Rob Feenie takes a beat. Rocking gently back and forth on his heels, he waits at the edge of the room, his eyes darting from table to table and plate to plate. Apparently satisfied, he smiles broadly and plunges into the fray, pausing at each table to chat, occasionally going so far as to pull up a chair. By the time he stops next to our table, his eyes are twinkling with joy.

“I love this,” he says, his face lit up with excitement.

It’s been a blisteringly hot July day, but inside Le Crocodile by Rob Feenie, the air is wonderfully cool, the restaurant—which has been open two weeks—brightened and modernized as part of its reinvention. After four decades of serving up his signature French classics to happy diners, chef and owner Michel Jacob retired in April, selling his beloved Le Crocodile to Feenie. The two men go way back—Feenie worked for Jacob in the original Le Crocodile on Thurlow Street and moved with him in 1993 to open the Burrard Street location. The news that the French veteran’s former mentee would take over the stoves felt both exciting and entirely natural. Early bookings have been brisk and show no signs of abating.

Nor should they: our meal is excellent. Delicate, chilled watermelon soup is poured over tiny cubes of cucumber, perfectly poached side stripe shrimp, and fronds of dill. Japanese-influenced kobujime hamachi (cured amberjack) sits in a pool of light but startlingly punchy sauce punctuated by yuzu, soy, and stone fruit. And the richness of sablefish glazed with soy and sake is cut by another spectacularly intense and well-balanced acid-forward broth.

It’s been a minute—17 years, in fact—since the Burnaby boy turned internationally acclaimed chef danced in the fine dining arena. In 2007, after a public spat with the new owners, he walked away from Lumière, the restaurant he founded in 1995 and once owned (along with its more casual sibling, Feenie’s). It was, by any measure, a catastrophic end to a fast and furious career trajectory that had seen Lumière earn an AAA Five Diamond Award and an exacting Relais Gourmands designation, with Feenie becoming Canada’s first successful Iron Chef America challenger and garnering the respect and friendship of the world’s top chefs along the way. To add insult to injury, he was locked into a brutal non-compete clause, leaving him few options to maintain his standing in the culinary scene.

