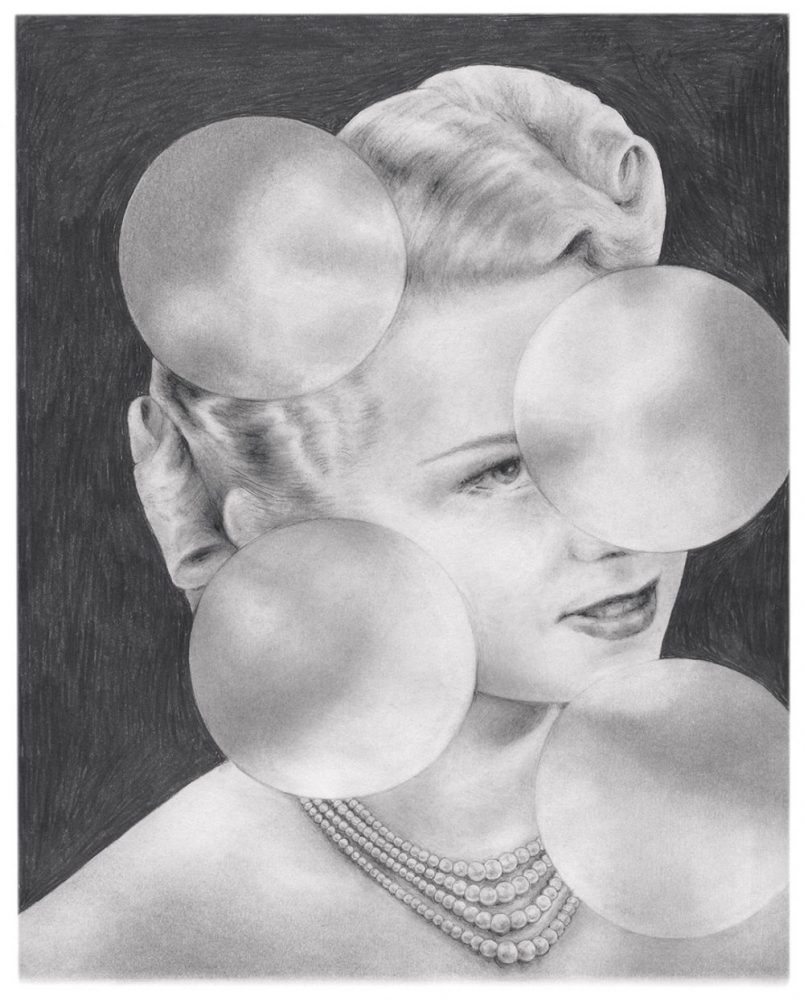

“At dinner parties, people would ask me, ‘Well, what do you do?’ I would stammer and awkwardly search for something to say,” Carol Newell says, as the afternoon sun began peeking through the fifth floor window of her Gastown office in the revitalized Flack Block building. “Someone said to me that I should practise on taxi drivers. Now I just say that I’m a private investor, but at that time, I didn’t want anyone to know I had money to invest,” she adds as we begin to discuss her path from anonymous donor to public philanthropist. Newell is the heir of a multi-million dollar inheritance, and her personal story of giving is reflective of how today’s young philanthropists come to terms with newfound wealth and learn to activate their capital for social good. It was only after more than a decade following her initial philanthropic work that she made public her anonymous contributions through her now-retired Endswell Foundation. “In many ways, anonymity can be very difficult, because you are always holding something back,” Newell says. “It wasn’t until I was in my 40s that I came out about my wealth. Until then, I was a woman walking around with a secret.”

Newell was only nine years old when her father passed away, leaving her mother, then 47, to boldly transform from housewife to company director of the Newell Companies, the housewares manufacturer where her father had been CFO. “She literally took that responsibility, on the board,” recalls Newell, remembering her mother learning to guide what would become, in the 1990s, NewellRubbermaid, a Fortune 500 company. She was a forerunner—a woman holding a board seat in the 1960s. Newell watched and learned from her mother some of the basics, from financial management, to bringing in the right advisors. “She would come to me and ask, ‘Well, what do you think, Carol?’ I was 18 years old.” It was with great foresight that she did this, because when Newell was 21 and after she received her first inheritance, her mother suffered a heart attack, forcing Newell to manage her mother’s personal finances. She had learned enough about finance and managing their family’s responsibilities that for half a year she was able to manage in her mother’s place.

