Changes or developments in the arts are often, mistakenly, described as “evolution”. For example, a familiar story: The Beatles started as a rock ‘n’ roll band covering Chuck Berry and Little Richard with some Lonnie Donegan thrown in for good measure. Lennon and McCartney started writing songs together for the group to play. Then, with the help of George Martin, they began to incorporate a little Karlheinz Stockhausen and Pierre Schaeffer, which revolutionized studio recording and popular music itself, most evidently manifested in the albums Revolver, then Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band and The White Album.

While this development may be interpreted as an increase in complexity, it is not related to the biological imperatives that drive evolution in the Darwinian sense and might better be described as the result of an artistic restlessness. This trajectory—from merely emulating your heroes to synthesizing your influences into a mature, personal style—is a part of most artists’ development. However, some, like the Beatles, take it even further.

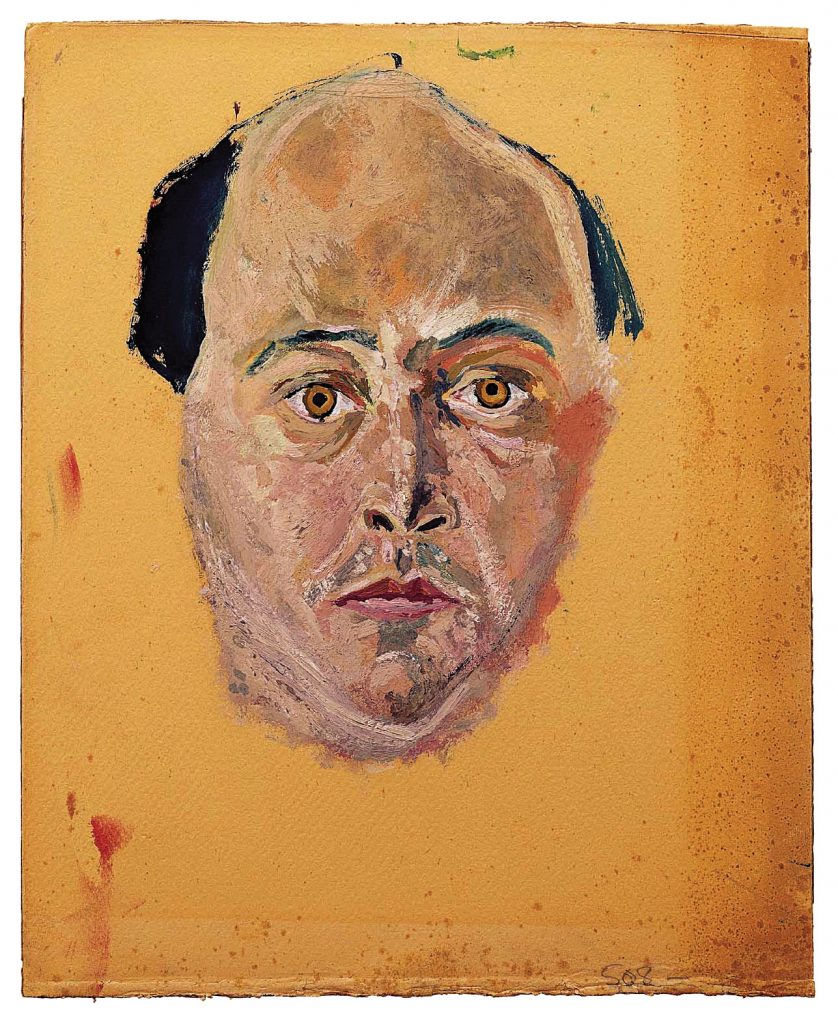

In classical music, the most infamous developmental arc is probably that of composer Arnold Schoenberg. He started writing in the highly chromatic harmonic language of his day (1900, Vienna) and ultimately found himself at a crossroads: either develop a new musical language or continue to reuse the traditional musical syntax. He chose, what novelist Thomas Mann compared to a Faustian pact with the devil, to create a new system of organizing melody and harmony. Many have argued that Schoenberg and his modernist contemporaries and heirs alienated the audience for classical music, permanently, and that this constant striving for the “shock of the new”—to use Robert Hughes’s description of this same impetus in visual art—created a canon of impenetrable music by and for a secret society of initiates.

Charlie Parker and his collaborators caused a similar reaction in their quest for a new paradigm in jazz in the early 1940s. Many musicians and listeners did not understand Parker’s bebop, initially. However, bebop remains much of the stylistic basis for mainstream modern jazz.

This restlessness—the drive to create something new—is sometimes assumed to be the essence of the artistic impulse. However, some artists prefer to work within the established boundaries of their predecessors, making incremental changes to their art form, while others, like the Beatles, Charlie Parker and Arnold Schoenberg break with the past, changing music in a fundamental way. So were the Beatles avant-garde? Some might argue that the avant-garde tendencies of John Lennon were balanced by the more conservative orientation of Paul McCartney. Another complication to this question is the notion that the 1960s heralded a new post-modern age when musicians freely mixed and matched various musical styles. The Beatles certainly seem to represent this aesthetic—compare the last two tracks on Revolver: “Tomorrow Never Knows” and “Got to Get You into My Life”. They are very different tracks, but both are vintage Beatles.

What about music of the last 10 or 20 years? The postmodern aesthetic of creating something new by recycling and remixing the old continues in all genres of music. But, the avant-garde impulse for new and more complicated forms of musical expression is still very much alive. Time will tell, but there are no doubt some artists with avant-garde tendencies in the ever-increasing variety of pop music genres. Public Enemy released several albums in the late 1980s and early 1990s that featured rapper Chuck D and a dense, electronic soundscape supplied by him and Hank Shocklee. Alternative superstars Björk and Radiohead continue to incorporate all sorts of musical influences in their respective idiosyncratic but influential work. In the aggressively non-mainstream world, check out the album Catch Thirtythree and EP I by Swedish math-metal virtuosos Meshuggah.

Music and the other arts do not evolve or even progress in a neat, linear fashion, and considering someone avant-garde or conservative is not a judgement of aesthetic beauty or value. So change is not necessarily evolution. Although, it could be argued that the human urge to create new, personal modes of expression is related to the evolutionary, biological imperative of competing for a mate—a bit like displaying your intellectual plumage, as it were.

Image: ©Arnold Schönberg Centre, Vienna.