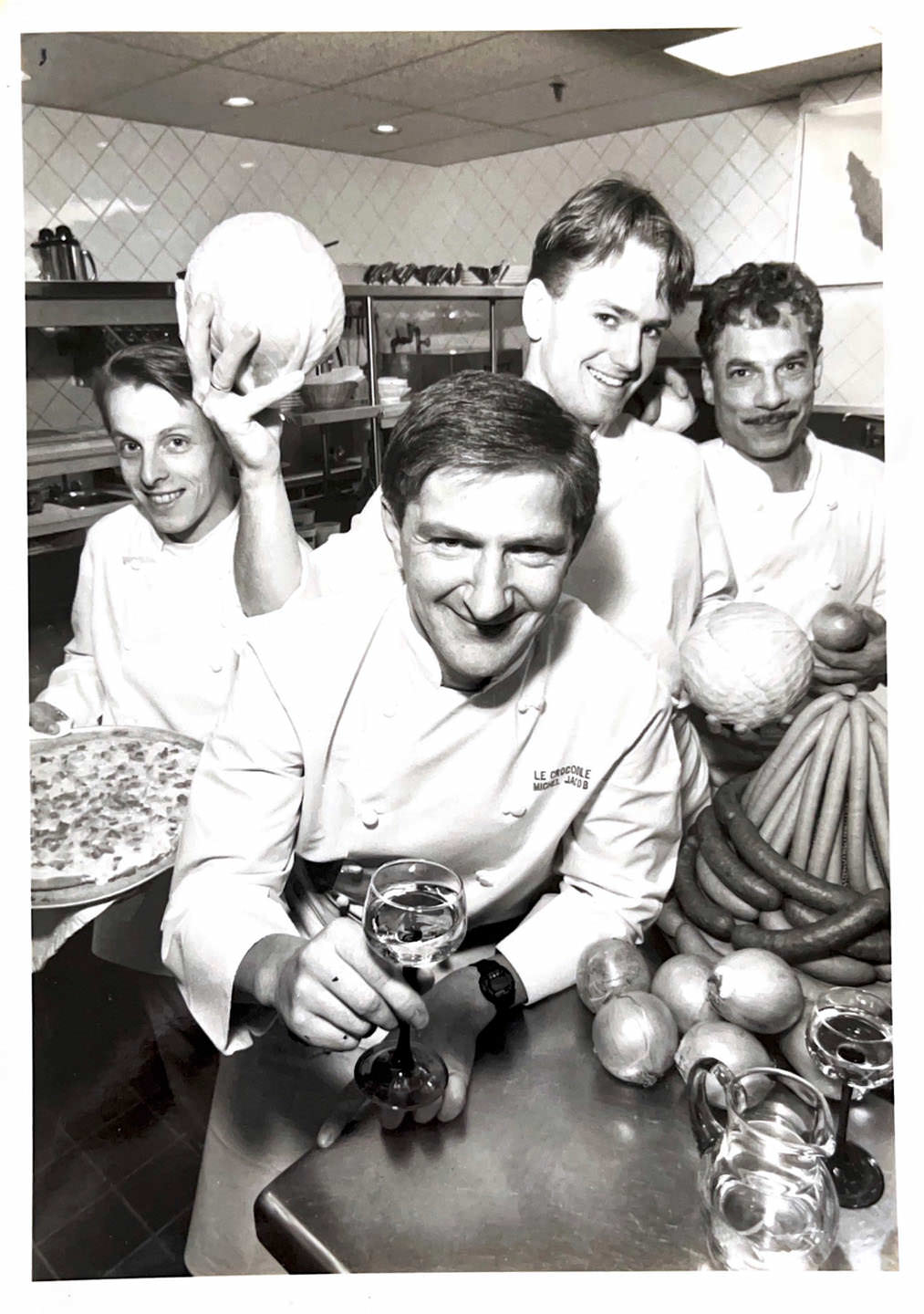

Michel Jacob and Rob Feenie at Le Crocodile in the early 1990s. Photo courtesy of Le Crocodile.

I first tasted Rob Feenie’s food after moving to Vancouver from London 20 years ago. The tasting bar at Lumière in that unassuming stretch of Kitsilano on West Broadway quickly became my Friday night go-to. Smart enough to dress up for, but with a dazzling deal of menu items all priced at $12, there was never a good enough reason to go elsewhere. Roasted bone marrow mopped up with buttery brioche, the legendary kuri squash and mascarpone ravioli that then Globe and Mail restaurant critic Alexandra Gill described as “sex on a plate” (she was spot on, by the way), and my first encounter with the glory that is west coast sablefish—everything was as good as it could possibly be. It was the place du jour for those of us unable to stretch our credit cards to afford the restaurant proper, and it had the aura of a New York hotel bar of yesteryear.

Then, in what felt like a flash, Feenie was gone, moving to Winnipeg and taking up an offer to revamp and elevate the menu at casual chain Cactus Club. And what was supposed to be a soft landing for a few years while he ran down his non-compete obligations turned into a 15-year fine-dining hiatus.

“I got this huge parachute from Cactus Club because Jim Stewart, one of the partners at the time, his mum and dad are my mum and dad’s best friends,” Feenie tells me when I return to the restaurant in August to talk to him.

“I never really thought about it,” he says of Stewart’s offer. “I just said, ‘Why not? Let’s give it a try.’ I went there for two years, and then the two years turned into three more, and then the three more turned into…” he trails off.

The intention, he says, was always to return to fine dining. Lumière, then overseen by Daniel Boulud, finally closed in 2011. “I was going to buy it,” he reveals. As my eyebrows shoot up, I see the vaguest hint of a smile before he adds, “It wasn’t worth much then.”

He says he chooses to not dwell on what happened, that he no longer cares. The latter may or may not be true, but his decision to sidestep discussing it suggests that his almost two decades out of the spotlight have brought him a degree of equanimity—or at least the maturity to know when to keep his thoughts to himself. In any case, right now, he has more pressing things on his mind. Specifically, his new menu.

Le Crocodile regulars were a fiercely loyal bunch. Jacob fed generations of entire families, Feenie’s included. This is where birthdays, graduations, engagements, and other milestones were celebrated over plates of escargot and veal medallions with morels, or bowls of the signature tomato and gin soup followed by Dover sole deboned tableside with heaping plates of shoestring fries to share. The menu was delicious, rich with butter and cream, and comfortingly predictable. Change was something that happened in other restaurants, not here.

It’s only been a month since he opened, and Feenie is working hard to respect Jacob’s legacy while also creating his own vision for the restaurant. In some ways, it’s not so different: he trained under Jacob and also travelled and staged in Alsace under Émile Jung, Jacob’s own mentor. He mentions several times during our conversation that his style is simple, uncomplicated food. And comparing his menu with Jacob’s, there appear to be only a few changes. Yes, there are new dishes, notably those incorporating Japanese ingredients, but the snails, frogs’ legs, veal, tomato gin soup, Dover sole, and more remain. (The fries, it should be noted, are no longer shoestring.)

