I was thrown head-first into Jack Shadbolt’s artwork as a young summer intern with the Vancouver Sun in the mid-1970s. The show was titled African Dream Series. The paper’s venerable art critic was sidelined by a health crisis, and I was on deck. I recollect a motley collection of vaguely organic forms (animal? mineral? vegetable?) floating on murky backgrounds with abstract hints of landscape. I was seriously flummoxed.

Even fresh from Ontario, I knew that Jack was a Big Deal on the West Coast—but not why. Without context (or access to Google), I struggled to find polite artspeak for “dog’s breakfast.” What, if anything, were these paintings saying about Africa? Or dreams? I ducked and weaved. It was not my finest hour, but nor was it, apparently, Jack’s.

Those pieces have largely sunk from sight in the public record, elbowed aside by his more powerful works: the vaunted triptychs of mutating butterflies, the emotionally charged landscapes, the surrealist-tinged symbols of the 20th century’s angst. Was this just Jack cynically getting himself out of a momentary jam? Here’s the story I’ve recently pieced together.

Needing to deliver a show to his representing gallery, Bau-Xi, he found himself short of both new product and time, after months out of the studio travelling internationally with his wife, Doris, during her curatorial sabbatical from the Vancouver Art Gallery. But Jack prided himself on his practicality, and he was frugal as well as unevenly prolific. So he rescued from storage a stack of, shall we say, “less-well-realized canvases” from 1961-62, had another go at them and, voila, the African Dream Series. (Should you come across one, it may be double-dated: J.Shadbolt ’61/’75.)

Grey Morning, 1981. Painting reproductions courtesy of SFU Galleries. © Simon Fraser University.

Despite the rocky start, as time passed and our social circles overlapped, Jack and I would happily deep-dive into discussions about the psychology of colour perception or some such aesthetic eye-glazer, each of us grateful for a respite from cocktail small talk. The physicality of the art experience excited us both, the upsweeping mental, emotional, skin-tingling quality of those encounters whether as maker or viewer. I thought I knew Jack fairly well, as we tend to think we know an artist when they’ve shared their way of seeing the world with us.

Then, four years ago, in serendipitous circumstances that I write about at the end of Jack Shadbolt: In His Words (to be released this fall), I sat down to read his archived youthful letters, his revealing personal journals and soul-bearing poems. I looked at his artwork again, and I realized I really didn’t know jack—or Jack. An encounter with him had, again, flummoxed me. It asked me to consider how well we know anyone: Our closest friends? Our intimate partners? Ourselves?

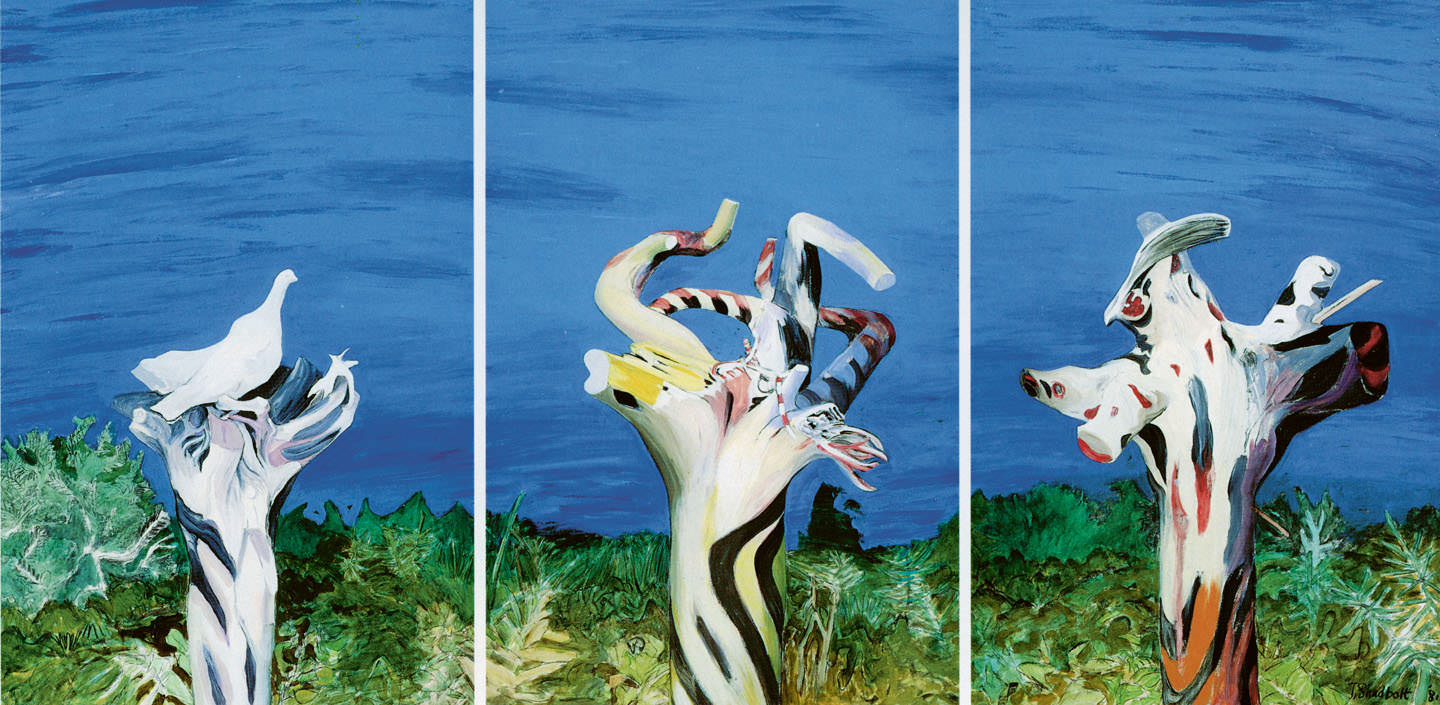

Equivalent for Landscape #1, 1980. Painting reproductions courtesy of SFU Galleries. © Simon Fraser University.

I discovered a private person riven by deeply conflicting tendencies and shaken by nightmares, who sought wholeness and release by transforming all of his life experience—body and soul—into expressive forms, colours, textures. He was always a work in progress, literally dying surrounded by canvases in his studio just short of his 90th birthday. “Who says an artist should be ‘finished’ with anything—or that it really matters when a particular work was done?” Jack wrote in his final exhibition statement, concluding “Hindsight is a great teacher.”

I’m guessing he wrote that with a wry smile. Although I didn’t know it in 1975, he had a habit of periodically resurrecting past work, reassessing, pushing his insights further. Sometimes he got an African Dream, sometimes he produced transcendence.

I decided to try a similar experiment, not to write a standard biography but to reach into the treasure trove of pieces of himself that Jack had left behind and see if they could be newly fashioned. I aimed for something as richly textured as the dressmaking fabrics that had entranced him since childhood and the butterfly wings that some see as his most beautiful and poignant work.

Perhaps we all come to understand ourselves bit by bit. In the process of making In His Words, pieces of myself came together. Something comparable might happen to you if you read it. In fragmenting times, it’s deeply therapeutic when the pieces come together and make joyous sense of our difficult, conflicted human lives. It might explain why the literary memoir is the growth genre of the moment. I like to think Jack would agree even if he never quite got round to writing his own.

Read more from our Autumn 2024 issue.