“My existence,” Nicole Brossard has said, “is a walk in writing.” It’s a fitting metaphor for the essential confluence of body and text that comprises the life of this prolific, versatile, and challenging writer. It is hard to label someone whose identity is insistently fluid, performative, and provisional: poet, novelist, essayist, dramatist, editor, public intellectual; or francophone, feminist, advocate, activist, avant-gardist. All fit Brossard, who has published over 30 collections of poetry and a dozen novels, among other works. A Montrealer by birth and temperament, she is one of Canada’s most honoured and respected writers, known widely in the French-speaking world but increasingly by those reading her work in translation.

I ask Brossard whether translation might be a useful metaphor for her work in general, in terms of not just the semantic leaps and syntactic gaps in her writing that necessitate some form of translation on the reader’s part but also the writer’s prior negotiation of the inescapable yet creative gaps between life and art, white space and inked space. “Translation is a vital metaphor in my writing,” Brossard says, “but probably as well in my life, in the sense that meaning is never safe or definite. We are always translating each other, even when we speak the same language.”

Being comfortable with complexity and uncertainty, is at times vertiginous but ultimately exhilarating—an encounter with a writer whose work is still in progress but who has already achieved an oeuvre and a recognition well deserved.

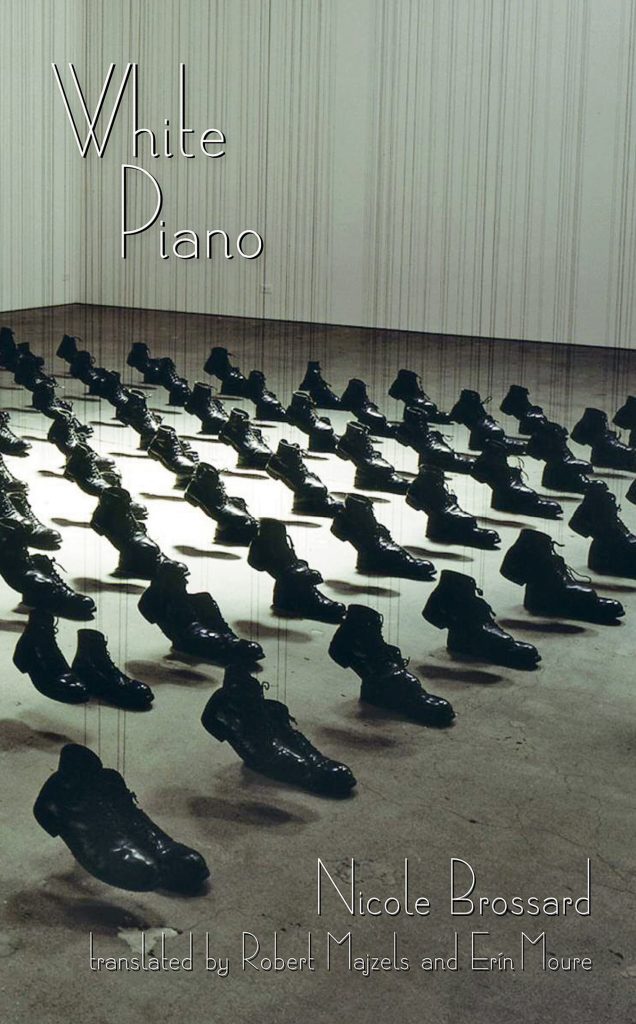

A good introduction to Brossard’s poetry and prose in English translations is Selections (2010), an anthology of her work from 1968 to 2008 selected by Brossard herself; Mauve Desert (1990), a novel within a novel that reflects her innovative fiction; and Notebook of Roses and Civilization (2007), a finalist for the Griffin Poetry Prize. Yet in spite of her generic range, poetry remains her signature medium. Her most recent volume of poems, White Piano (2013), extends her improvisations on an image that detonates forcefully in her imagination and throughout her work. “My motivation for writing is exploration, discovery about oneself maybe, but mostly about life in its vibrant, tiny processes of continuous transformation of meaning,” she says. “Language gives pleasure because it is highly interactive and transformative. It is because writing forces us to slow down, reread, erase, displace differently, it creates viable spaces in which we can breathe and think differently. Poetry matters because, in a way, it creates the best territories of thought and emotion from which to look at the world, to inhabit it, or simply to be.”

Brossard has used many terms to define her writing: playful (with words), experimental (with forms), exploratory (with ideas), subversive and celebratory (of the body and of language). But for all its adventurousness, her writing is grounded in fundamental human issues and a concern that each individual be a contemporary subject, whole and free, which for her means “not only understanding life in general but understanding the very specific moment where life, truth, and reality transform our human certitudes about the world, the universe, and the images constructed to define our species. To be free means to own your own body, to decide your actions, to love or associate with whomever you choose, to express publicly your thoughts on the organized society in which you live without fear of being intimidated or arrested, and finally to make sure that your private life is not under surveillance or sold as a product. What is at stake is what we have called until now the human condition, our ‘humanity’ as we have known it and mostly as we have defined it.”

According to Brossard, her ideal reader “vibrates to language and to the effort we—writers and readers—make to translate the inexpressible in us caught between the human condition and the intuition of a more transcendental one. For me, the ideal reader is a companion sharing the vibration of what is really at stake with the words on the page, in this paragraph, in the line.” Letting Brossard’s words, their connotations, and their associations take your mind in new directions to unexpected places, pacing your comprehension with the rhythm and spacing of the phrases, being comfortable with complexity and uncertainty, is at times vertiginous but ultimately exhilarating—an encounter with a writer whose work is still in progress but who has already achieved an oeuvre and a recognition well deserved.