When 33-year-old marketing executive Alex Lowe needs to charge her Tesla, she piles her golden retriever Simon into the car and drives over to North Vancouver’s Ray Perrault Park. She pulls up, hooks up the car to the charging station, and then takes Simon for a walk before the two-minute stroll home. It’s a busy park, often full of kids on swings in the playground, soccer players dribbling balls, and tennis players volleying back and forth, but there’s usually an available charging station, where she can park her electric vehicle overnight for a full charge at no cost.

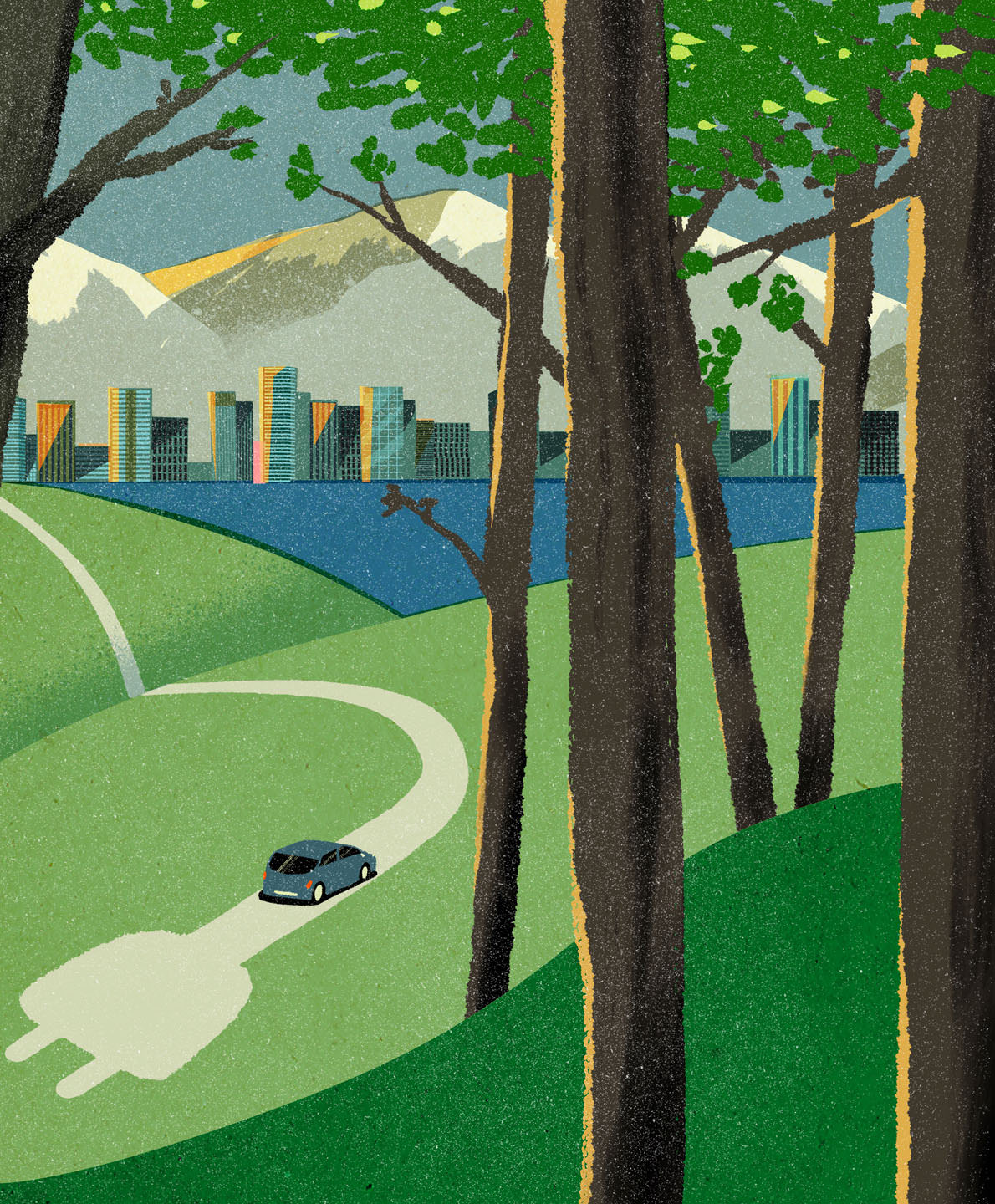

It’s a lifestyle more and more Metro Vancouverites are embracing, with electric vehicles reaching nearly 23 per cent of all new cars sold in B.C. last year—the highest rate in Canada, where only 11 per cent of new vehicle registrations across the country are zero-emission. B.C. even rivals California, the North American hub of tech wealth and early adoption, and surpasses every other American state. Of the more than 100,000 EVs insured in B.C., nearly 80 per cent are in the Lower Mainland, ICBC statistics show. Vancouver, with its reputation as a land of environmentalists and nature-lovers, is on the road to be one of the great EV capitals of North America.

British Columbia, of course, has history when it comes to green issues: Greenpeace was founded in Vancouver in 1971; environmental protests to save old-growth forests and stop oil and gas pipelines continue. Local momentum on electric vehicles has been growing for more than 15 years, with the carbon tax implemented in 2008, the same year as the release of the first Tesla, and Vancouver’s Greenest City Action Plan adopted in 2011. In 2019, the City of Vancouver declared a climate emergency with a plan to accelerate the shift to EVs and expand the number of charging stations, and now requires all residential parking spots in new development applications, except visitor stalls, to be EV-ready. Recently, Tesla chose Vancouver as home to what will be its largest service centre in North America, a 120,000-square-foot facility to open in 2026.

Werner Antweiler, associate professor at the UBC Sauder School of Business, attributes B.C. residents’ embracing of environmental concerns and climate change mitigation efforts to the “green halo effect”—the reputational boost people and companies receive from appearing eco-friendly.

Blair Qualey, president and CEO of the New Car Dealers Association of BC, agrees that British Columbians’ environmental sympathies have meant more EV early adopters. “We’re living in such a beautiful province, and I think everybody wants to try and maintain our natural environment as best we can,” he proffers. “With the wildfire situation across the province, I think that’s really woken many, many people up to the impacts of climate change in our backyard.”

