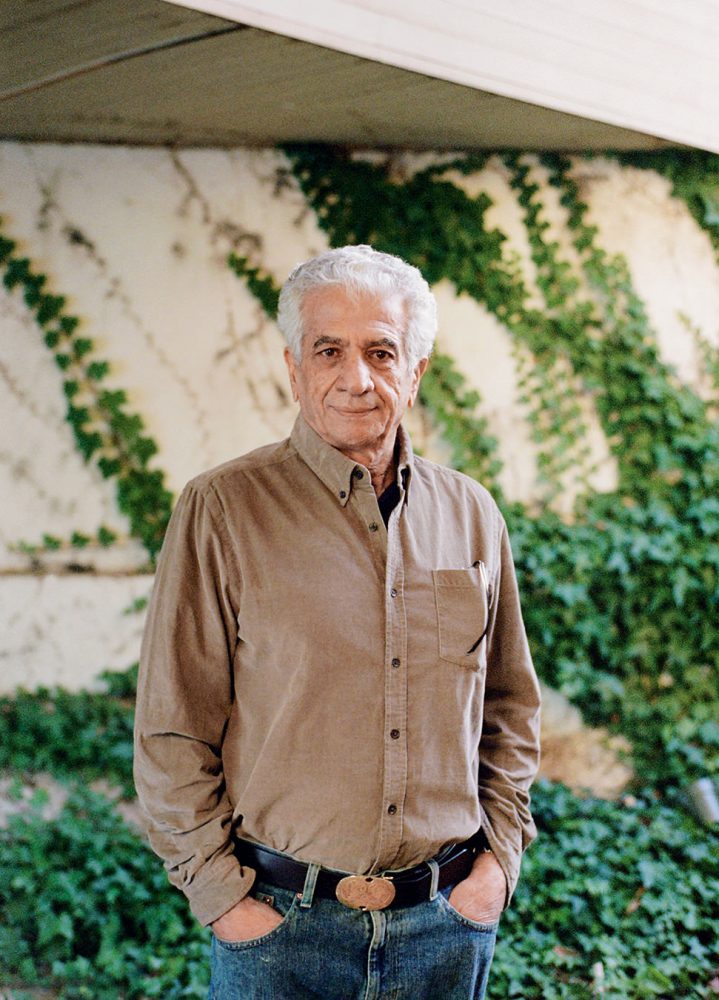

From his gentle handshake, one would never guess that Parviz Tanavoli’s hands have birthed more than 1,000 sculptures. He is now 75 years old, and his creations (some ceramic, most in bronze, with an occasional painting, too) have made appearances in some of the most prestigious venues in the world including the British Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the Royal Museum of Jordan, and dozens of others. He has lived in Vancouver for 24 years, and his art will now finally be showcased in his hometown as part of the Safar/Voyage exhibition at the Museum of Anthropology (MOA) at the University of British Columbia. “I am honoured to be part of this exhibition,” Tanavoli says as he sits comfortably in his West Vancouver home, the mountains providing a backdrop through his floor-to-ceiling windows, and a steaming glass of Iranian tea nestled gently in his hands. “My art has been in Canada before in a personal exhibition, but this one is much more important because for the first time I am with other artists from the Middle East in Vancouver.”

Set to open in April 2013, the Safar/Voyage exhibition will showcase 16 esteemed artists from the Middle East who express themselves through painting, performance, and sculpture. Their works, which are reflections on themes such as migration, war, geopolitics, and aesthetics, will span two galleries, covering more than 8,000 square feet. “It’s the largest and most complex exhibition we’ve ever done,” says Jill Baird, the curator of education and public programs for MOA since 1997. “It’s not an exhibition simply of artists from the Middle East, but instead, of artists that can provide some insight about where they come from and how this is relevant, even to people who are not from the communities they are from. It’s about having the artists show us things about themselves, and ourselves, at the same time.”

When the planning began in 2010, Tanavoli was invited to join the committee as a voice of knowledge about Middle Eastern art and artists. Fereshteh Daftari, formerly of the Museum of Modern Art in New York and a respected expert of Middle Eastern art, was brought onboard as a guest curator of Safar/Voyage. “Instead of a narrow vision of art by artists from a Middle Eastern origin revolving around traditional calligraphy and veiled women, the exhibition delves into the multi-faceted ideas of voyage ranging from border crossing, war, migration, and exile to philosophical positions regarding life itself as a voyage,” she explains.

Daftari arrived at the list of artists and works; as members of the external exhibition committee, Tavavoli and Baird were part of the approval process. But Tanavoli also contributed many ideas from the outset of the process. “Tanavoli is the ideal artist to work with—a mine of information, generous with his time, respectful of your ideas, and a great personality,” Daftari says. “He is a towering figure in Iranian modern art and significantly active to this day.”

As Daftari and Baird built the list of artists for the exhibition, it became obvious that Tanavoli’s art was a strong match for its theme. Daftari chose Oh Persepolis II from his repertoire after seeing it in Parviz’s studio in Tehran. It was shipped to the museum from there. “We were like kids in a candy store when we opened that crate,” says Baird. “It just glows.”

“I like to work on the surface of my art. I like to write on them, I like to open up holes in the body of my sculptures; I like to show the inside. Bronze is perfect for that.”

