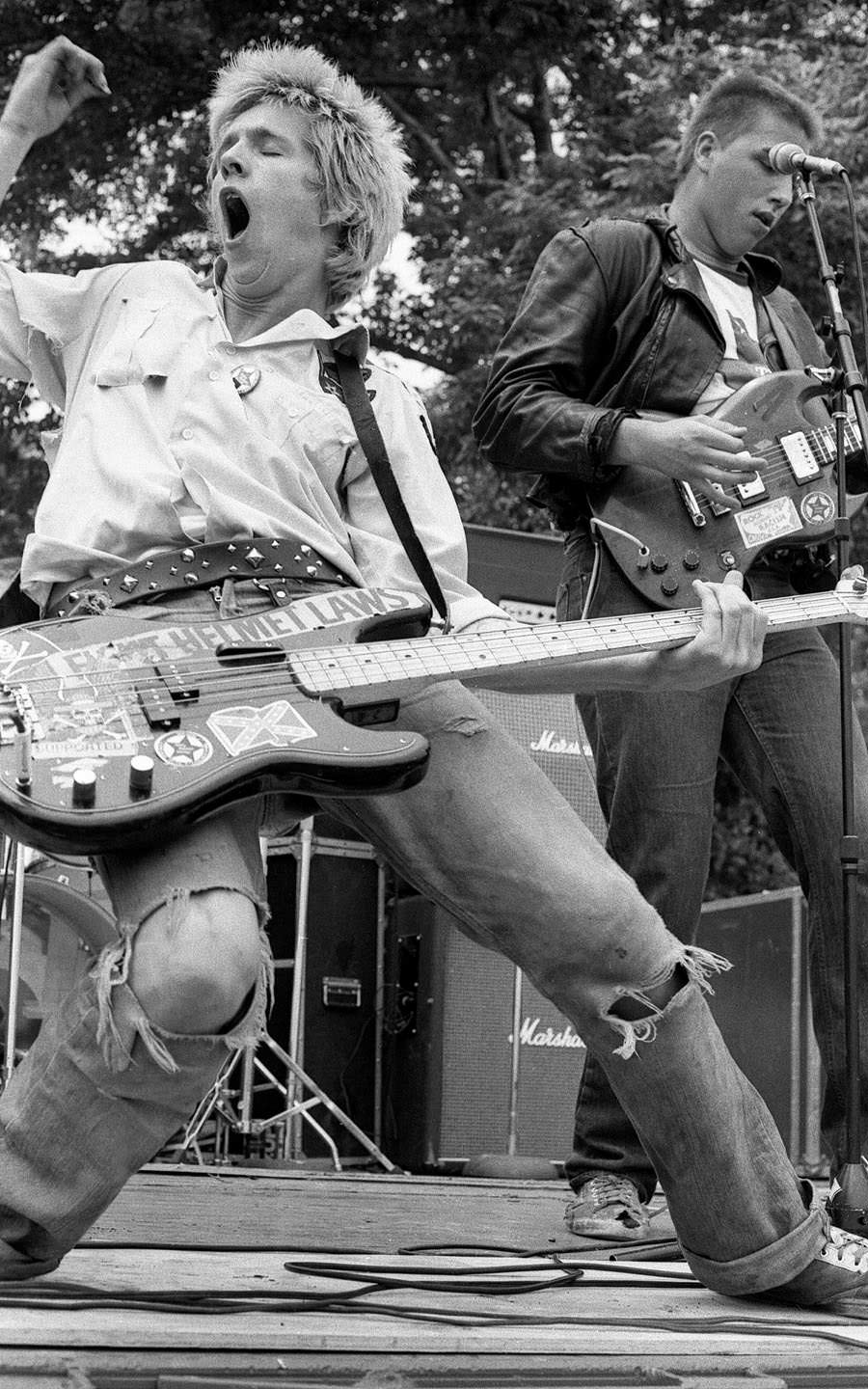

Tony Kinman, Sid Sick at Gore party, May 19, 1979.