Following her mother’s passing, Newell, at 36, had to assess her situation, and decide what to do next. With a personal inheritance totalling $30-million (which grew to $76-million by the mid-nineties through a planned divestiture and reinvestment strategy), Newell knew that she had enough wealth for herself. She immediately began to seek ways to mindfully and deliberately allocate her capital in ways that were meaningful to her. She felt a deep responsibility to deploy her resources in ways that blended her wealth and values, often reminding herself that “my money is at work, wherever it is, so what do I want it working on?” It was around this time, in the late eighties, that Newell moved, first to Vermont for 18 months, then to B.C. After dozens of quiet philanthropic efforts in environment and social justice with organizations like the Sage Foundation, Destination Conservation, Tides Canada, the Dogwood Initiative, and the Hollyhock Leadership Institute, among others, she “came out” about her giving in 2002.

When you begin to talk about the motivations behind anonymous giving, you venture into a “kaleidoscope of stories and issues,” according to Sheherazade Hirji, vice president of client services at Tides Canada. Tides is a national Vancouver- and Toronto-based philanthropic foundation focused on environmental and social issues, and it was Endswell’s largest donor advised fund as well as a significant beneficiary. Having worked with a large number of anonymous donors over her 22 years in the philanthropic sector, Hirji has had varied experiences that lend colour to these diverse stories. One female donor she worked with did not want her contribution to an organization to overshadow her active role on their board and create an imbalance of power. Through her anonymous gift, she equalized the dialogue around the boardroom table while still contributing in a significant way. The challenges Hirji points out in this case are that the organization never knew they could ask this donor for more, and the recipients were left to speculate about the donor’s motivations and intentions.

It is hard to generalize about these quiet givers. Their impact and identities are distributed across a variety of organizations, roles, and geographies, and as such, it’s nearly impossible to understand their true intent or full impact. Despite this, their invisible contributions can be incredibly transformative, so much so that it could be argued that whether we know it or not, we’ve all been touched in some way by the selfless contributions of anonymous philanthropy.

In a 1991 study on anonymous giving, the Center on Philanthropy at the University of Indiana, found that approximately 50 per cent of the anonymous donors surveyed choose to do so because they did not want to be solicited. They want to purposefully give without having their philanthropy determined by the demands of the loudest and most aggressive cause-driven organizations. The next most cited reason according to the study was spiritually based giving. Hirji says that for her donors who are guided by religious or spiritual beliefs, anonymous giving is often seen as the highest form of giving. Many denominations make giving a regular part of their religious practice. Their adherents don’t consider themselves philanthropists per se; instead, they derive spiritual satisfaction from their acts of giving that go far beyond recognition and legacy. She notes that “many donors give anonymously to protect their privacy and to avoid being solicited by a large number of charities once their generosity becomes known.

Stories of reclusive donors are always fraught with interest. Bill Gates and Warren Buffett have started the Giving Pledge, an invitation to wealthy individuals to commit the majority of their wealth to philanthropy and charity, either during their lifetimes or after their deaths. They have convinced the likes of Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg and over 90 other billionaires to commit a large portion of their fortunes to charity as part of the Giving Pledge. There is even ongoing speculation that Apple’s late visionary, Steve Jobs, was a shrewd anonymous donor. Upon his death, the allocation of his estimated $6.7-billion estate will remain as private as the enigmatic CEO was. But theories swirled in 2009 when Jobs’ name came up associated with a $150-million donation to the Helen Diller Family Comprehensive Cancer Center at the University of California in San Francisco. Officials with the hospital denied he was responsible for the gift, but the rumours still remain.

In our own community, 2012 saw two significant anonymous gifts made available to the City of Vancouver totalling over $40-million. An anonymous couple put forward $30-million to reopen and operate the Taylor Manor long-term care facility to support the homeless and mentally ill, and a different donor offered $10-million to complete a proposed expansion of the seawall from Kitsilano to Jericho Park. When asked about the gifts in an interview with The Vancouver Courier, Vancouver Foundation president and CEO Faye Wightman publically expressed hope that these gifts could inspire other anonymous donors to give. Less than one per cent of her foundation’s gifts were given anonymously at the time.

For Newell and other anonymous givers, their work is not driven by ego, but rather, by conviction. “Depending on who you are and what you are trying to accomplish, the anonymity can be a great gift to yourself, because in many ways it’s easier,” she says. “You don’t get put on a stage, you don’t get put in front of a firing squad, you don’t get people treating you differently. There’s a great, deep satisfaction.” Anonymous giving has a magical feeling. Selfless, unrecognized philanthropic work offers “a little secret spark, which nobody knows but you” and an “intangible quality that can be very nourishing.” With an increasing public awareness of the high concentrations of wealth growing in the hands of the few, anonymous giving offers something special for those with means. We often think of wealth in pragmatic terms; however, at some point a greater rate of return comes when we invest in exploring solutions to important problems we never dreamed of solving but always knew there were answers for.