Kenneth Hsieh is an anomaly in music and is rapidly making his way to the top. That’s because he turned things around for himself after what could have been a devastating accident. Now 28, Hsieh was a student at the University of British Columbia when he smashed two of his fingers against a wall while playing handball. He was majoring in piano and percussion at the time. The accident could very likely have spelled the end, at least to a career at the piano. Yet, he still plays, and very well, having found a way around it. But that is just the beginning of the story.

While recuperating, he rethought his career plan. Maybe he could use his hands to conduct. This would mean quite a shift of direction, from executant to executive. But he’d always vaguely entertained the idea of being a conductor. He went to Tokyo to study at the famous Toho Gakuen School of Music, which had turned out such illustrious figures as Kazuyoshi Akiyama (conductor laureate of the Vancouver Symphony Orchestra) and Seiji Ozawa. “It’s lucky they didn’t see my marks from UBC—I was a sloppy student—or I’d never have got in,” he says. The Toho is a school noted for, among other things, its method of training in the precision of hand gestures, which are minimal and precise. Study was intensive, and expensive. Hsieh notes he isn’t rich, and had to find a way of living on about $2,000 for three months. He usually ate only one meal a day while in Tokyo, and he put himself through school on a scholarship and by modelling—he is tall, muscular and strikingly good-looking.

His conducting teacher was an international legend, the great Morihiro Okabe, who was 82 when Hsieh approached him at a train station. Discouragingly, the mentor said he’d had two heart attacks and didn’t want any new students. But Hsieh wasn’t easily put off, and his natural charm proved too hard to resist. Their second meeting was to have been 15 minutes, but stretched to three hours. One thing Okabe said was that if Hsieh had any girlfriends, get rid of them or he’d kick him out. Hsieh said he was right. “I had a girlfriend at the time and noticed that things were going downhill in my work.” One day he got kicked out of a class for wearing shorts. Then, as if out of solidarity, Okabe showed up wearing shorts. He and the gentle but crusty Okabe got very close during their time together. It was a profound shock for Hsieh when, in 2008, Okabe suddenly died while riding his bicycle home after doing some grocery shopping. Hsieh says, “He suddenly got tired and sat down to rest, and he died.” He was buried wearing the tie Hsieh had given him.

Hsieh started out leading an amateur ensemble, the Vancouver Metropolitan Orchestra, which was then housed in a community centre in the Marpole community of Vancouver. They now work out of the pleasant new Michael J. Fox Theatre in Burnaby, but this is still an extreme contrast to the three orchestras Hsieh leads in the new triple-space arts complex in the prefecture of Hyogo, with its sold-out subscription series of 76,000 people. He’s still with his amateur orchestra, returning often to Vancouver to conduct it, which is unusual for a conductor who is on his way up. He’s worked around the world with such great names in music as Krzysztof Penderecki, Bernard Haitink, Simon Rattle, Edo de Waart, Charles Dutoit. And, he is intimately acquainted with the pianists Lang Lang and Yundi Li.

He sees great importance in making a training ground of the Metropolitan Orchestra, keeping it chamber-sized, playing neglected repertoire and steering it towards excellence. It has grown dramatically in accomplishments in his hands. He is strict about what he wants, but is never unpleasant to deal with, knowing the counter-productivity of bad morale. He hasn’t got where he is for not trying. When he was chosen for a two-year term as the assistant conductor of the VSO—which was renewed for a subsequent year—it was by default after the first choice decided not to accept the position. But Hsieh worked out brilliantly and remains one of the best assistant conductors the orchestra has had. The musicians, who aren’t always the easiest to get along with, respect him and, more importantly, like him for his affability, approachability and down-to-earthness. Pianist Linda Lee Thomas describes him as “a treasure”. He supervised the Tea & Trumpets and the Lovers’ Ball series, and such things as cranking out a grueling schedule of Christmas shows all over the Lower Mainland, while attempting to create at least the illusion of seasonal festivity and an atmosphere of spontaneity.

