Being in culture is to be formed by culture. Also, being in culture is to contribute to its formation. The individual and their social context are in a dance of mutual becoming, a process of entwined creation that ranges from the banal to the extraordinary. Recent films made by black women are shifting representations of gender, sexuality, and race in ways that highlight the vital role their perspectives play in these ongoing cultural evolutions.

Hannah Black’s My Bodies (2014) is a short experimental video that begins with a chorus of women’s voices proclaiming “my body” over a progression of closely-cropped headshots of men, focusing in on their smiling mouths. The proclamations have been mixed together from R&B songs, a lyrical survey of different intonations of claiming one’s self. The images are of white men wearing suits and ties, performing the look of power in caricatured ways. The implication is that these men, as many different embodiments of a certain archetype, could use their status to counter the claim the women are making. (Think: American senators legislating access to birth control.) In the second act, dripping wet, cave-like spaces illustrate a karaoke-ready version of Ciara’s “Body Party”, though the lyric tape has been replaced by a poetic rumination on reincarnation: “you will be translated back into yourself and back… / you will hesitate at the gate of the world asking ‘what will become of me’ / ‘girl, try your luck, every birth…is a wager.’ ”

As a thought experiment, My Bodies proposes a choice of becoming: at the precipice of entering flesh again and knowing what they know about being a woman in the world today, would these voices choose to come back female? What is gender when we make of it what we will? The title of Black’s work, in the plural, suggests that to be in a body is always a negotiation between expectation and desire, between social pressures and a sense of self. Identity arises from a reconciliation of these forces, however tenuous or fraught it may be, where each proclamation of “my body” is particular and subject to change.