Oh Persepolis II is a stunning bronze wall weighing 1.5 tonnes and standing over six feet tall, its surface raised with detailed characters reminiscent of Persian cuneiform. “This sculpture is meant to capture the essence of an amazing example of Iranian culture and heritage,” says Tanavoli, explaining more about the ancient site in Iran that was once the ceremonial capital of an Iranian empire. “It represents a time when Iran was vibrant and alive. It was one of the most advanced nations of the world,” he adds, clearing his throat as emotion takes over. “I feel sad about where the country is now. I studied in Milan and in Carrara, and then was teaching as head of the sculpting department at Tehran University until the revolution. Then my studio was closed and sculpting was not allowed. I came to Canada and continued. I’ve been living and working here, and exhibiting elsewhere. But this is changing also; this upcoming exhibit at the MOA is a great, great step.”

Born and raised in Iran, Tanavoli discovered his passion for sculpture in his early teens. “No one in my family is an artist,” he says, remembering how his parents supported him. He was the first to register for and graduate from the school of sculpture in Iran. As his talent grew, so did his interest in working with different materials. “When I went to school in Italy, I was introduced to bronze casting, which became my favourite,” Tanavoli explains. “I like to work on the surface of my art. I like to write on them or make holes, and for this, bronze is the perfect material. I like to open up holes in the body of my sculptures; I like to show the inside. Bronze is perfect for that.”

Mistakes are costly when working with bronze. It costs tens of thousands of dollars to make one of the larger sculptures. “I have taken several years on a single piece before,” he says, adding that he is no rush to give birth to his inspirations. “Sometimes you get stuck and you need time. With 50 years of experience, you almost cannot make a mistake. You know if something is not working; if it is not, I have no doubt. I have to be happy, satisfied, so I may change it until I like it. Sometimes it takes longer, sometimes shorter. It goes on until it’s finished, but I always know it will be done.”

When stuck, Tanavoli leaves his art and delves into the art of others. He walks in nature. He listens to music and, most often, reads the works of the Persian-Muslim poet Jalaluddin Rumi. “For me, Rumi is everything,” he says. “I can live with his poems for days and days, and I need no other inspiration because to me he is the master of our universe. I have learned more from him than from all my formal schooling, both in Iran and in the West. He has said it all about human attitudes and human feelings. He is very optimistic, and I like optimism.” Tanavoli’s love for Rumi began at a young age and inspired many of his sculptures. “When I was in Italy, all by myself, a very young student and very lonely, I had taken a book of Rumi’s with me, and anytime I got homesick, I read it and I got energetic. From one poem, I felt like I could carve a mountain! He consoled me.”

By age 22, Tanavoli was invited to some of the world’s largest art exhibitions in Paris, Venice, and Carrara. “Because my art was so different than other artists’, more museums bought my art and more exposure happened. It took me years and years to make my mark,” he says.

“My main theme is poets. … In the chest of the poet is a cage. In this cage there is a nightingale, which keeps singing, keeps living, and that’s what makes the poet so creative. Even if the cage is locked up, it sings.”

Throughout his career he took many leaps of faith. “When I moved with my family to Vancouver in 1989 and started fresh, I continued to make these sculptures, and it was very difficult financially,” remembers Tanavoli. “I was at the point of going bankrupt many times, and just when I was despairing and I began to believe everything would collapse in my life, something amazing would happen. Some of the wealthy Iranians who also had to leave Iran did not forget me or my art.” They encouraged Tanavoli by purchasing his sculptures and inviting him to London, Paris, and New York to meet with other artists.

He kept true to his vision. “I have built a world of my own, and I am living in that world. My main theme is poets; sometimes alone, sometimes with the beloved. In the chest of the poet is a cage. In this cage there is a nightingale, which keeps singing, keeps living, and that’s what makes the poet so creative. Even if the cage is locked up, it sings.” Over time, he found his feet again. “I believe in miracles,” he says with a smile. “You cannot get scared at the beginning,” he says, referring to the fearlessness a young artist needs. “You just have to create and then allow the other solutions to come later. You have better control of a smaller piece. A larger piece, it can be larger than you, so you have to move around it, you cannot see it all at once.” He laughs as he remembers a sculpture that got out of hand. “It was so big I could not get it out of the studio and I had to cut the roof off to take it out!”

He looks around his living room, pauses, and says, “I don’t explain my sculptures, because for one thing it is difficult to explain something like this, at least in general terms. But I have certain ideas. The body of the poet, I like to build it architecturally, so it becomes a blend of the architecture and the human, and these become windows into each other. I think about the poet, his imagination, and how he can express something, and I think about this as I use architectural ideas in my sculptures.” He pauses, and adds the most important part: “I don’t write about it, or talk about it very much. I let people decide for themselves, to look at a sculpture and have their own definition, have their own inspiration.”

Today, Tanavoli spends his time between Tehran and Vancouver, and he has a studio in both places. “I am so blessed because the time I spend in my studio is the best time of my life,” he says, his voice filled with purpose. “I miss it to an extent that if I am in Mexico or Hawaii or Las Vegas, after a day or two, I really want to fly back and get to the studio.” There is a pause in the conversation, and Tanavoli sits quietly, comfortable with the silence. Finally, he adds, “It is who I am. I cannot change this, and I would never want to.”