His three years of grunt work proved to be a great training period, which he took very seriously. He always had his nose in a score, and he still does. Aside from occasionally doing the Grouse Grind, he rarely seems to take a break and is usually up to the wee hours. The last time he returned to Vancouver, he was studying the second symphony by Vasily Kalinnikov, which he was due to play in Japan. This is an attractive, Tchaikovsky-like work by a virtual unknown. He gave me a copy and pointed out an interesting detail, a movement that keeps repeating a major third that sounds exactly like the wail of a British ambulance. People loved the performance in Japan, he says.

In July 2007, Hsieh conducted his final official concert for the VSO. It was the 19th annual outdoor free summer concert in Burnaby’s Deer Lake Park. This idyllic event is always a highlight, and the park was packed with people sitting on blankets and listening to music that was written as if meant to be heard outdoors. It included two plangently beautiful pieces by Rachmaninov, both heavy with chromatic harmony, the first of Grieg’s two Peer Gynt suites, and Borodin’s In the Steppes of Central Asia which is poignant with a sense of limitless space over a pedal drone. The orchestra played like a dream, though it was muggy and hot. Hsieh changed from a dark jacket to a white one halfway through. By the end of the concert, which included an encore, both jackets were wringing wet, and his hair hung lank. He slouched with fatigue when he left the stage. It was the only sign he gave that he was exhausted. It was the slouch of a hero.

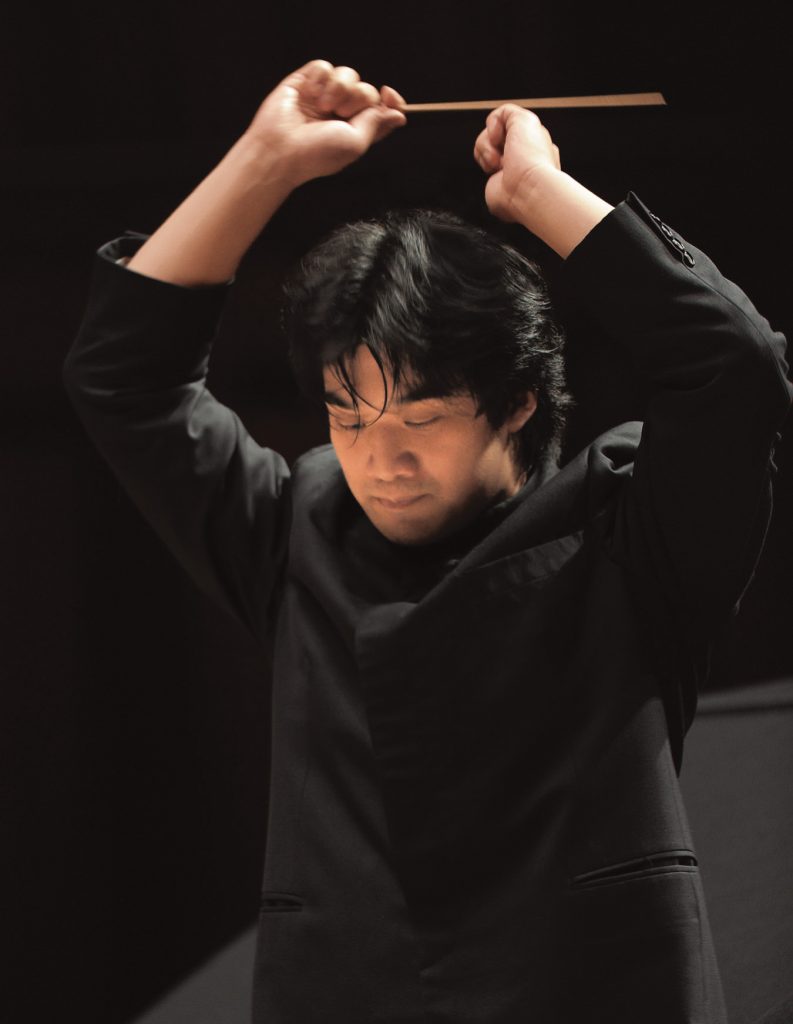

Photos: Myoshi Eisuko ©Crystal Arts Inc.