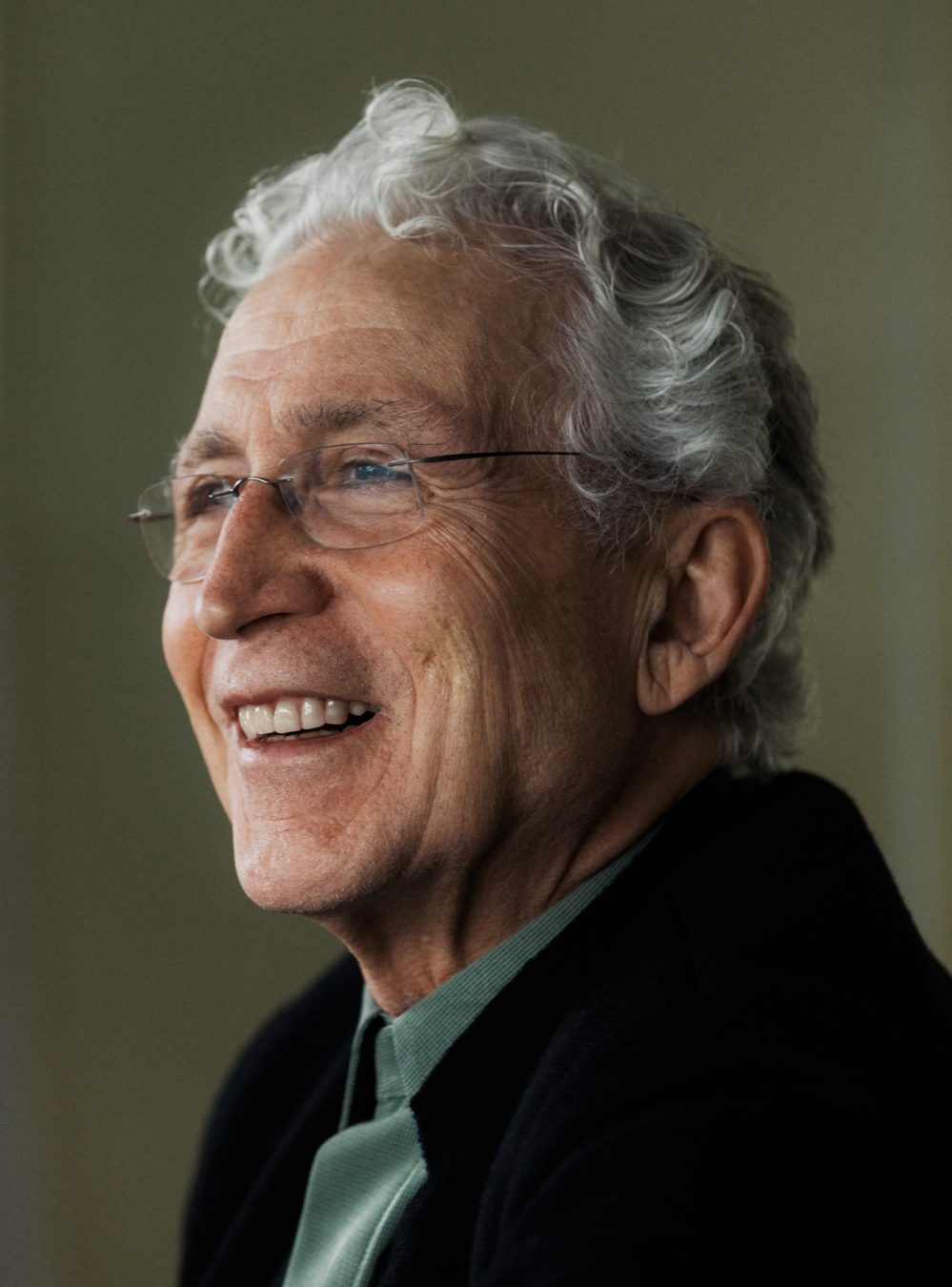

There is always a project in the works for Hossein Amanat. The 74-year-old architect shows no signs of slowing; his firm, Amanat Architect, has two condominium towers going up in New Westminster, as well as projects underway in Calgary, San Diego, Bellevue, and China. Construction has begun on a mixed residential and retail space for fashion label Zonda Nellis, slated to open this summer in South Granville. The site, which will feature beautifully painted concrete and glass panels, is only a short walk from Amanat’s own studio.

Amanat’s office building is what you would expect from a high-calibre architect: it’s LEED-certified, and recognized with a merit award from the Real Estate Board of Greater Vancouver. From the outside, the building’s façade—interplays of white, black, and touches of yellow on a chic glass grid—is reminiscent of a modern painting. Inside, the elegant foyer doubles as Gallery 1515, an exhibition space for contemporary art run by the architect’s daughter, Sarvenaz Amanat.