“I wanted to be like a Daniel Boulud, a Thomas Keller, a Joël Robuchon. And I felt that I took Lumière as far as I could to get to that point.”

From a stuffed backpack, he pulls out a thick sheaf of old Lumière menus as well as one of Jacob’s from Le Crocodile. He starts running through the latter, dish by dish, pointing out what he’s kept and what has changed. Mostly, the dishes that remain have been tweaked—the mayo has gone from the beef tartare, the mimosa salad has a new name and the traditional diced egg white has gone, the veal is a different cut, the Dover sole is a larger fish…

It may not sound like the ground has shifted that far, but underneath the tweaks to these classic dishes sits something that—in the context of a French restaurant—is seismic. Across the entire menu, he has transformed the sauces, removing all starches and flour in favour of lighter, more intensely flavoured reductions. Add that to his love of Asian ingredients, and the revolution—albeit a quiet one—has begun. And customers have noticed.

“I think that there are some Michel regulars who have come who might not come back,” he says. “But I think for every one of them, three new people will come who were the old Lumière people.”

Herb-crusted saddle of lamb. Photo by Jamie-Lee Fuoco.

The young Rob Feenie fell in love with food while living in Europe for two years. He was just 16, pursuing his first passion: hockey. Off the ice, he was getting a primer in eating well. Back home in Burnaby, his Irish tea-drinking family was bemused at their teenager making himself an espresso every morning, going shopping for ingredients, learning from their Japanese neighbours, and preparing multicourse dinners.

“Then,” he recalls, “all of a sudden, I said I wanted to be like a Daniel Boulud, a Thomas Keller, a Joël Robuchon. That’s what I wanted to be. And I felt that I took Lumière as far as I could to get to that point.”

Lumière closed long before Michelin arrived in Vancouver. Rumours that Feenie was coming back—he did short stints at both the Vancouver Golf Club and Bacchus at the Wedgewood Hotel in the past two years—raised speculation that he was being lured by the possibility of an accolade.

He shakes his head. “When I was 29, 30, and was opening this place, all I wanted was accolades,” he says, after taking a moment to consider. “Typical young chef with a big head. The more I got, the bigger my head got.

“I’m a perfectionist, and perfection is impossible,” he proffers. “None of us are perfect, but if I at least strive for perfection, I’ll get excellence. If I strive for excellence, maybe I would get average. Simplicity is much more difficult to achieve than complication.”

The list of chefs who collaborated on dinners at Lumière—Gordon Ramsay, Michel Roux Sr., Alain Passard, Santiago Santamaria, Thomas Keller, Charlie Trotter—is staggering. “I was like a kid in a candy shop,” Feenie admits. “A lot of these things happened to me in my mid-30s, and that’s why maybe my head got a bit big, but I realized I can do this,” he says.

“Lumière in its heyday would have had a Michelin star, at least one, maybe two,” Colleen McClean, former chef de partie at Lumière and later chef de cuisine at Feenie’s, asserts. Now running her own artisanal bakery in Powell River, McClean considers her time working with Feenie critical to her culinary career. “It changed the trajectory of my life,” she says. “Rob was a generational talent in Canada, and I learned an incredible amount from him.

“I also learned how to not run a business,” she adds.

Feenie is open about his failings on that score and grateful for how much he learned about running successful restaurants at Cactus Club. This time, he says, he not only has partnered with investors he can trust, “they will make sure this restaurant is profitable.

“One of the things I’ve learned to do,” he says, “is listen before I respond, pay attention to what people are saying, and not just say it’s my way or the highway.”

His friend Thomas Keller told him to start slow, build the right team, don’t run headlong into it all, he notes, and he has taken that to heart. But this fall, he assures me, the restaurant will look more and more like Lumière. The dishes will be refined, there will be a tasting menu (to begin with, for just one semiprivate table), and there will be ravioli.

He returns to his stack of old menus, excited about replacing the traditional pork choucroute with pickerel, questioning whether he has to keep Jacob’s mushroom soup. Surely, I suggest, now it’s his restaurant, he can do whatever he wants?

“My CDC Mark says that to me all the time,” he responds. “‘Chef,’ he says, ‘it’s your place.’”

Read more from our Autumn 2024 issue. Grooming: Melanie Neufeld for Lizbell Agency. Photographer’s Assistant: Kitt Woodland.