Bev has plenty of other stellar photos of out-of-towners, from The Clash at the 1983 US Festival in San Bernardino to a singularly menacing image of California hardcore band Black Flag in front of a house on Victoria Drive. But while she has photographed everyone from Madonna to Pope John Paul II (with The Georgia Straight publisher Dan McLeod’s stern proviso that he didn’t want to hear her telling people, “I shot the Pope!”), the core of her work is local: she’s one of the key documenters of the original Vancouver punk scene, from 1979 to 1984.

I first met Bev in 2007 at Under the Volcano in Cates Park. She had recently returned to photography after a 15-year hiatus. She had stopped taking photos in the late 1980s, when, having left The Straight, she found it increasingly difficult to get cameras into venues. It was a combination of digital convenience and the desire to shoot The Brian Jonestown Massacre that brought her back.

We have collaborated frequently since then. I’ve interviewed her for German and American magazines. And whenever punks come to town who I plan to write about, I still bug her to see if she ever shot them. When we hit pay dirt—as with Escovedo—people tend to get exc›ited.

Davies, a graduate in etching and printmaking from the Vancouver School of Art (later known as Emily Carr), had taken a summer course in photography with Randy Bradley but hadn’t, at that point, found her subject: “I was going around photographing my family and the street and people I didn’t know. And then I went to D.O.A.,” at a Burnaby gig in March of 1979, and went, ‘Hot damn, now I have something to photograph!’”

D.O.A. at the back door of Smilin’ Buddha Cabaret, September 20, 1980.

Roy of Friends Records and Joe Keithley at a D.O.A. party, Smilin’ Buddha, June 1981.”

East Van Halen at Smilin’ Buddha, May 2, 1981.

She didn’t have her camera at that first gig but brought it to D.O.A.’s next show, maybe a week later (she was shooting on Canon, with Ilford 400 ASA film and almost exclusively in black and white). It became her practice to bring prints of her images to the band’s next show and hand them out to the people she’d photographed.