Beyond glass doors are the workstations: neat, but laden with a creative clutter of mock-ups and sketches stacked on every surface. A longer staircase rises up to a loft. Ascending it, visitors pass a large, striking canvas by artist Matt Sesow. And at the top of the steps is a boardroom, as well as a scale model of the firm’s Arc Complex at The Bahá’í World Centre: a complex of majestic, neoclassical buildings in Haifa, Israel. “They have aspects of traditional European architecture—Greek architecture,” Amanat says of the Arc. He is soft-spoken and dignified, yet has an easygoing air about him as he explains the Bahá’í buildings: “But the spaces inside are completely modern.”

Amanat is a practicing Bahá’í, one reason why he cannot return to his birthplace of Iran—religious persecution still poses a very real danger. Yet Amanat’s undeniable presence endures in his homeland, manifesting in the nation’s most iconic symbol: the Azadi Tower. The monolith, which is cladded with solid white marble and looms over Tehran from the west, is emblematic of Iran. It’s been a site of protests, civil rights demonstrations, and rallies—whether against the Shah of Iran or the Islamic republic—since its completion in 1971. In Farsi, “azadi” means “freedom.”

Amanat was only 24 years old when his concept for the Azadi Tower, then called the Shahyad monument, or King’s Memorial, won a design competition for a work commemorating 2,500 years of the Persian Empire. At that time, he was fresh out of architecture school at the University of Tehran, where his professors blended a Parisian, Beaux-Arts education with an appreciation of local architectural history. “We visited the old buildings in Iran and sketched them,” Amanat recalls. “And when you sketch a building, it’s like a meditation on that building. You see every corner of it.”

The design for the Azadi Tower was a natural synthesis of forms he had seen and studied. For instance: Amanat notes how the straight, level walls of the monument’s base curve into a concave dome at its centre, evoking a gateway. This transition from straight walls into a graceful circle, or what Amanat refers to as the “vault”, is a quintessential element of Iranian architecture. “Imagine a square room, which is your prayer hall, for example, and you want to cover it with a dome—but the base of the dome is round,” explains Amanat. “So you have to solve the space between this circle and the right-angle corner of that room. Iranians have tried in very clever and beautiful ways to bring a straight line to a curve.”

Amanat explored this “vault” again in a recent sculpture, created specially for the exhibition “where/between” at Vancouver’s Equinox Gallery last year. The work, entitled Vault, is a steel lattice that rises high into the air, straight at its base but bending and warping gradually at its apex. Curated by Pantea Haghighi, “where/between” highlighted works by Iranian artists living and working internationally, and also included several of Amanat’s architectural drawings. This fall, the show will tour to the Southern Alberta Art Gallery in Lethbridge.

Amanat is in good company among artists. The architect came of age during a renaissance in Iran, a brief but significant period between World War II and the Iranian Revolution when writers, visual artists, musicians, and architects drew ideas from their own country’s antiquity. Rather than looking westward and copying aesthetics of modernism that were proliferating in a newly-globalizing world, the cultural scene of Tehran revived centuries-old traditions in innovative, present-day iterations. Just as Amanat brought aspects of ancient buildings into contemporary architecture, visual artists such as acclaimed sculptor Parviz Tanavoli, and those affiliated with the Saqqakhaneh Movement, newly invoked calligraphy and folk art motifs.

“When you sketch a building, it’s like a meditation on that building. You see every corner of it.”

“Iran has more than five thousand years of history, three thousand of it recorded to a degree,” says Amanat. Despite his calm demeanour, he can’t disguise his unfettered captivation by his motherland, and he lights up as he talks. “So you get fascinated by what happened in this land.”

Art continues to inspire Amanat. After all, as he points out, “the essence of architecture has a relationship to the human soul.” Amanat observes how navigating built spaces—how a room is lit, or proportioned to the human body, or entered and exited—is like music, with varying cadences, dynamics, and rhythms.

And wherever he travels, Amanat discovers new techniques and styles that inform his own practice; most recently, he spent time in Italy and Tibet. Yet, the one place he cannot visit—Iran—is never far from his thoughts. Amanat admits that being cut off from Iran’s cultural atmosphere, and the dialogues taking place, has been difficult for him. “Now, my days in Canada equal my days in Iran,” he notes with a solemn smile. “I lived 37 years in Iran, and now I have been 37 years in Canada.”

Fortuitously, Amanat is designing a house for prominent collectors of contemporary Iranian art. “It’s supposed to be a single-family home, but it’s ending up as an art gallery,” Amanat says with a laugh as he describes the West Vancouver property. This isn’t far from the truth, though. The art collection is so large that it cannot be displayed all at once; and thus, the house—like a museum—must be suited for constantly-rotating exhibitions. “This project is a pleasure to work on, because you constantly have art pieces in front of you, full of beauty and interest,” he says. “I really enjoy that.”