But beyond their urge to save the planet, Qualey sees other crucial factors driving people to buy EVs, calling it a “three-legged stool,” including rebates, convenient charging infrastructure, and education. New car dealers work hard to have EVs available to test drive at the Vancouver International Auto Show, because once people have driven an EV, they’re more interested in buying one, he says.

Teslas are the most popular EVs in B.C., with close to 55,000 vehicles registered, but other models are also leaving the lots, with more than 1,800 Ford F150 electric trucks and nearly 3,000 electric BMWs on the roads.

B.C. also has a zero-emission vehicle mandate requiring all light-duty vehicles sold be electric by 2035, with escalating targets, rebates, vehicle sales mandates, and public charging stations all bolstering the argument for making the switch.

Lowe bought her white Tesla Model 3 in 2019 after weighing the economics of paying more for a vehicle upfront against the weekly cost of gas. Her lifestyle includes a lot of driving—besides commuting to work, she plays fast-pitch softball in Richmond and volleyball in Port Moody.

Antweiler, who drives a plug-in hybrid EV, says the benefits are worth the extra upfront cost. “There are fewer maintenance costs every year—no oil changes and no engine parts that go kablooey because of wear and tear.”

The range of EVs is getting longer as batteries get cheaper and bigger, he says, and charging is becoming more convenient. “You can come home at the end of the day, and you plug in your car in your own charger,” he notes. “This is the gold standard.”

He lives in a strata building where owners can pay for and install chargers in their own parking spots, connected to their own electricity meter. The energy grid, he argues, despite being tested by climate change and drought conditions, can handle the added demand from EVs as long as most people recharge overnight. “B.C. has the ideal sweet spot electricity grid, where our big reservoirs are like big batteries, so we can do storage.”

Lowe only needs to charge her Tesla a couple of times a week, and if she can’t make the overnight charge at the park work, there’s a Tesla Supercharger at the London Drugs nearby. Or she can take Simon for a walk in Capilano River Regional Park, where there’s an off-leash area for dogs, centuries-old Douglas fir trees and western red cedars, and a tiered salmon hatchery on the Capilano River. In the parking lot, there are two EV chargers, so while Lowe walks her dog and enjoys her nature fix, her car is filling up.

Read more from our Autumn 2024 issue.