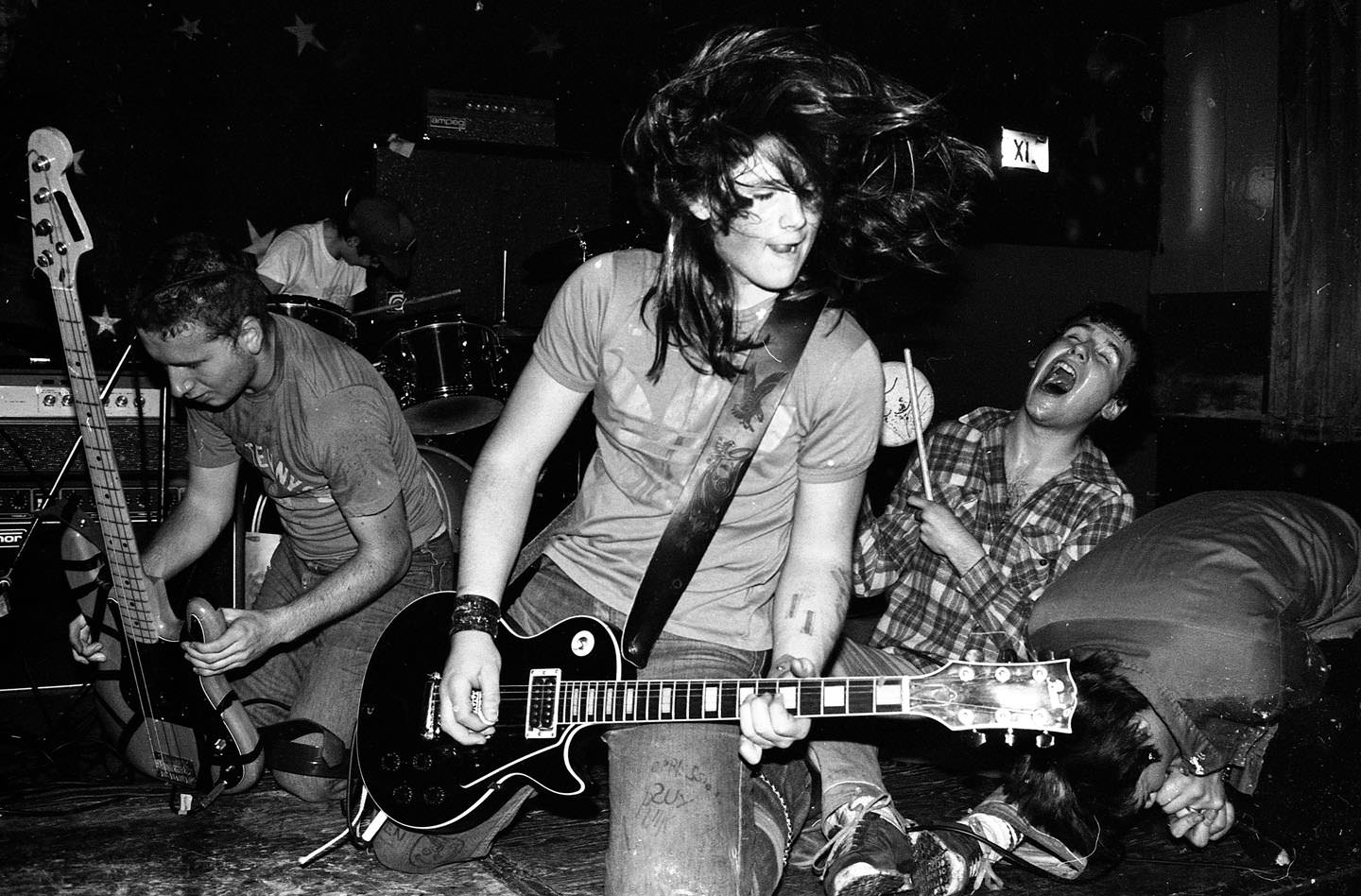

One of her most famous photographs—a nine-foot-tall print of which hangs in The Punk Rock Museum in Las Vegas, and which has appeared in countless publications and even on a limited-edition Skull Skates skateboard—is of Randy Rampage in Chicago, playing with D.O.A., June 9, 1979, as part of a Rock Against Racism gig. It’s on the 32nd roll of film Bev shot once she began documenting the Vancouver scene.

“It was probably three or four months after I’d started photographing,” she remembers. “D.O.A. told me that they were going there and that it was a big show, out at Lincoln Park”—the first major concert there since the 1968 Democratic convention riots. “They said I should go, and I said, ‘Well, if I win at bingo, I’ll go,’ and then as it got closer to the time, I thought, ‘What if I win at bingo the day after they play, and I didn’t go?’ So I thought, ‘Oh, the heck with it. I’ll fly to Chicago.’”

Randy Rampage, Joe Keithley, and D.O.A. at Rock Against Racism, Lincoln Park, Chicago, June 9, 1979

Shooting on film was a very different experience from digital, Bev explains, referring to the image of Rampage. “I didn’t know that I had this picture until I went home and developed the film,” she says. “Probably I had 12 rolls of pictures that I shot at the show,” each with 34 to 38 images on them, which she then had to bring back via plane, “asking them to pass the film around so it didn’t have to go through the X-ray machine.” She would then process the film in her own bathroom-cum-darkroom, seeing what emerged—a sort of excitement that is gone from the age of digital, she says.

“Never show the band the contact sheets. They’ll pick the ones you don’t want to print.”

At my request, Bev digs back into the roll to show me the images before and after the iconic one of Rampage to see what they look like. It’s interesting to see, but there’s no question that emotionally, compositionally, performatively, the image in question is the one.

She says she learned quickly to just let the bands do what they want in front of the camera for posed shots, but after that, it’s her prerogative to choose the shot. “Never show the band the contact sheets,” she adds. “They’ll pick the ones you don’t want to print.”

She also doesn’t crop the image. “What’s in the image is all there is, and though I own the whole image, I wouldn’t just go in on Randy’s face and print that separately.”

More than once during our conversation, she has referred to the photos as her friends—not pictures of her friends, but her friends in themselves, more meaningful now because so many people in Bev’s photos—Rampage, Wimpy Roy, Dave Gregg, Brad Kent, and others, including, of course, Lemmy—have passed on. “Your question about this photo of Randy, and the one before it and the one after it, I’m going to look now, but it’s not something that I’ve ever thought of because this picture is in my heart.”

I know what she means. I met Rampage more than once, interviewed him, and saw him live, but if you say his name, the first image that comes to mind is Bev’s photo in Chicago.

