With the exception of Jonathan Swift’s work, satire tends to be short-lived, depending as it does on criticism of its day’s cultural, political or social mores. I venture a guess that works like Vlad Mezrich’s Twilight satire, The Vampire is Just Not That Into You, will be read until the vampire craze is over and probably not a moment longer. More closely aligned with Swift’s work, however, are three examples of gentle and not-so-gentle 20th-century satire that, thanks to the vigour of their prose, their humour and their style, will be read long after the culture to which they were responding has vanished or morphed beyond recognition.

Colors Insulting to Nature (2004) is Cintra Wilson’s novel about a young girl who wants only to be famous. Wilson is a writer of uncommon energy and her instinct to go straight for the least appetizing aspects of a fame-sick culture proves almost painful. Colors reads like a death cry from someone drowning in mass media. Wilson is unsparing of her heroine, Liza, as demonstrated in this description of her audition for a role in a TV commercial: “The child took the microphone and Cher-ishly flipped back a strand of zigzag crimped hair with fuschia fingernails as the pianist rolled into the opening bars. Her vibrato, though untrained (learned, most likely, by imitating ecstatic car commercials) was as tight, small, and regular as the teeth on pinking sheers.” Liza, who is afflicted with very modest talent, a show business mother and suspect judgment, blunders and crashes her way into adulthood in a comic novel as sharp and unforgettable as any written in the last generation.

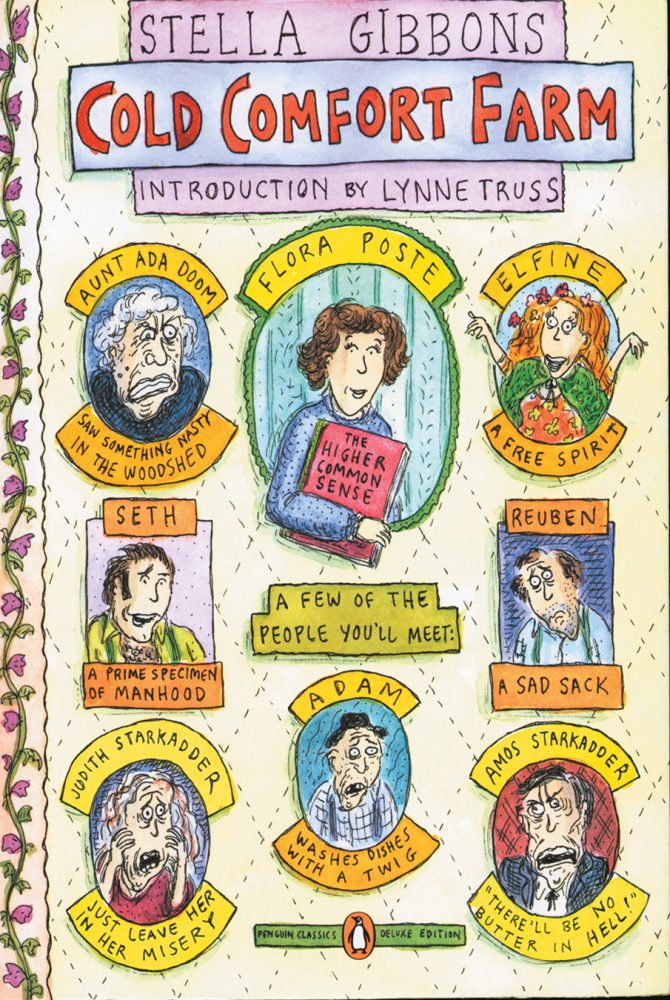

Another noteworthy satire, which has already demonstrated its staying power, is Stella Gibbons’s landmark Cold Comfort Farm (1932). Penguin has just released a new edition with front and back cover illustrations by The New Yorker’s Roz Chast, featuring portraits of Flora, the book’s ultra-efficient protagonist, as well as many of the other cast members, including the cows, Feckless, Graceless, Aimless and Pointless. In this story of a young woman who inherits a ramshackle old farm and briskly whips everyone and everything into shape, Gibbons was satirizing D.H. Lawrence’s sexual values, which dominated the literary world at the time, and took aim at the highly romanticized world of the English rural novel. Gibbons’s skewering of rural romance and her penchant for literary allusion make Cold Comfort Farm a bountiful playground for literary types.

Speaking of satire and literary types, William Kotzwinkle’s The Bear Went Over the Mountain (1996) conflates these two in a marvelous romp about a bear who discovers a manuscript hidden in the woods by a depressive professor of literature on sabbatical. Since Professor Arthur Bramhall’s first manuscript burned along with his house, he is very careful to put his rewrite in a briefcase and to stash it in a safe place. Safe, that is, from all but bears. The bear, like Professor Bramhall, is “a decent, hardworking sort” who has recently broken into a restaurant and developed a taste for human treats. When he discovers the manuscript, he thinks it is termite food, “but a line on the first page caught his eye and he read a little ways. His reading habits had been confined to the labels on jam jars and cans of colored sprinkles, but something in the manuscript compelled him to read further. ‘Why,’ he said to himself, ‘this isn’t bad at all.’ There was lots of sex and a good bit of fishing, whose details he thought were accurate and evocative. ‘This book has everything,’ he concluded.” Thus the bear, who assumes the nom de plume “Hal Jam”, finds a New York agent to represent the manuscript. The agent, charmed by Hal’s understated ways (“‘My god,’ thought Boykins, ‘he is another Hemingway.’”), lands the bear a blockbuster book deal. Professor Bramhall’s struggles to get his book back and Hal Jam’s rise to literary stardom constitute a scathing satire of publishing, the literary life and the modern condition. But the novel’s strange hilarity offers something of a salve for anyone who has ever wondered why some books become bestsellers and some get left to molder under trees.