There’s something sitting on top of the credenza behind Dr. Ralph Buttyan. Hard to see what it is, exactly. A sculpture, perhaps; maybe a carving. A little smaller than a football and grey brown in colour. Buttyan is sitting in front, fully engrossed in the conversation, making his points with emphasis, communicating his passion and his intellect with every gesture of his hands.

When asked about it, he turns around. “Oh, that—a gypsum crystal from the Arizona desert.” A pattern of beautiful crystal petals, blossoming along a ridge of rock like the spine of some magical creature. “It’s natural beauty,” Buttyan says in a soft voice, holding the rock delicately in his hands. “These minerals—they’re fantastic. It’s fascinating the way nature works.”

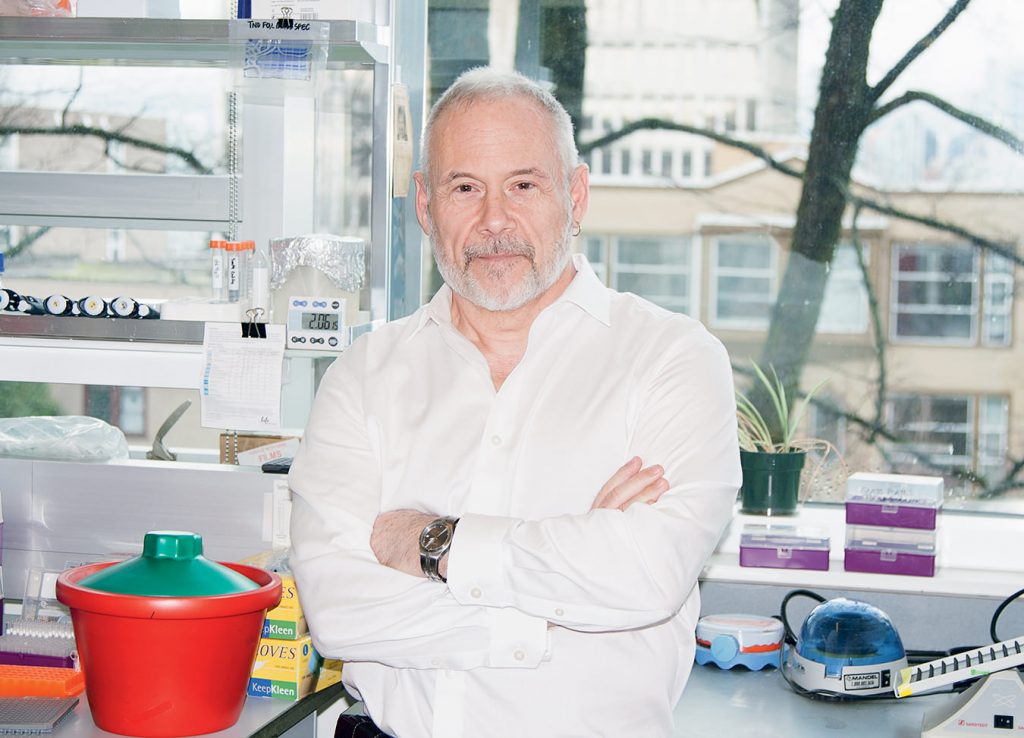

It’s a fitting parallel with Buttyan’s nine-to-five. As a senior research scientist at the Vancouver Prostate Centre, Buttyan is responsible for leading a nationwide team developing long-term treatments for prostate cancer, one of the leading causes of death among Canadian males. Serious stuff, to be sure. But it’s impossible not to notice that same sense of childlike wonder and reverence, that deep and penetrating curiosity about the way Nature works—and the way she keeps her secrets. “It’s really an amazing subject to me,” Buttyan says with an infectious energy. “The idea that this cancer cell is dependent on the male steroids—what is the basis of this dependence? How does it overcome this dependence? What can I do to target this independent state?”

Buttyan’s specific area of research is tumour plasticity; in lay terms, the ability of cancer cells to evade therapy and resist drugs via a series of genetic mutations and molecular adaptations. “We’re finding that as prostate cancer gets worse, it’s basically regressing back to a stem cell–like state,” he explains. “This gives it a lot of flexibility, because if you hit it now with a therapy, it can go into developmental pathways that may help it escape. So what we want to do now is prevent it from going into that stem cell–like state by blocking these developmental pathways.”

Such lofty goals demand a team-based, multidisciplinary approach. Instead of locking himself in his lab, Buttyan works with the pathologist who knows the disease inside out, the chemist working to develop an entirely new class of drugs, the oncology specialist who understands the effect of this or that therapy on the patient, and so on. This, ultimately, may be the scientist’s most powerful tool of all—that by assembling a team that works via daily collaboration rather than an “every man for himself” competition, out-of-the-box thinking becomes the norm and breakthrough ideas come faster.

“Patients are being treated better. They are receiving treatments more tailored to their specific disease state, and because of this, survival from late-stage disease is improving significantly.”

“If you’re just approaching the problem from one angle, it could work or it couldn’t work,” Buttyan remarks. “Now, essentially what we have is five smaller teams, and each one is looking at a different aspect of this adaption. So the chances of us getting something successful, meaning a treatment, out of this are much higher.”

Even so, Buttyan is careful to temper his optimism. He avoids the kinds of martial metaphors that often define cancer research; in the context of prostate cancer, trying to “win the battle”, “fight the fight”, or “conquer the disease” doesn’t make much sense. “I will not talk about cures,” Buttyan says bluntly. “Our realization is that you probably won’t cure this thing. And that’s because just like HIV, cancer cells go into dormancy. They can hide, and then they can re-emerge at some point later with an aggressive phenotype.”

But as Buttyan explains, that’s not necessarily a bad thing. “Most patients are in their late 50s, 60s, 70s. Can we keep them going for 20 to 25 years, and then they’ll die of something else? That’s one of the goals of treatment. We will feel successful if we can maintain cancer in this dormancy throughout the life of the patient by taking a few drugs. That’s what we’ve all tagged our hopes on right now.”

The plausibility of reaching that goal? “Very, very high,” Buttyan says without hesitation. He leans forward in his chair again, re-engaged and reinvigorated. “There are new drugs being introduced. Deaths from prostate cancer are declining. We have the best and most reliable test for cancer in prostate cancer—absolutely the best early detection test in all of the tumour systems, the blood-based prostate-specific antigen test. Also, patients are being treated better. They are receiving treatments more tailored to their specific disease state, and because of this, survival from late-stage disease is improving significantly.” No, you can’t see the crystal behind him. But you can almost feel the petals bristle with energy.