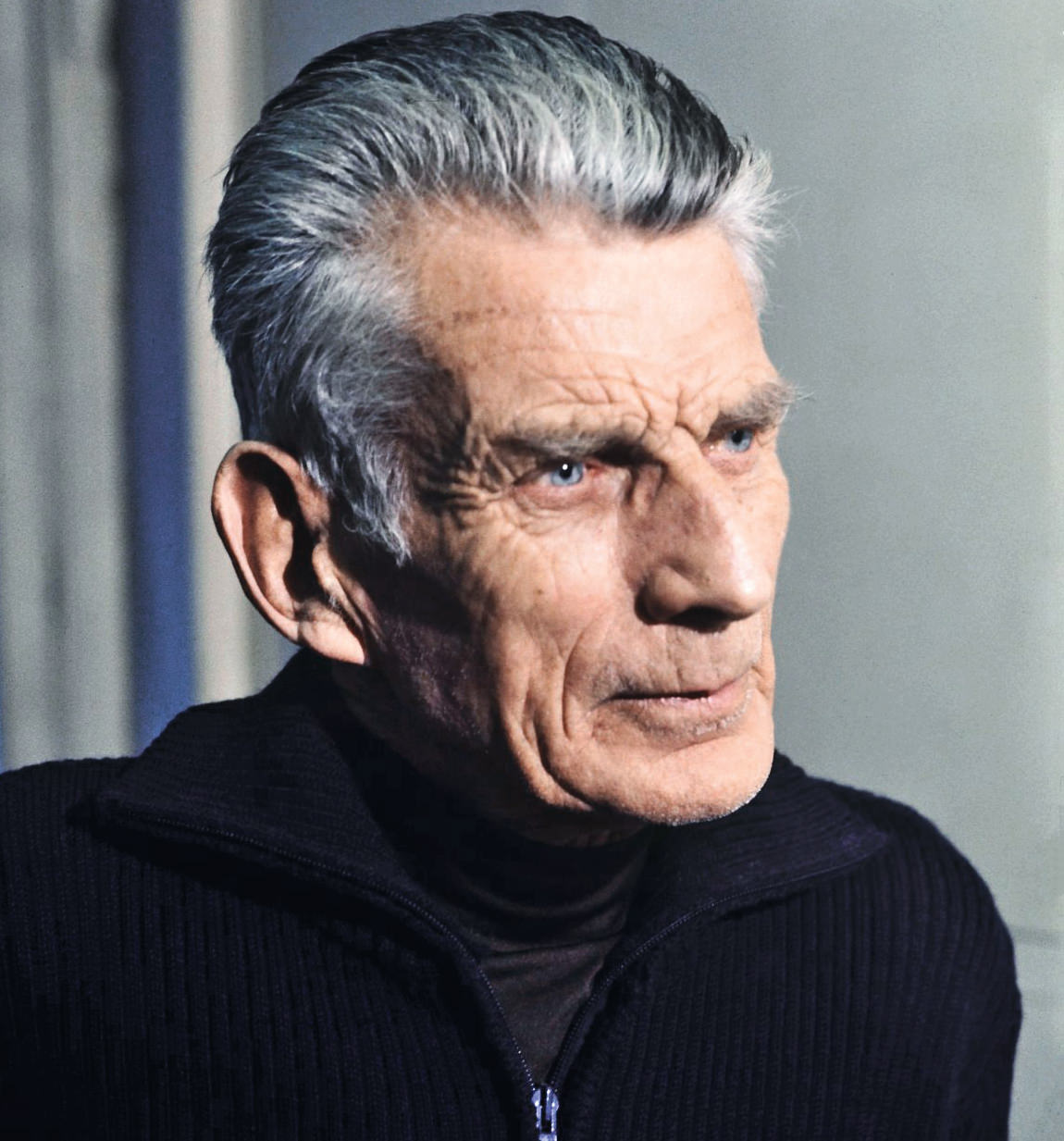

Samuel Beckett was one of the great literary Modernists. As novelist, playwright, director, poet, critic, Nobel Prize winner, Beckett achieved an immense stature and has been enormously influential, yet he is not as widely read by a general audience as he might be, partly because of his minimalist style, his pessimism, and the seeming obscurity of his ideas.