And if these images are indelible for me, they’re doubly so for the person who took them. “These are pictures that I’ve lived with for the last 40 years,” Bev says. “They’re as real to me as anything else is.”

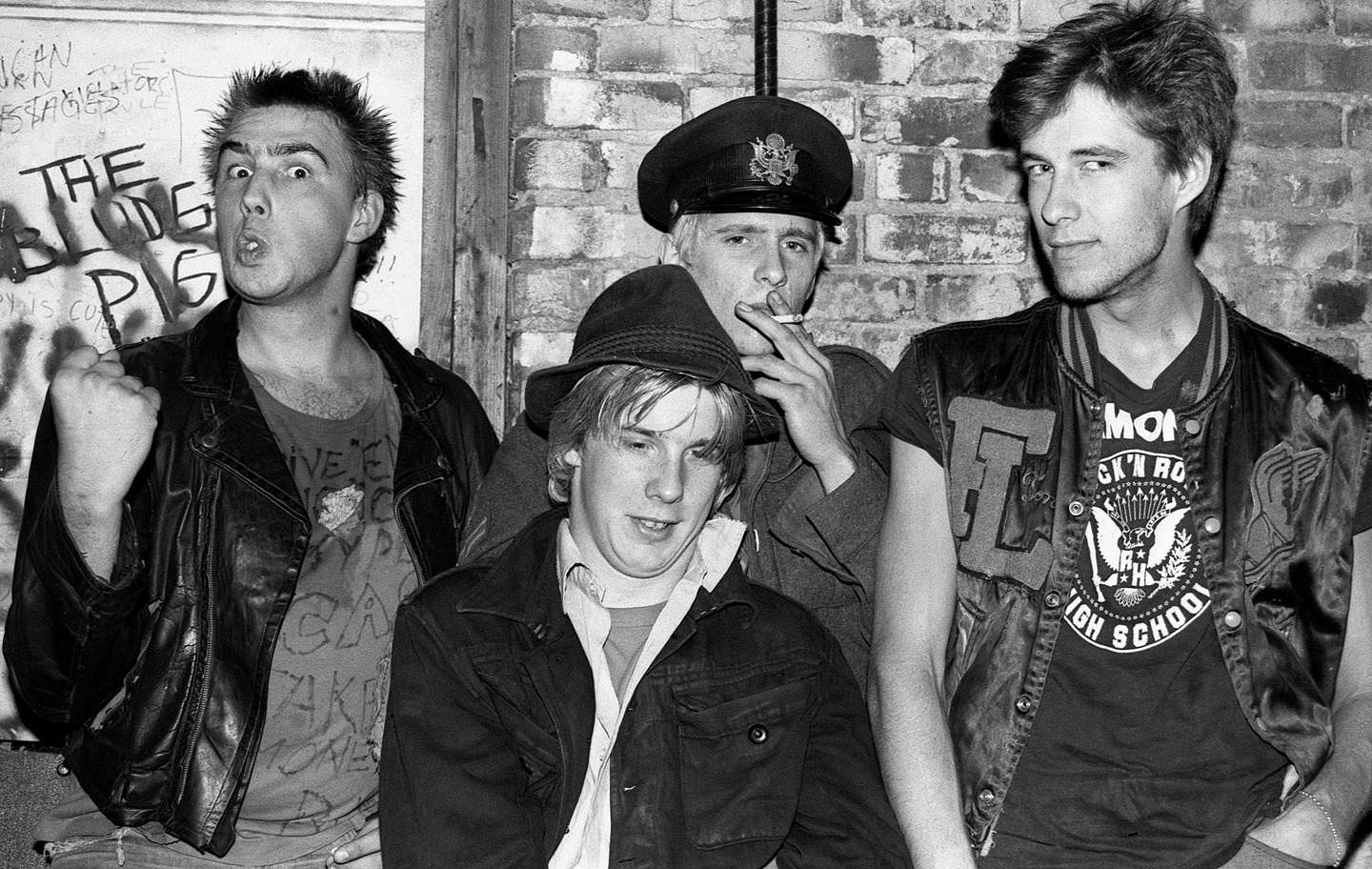

Jim Bescott, Barry Taylor and Art Bergmann, the Young Canadians, February 1980.