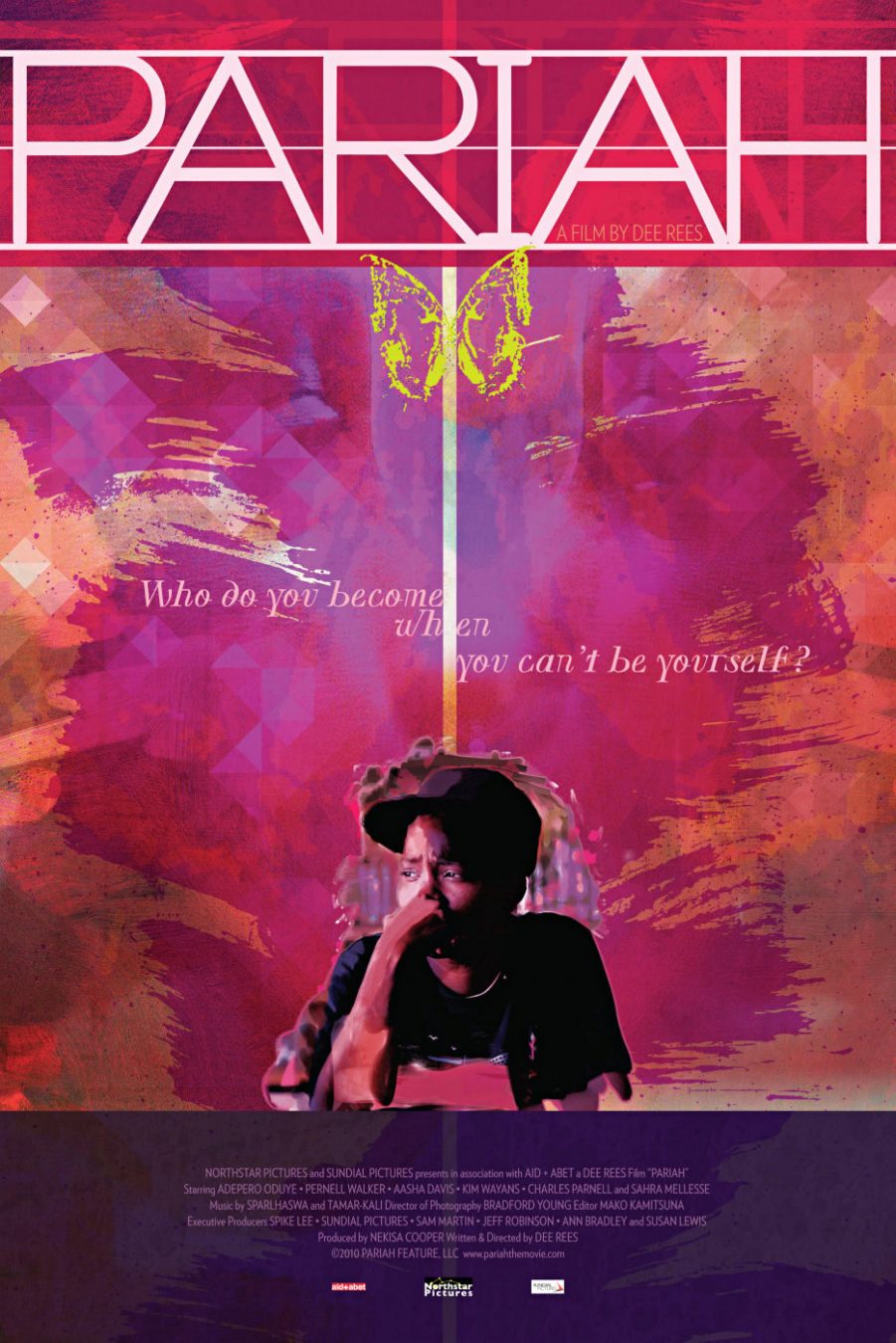

In Dee Rees’s Pariah (2011), the 17-year-old protagonist, Alike, is comfortable with her lesbian identity and yet unsure of where she fits along a spectrum of queer performativity. At home, under the intense pressure of her mother’s denial of her sexuality, Alike veers toward the feminine. At gay bars, as she begins to perceive herself as a lesbian, Alike veers toward the butch instead. But Pariah is not a film about the negotiation of identity so much as it is about the obligation that a sense of self entails. As her parents’ refusals to accept Alike’s sexuality becomes increasingly cruel and absurd, her coming of age is brought about through her rejection of their denial: Alike grants herself freedom from their control and in that space of not knowing what comes next, she is empowered. As she prepares for a different life, Alike makes sense of her transition through writing: “…I am not running / I’m choosing / Running is not a choice from the breaking / Breaking is freeing / Broken is freedom / I am not broken / I’m free.”

Freedom is this self-articulation, this construction of possibility for what is to come. Considering that Pariah is a film about being a black lesbian made by a black lesbian, it is important to recognize how utterly rare this perspective is within the mainstream film industry. By refusing a continued neglect of black queer subjectivity in popular film and rejecting a system of being spoken for, Rees’s film makes and takes up space in a way that undoes marginalization.

Ava DuVernay’s Selma (2014) is another powerful example of what it looks like when people tell their own stories rather than having those stories told for them. The film chronicles events surrounding the 1965 voting rights marches in Alabama, which were characterized by the brutality of the white police state against unarmed black citizens. Focusing in on Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s role in organizing the protest actions, Selma reconstructs a pivotal moment in the civil rights movement while posing a question about what history is. Much has been made of DuVernay’s creative license in making the film—unable to access the copyrighted speeches of Dr. King, all of his dialogue in the film has been skillfully reimagined; the role of women in the struggle has been highlighted; and many critics have made a fuss over the challenges posed to American history when articulated from a black perspective. Viewers are asked to acknowledge that history is always already an approximation; there is no such thing as strict correspondence. Selma also makes clear that history is not something that merely rolls along and happens to us. The cast of characters that stand alongside Dr. King changed America, just as Dr. King’s labour and sacrifices changed him. As it stands, the legislative equality insisted upon by Dr. King and those who protested alongside him continues to be contested and it is impossible to not see Selma through contemporary forms of systemic racism, the non-acquittals for the murders of Mike Brown and Eric Garner being just two recent examples.

These works express an urgency in their artistic self-articulations: they are claiming agency in constructions of identity and society. DuVernay, Rees, and Black create portraits of the world from their particular subject positions, insisting that their perspectives come to bear on the shared worlds we make together. Revolutions are a direct response to the way things are, in service of how else they could be, and the worlds these directors create emphasize the feminist black body and the expanded legibility of their desires. This is a redistribution of agency away from being spoken for and toward speaking for oneself.

Film stills and poster from Pariah (2011) from Focus Features.