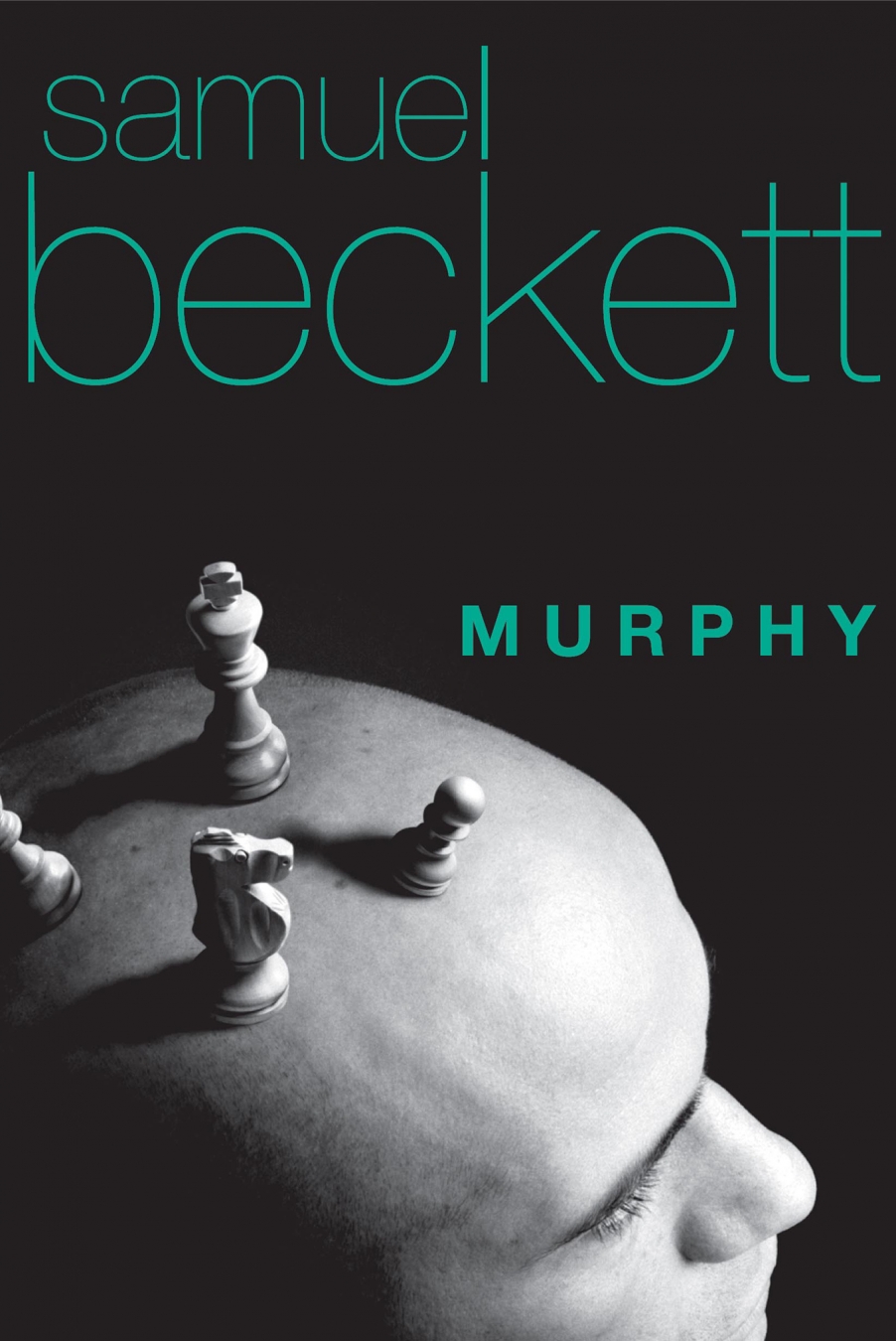

However, Beckett is approachable, and his first novel, Murphy, is a comic masterpiece, an uncommon though not unique combination of philosophical density and hilarious characters and events. Beckett uses the conventions of the traditional novel but parodies and subverts them: here, boy meets girl and needs a job in order to settle down, complicated by the obligatory triangle—not one in this case but several overlapping ones—and by Murphy’s state of mind. Beckett’s narrative intrusions, commenting on characters and actions, help sustain an ironic distance, and many of the characters are caricatures, offspring of slapstick and farce, self-interested “puppets” according to the narrator, though Murphy (the commonness of the name in Ireland, where most of the characters originate, lends him exemplary stature) is clearly more substantial, as are Neary, a would-be philosopher, who moves beyond mere self-interest to empathy and compassion, and Celia, where the clichéd prostitute with heart of gold is actually one whose love is genuine, as are her loss and suffering.

Propelling the action and its crises is the dominant philosophical tradition of Western culture, from its classical and Christian roots to contemporary thought: the Logos as the principle of order and harmony in the universe and reason as the highest point of consciousness. Pivotal is Descartes, often considered the father of modern Western philosophy, with his rational, inductive methodology and the dualism that results: the mind conscious of itself and all that is external to it.

The novel interrogates this tradition and the dualisms of mind and body, inner and outer, self and other. Murphy attempts to ease his irrational heart by distancing himself from an entanglement with one woman by leaving Ireland for London, only to become involved in another, more serious relationship. This establishes the main plot—Murphy’s ostensible search for a job and his actual search for an ideal state of being—and a parallel plot, the search for Murphy by those he abandoned in Ireland.

Murphy structures his experience in Cartesian terms, body and mind, the big world outside, to which he is willing to make only small concessions, and the little world within, a closed, self-sufficient system where he can be wholly and freely himself. The obstacle is Celia, representing the inescapable life of the body, and Murphy’s desire for her threatens his sense of self. His carefully circumvented job search ends at a mental hospital, attending to people he regards as kindred spirits, at home in their own closed worlds, the only work site Murphy finds suitable, and the site as well of his chaotic “misadventure”.

The novel challenges the systems used to order and control experience, including science, mathematics, religion, astrology, even language itself, and Beckett’s comic vision is rooted in the absurdity of trying to behave rationally, logically in a non-Newtonian universe, where unconscious and subconscious depths of being disrupt surface reality, where systems of order are imposed rather than inherent—arbitrary, limited by chance and the irrational, and attempts to renounce or transcend such a world prove futile.

Beckett’s language ranges from arcane vocabulary to slang; and puns—some painfully obvious, some so erudite as almost to evade detection—are pervasive and thematically pertinent, offering a multiplicity of meanings, ambiguous, irreconcilable. A central one is the heroine’s name, Celia, suggesting both heaven (French: ciel), a transcendent goal, and s’il y a, pondering “if there is” such a possibility. Beckett was a master of allusion, complex, often ironic and multilayered, so that the text becomes a kind of palimpsest and reading an archeological excavation of meanings. The more equipped a reader is with literary and philosophical tools or even just with critical thinking skills, the richer the findings. But like other good writers, Beckett makes most allusions work on the surface level as well, naturalized in the immediate context so that any reader can access the pleasures of the text, “such pleasure,” as the narrator says, “that pleasure [is] not the word”.