Sid Sick and Wimpy Roy, Rude Norton, at Smilin’ Buddha, June 21, 1979.

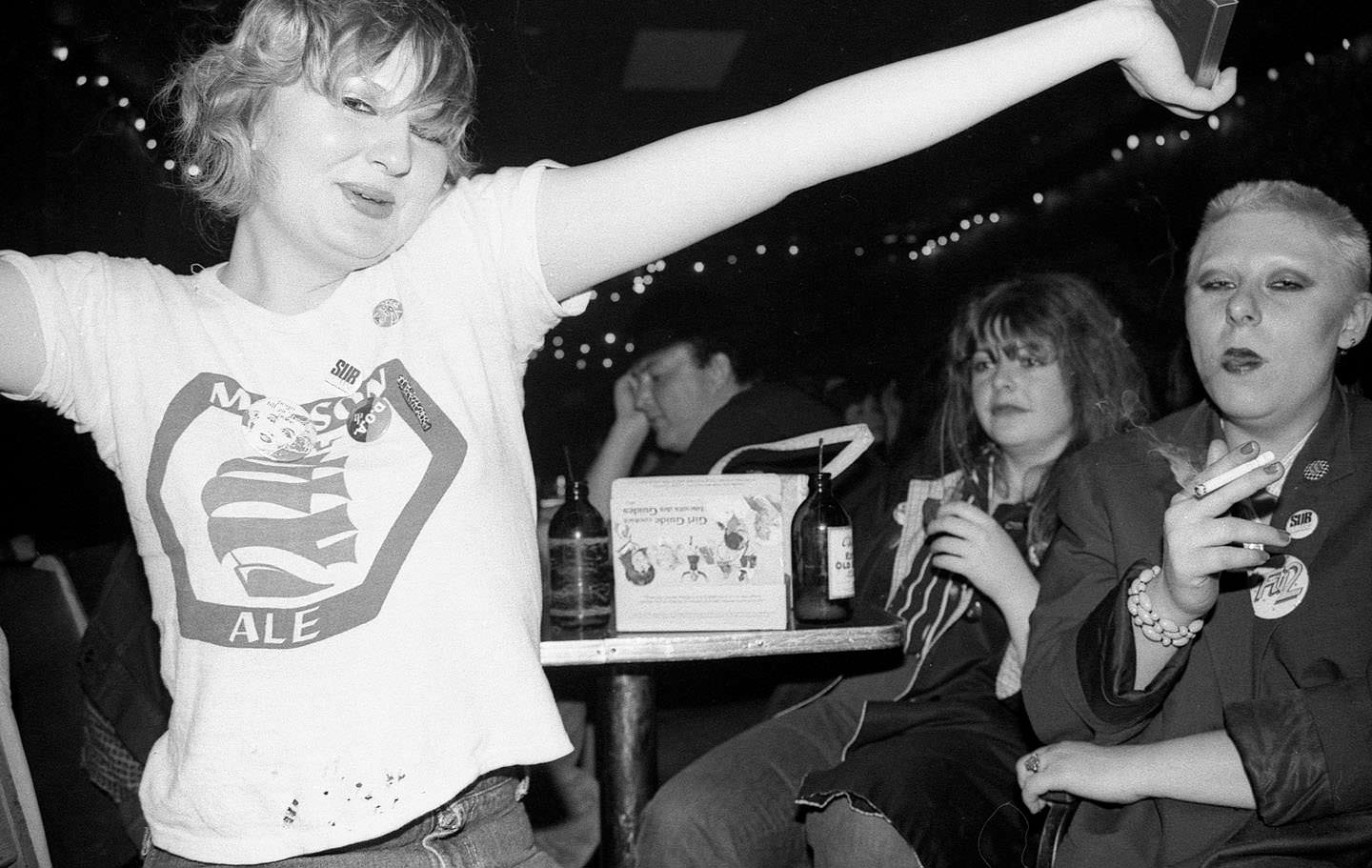

Flo, Miss Mustard, and Sally at Smilin’ Buddha, April 1980.

Read more from our Autumn 2024 issue.