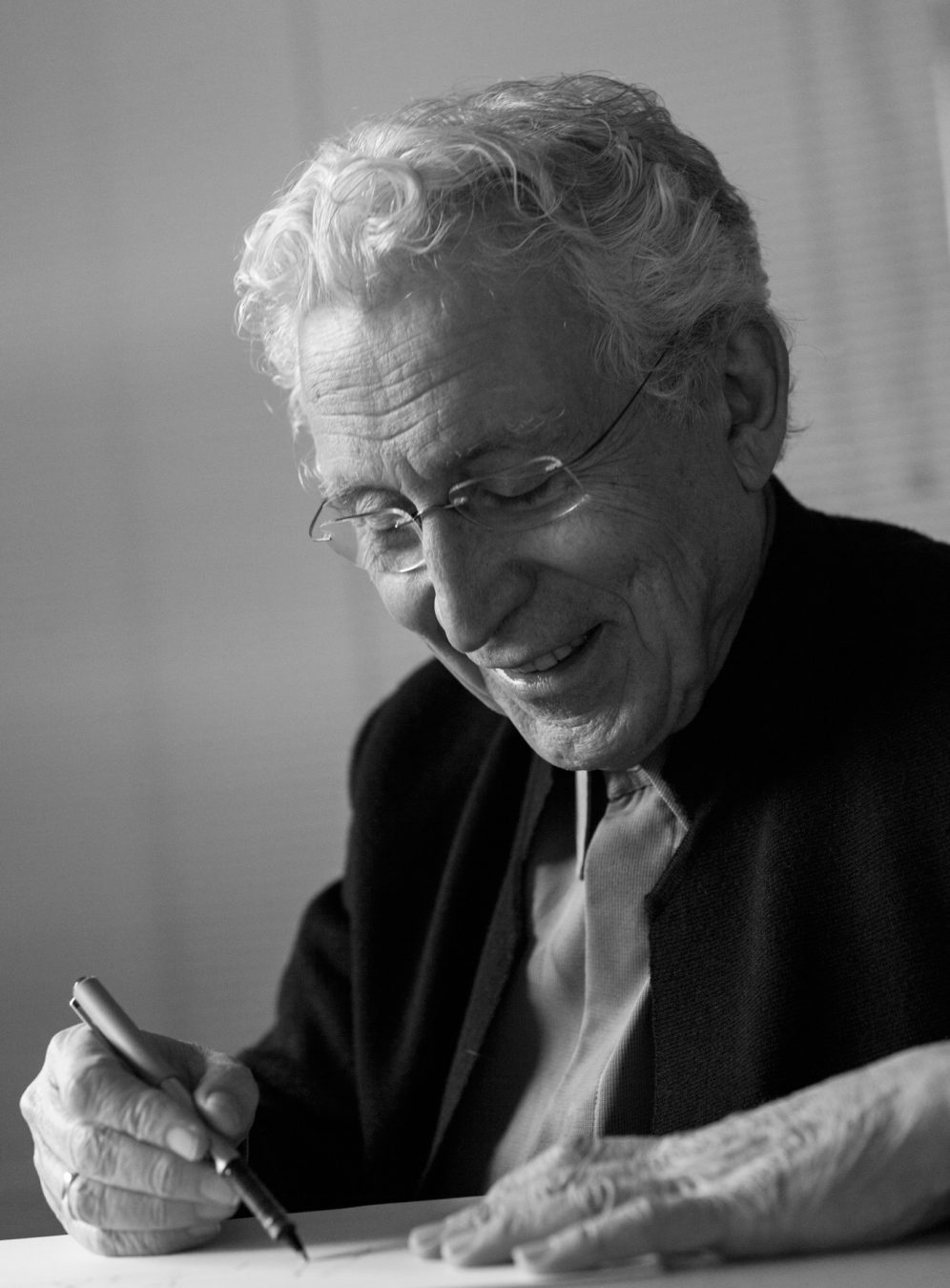

Despite his appreciation for diverse art forms, Amanat does not turn to any mediums other than paper and a writing utensil when starting a project. He is constantly drawing; somewhere in his sketches, he might discover a draft for an upcoming venture, or a solution to a present problem.

Amanat brings out a selection of his architectural sketches. They’re detailed but freehanded: there is great attention to form, to beauty, more so than to material or technical specifications. Their most arresting feature is the liberal use of coloured pencil, which shades the environs with rich blues, warm yellows, and dusky lavenders, sometimes reflected in the buildings’ windows. “I’m not very realistic,” Amanat concedes. “I’m idealistic, I should say.” Freed from logistical concerns, Amanat’s ideas flow onto the page unimpeded; from there, they find their way to standing fully realized. “You have to solve problems,” he declares. “I create a spirit and soul in a space so that it’s impressive and interesting. That’s what I try to do.”

Read more about architecture.