When Johann Roduit first visited Golden, B.C., in September 2020, he was struck by a cluster of dilapidated cabins clinging to a mountainside on the edge of town. The Swiss social entrepreneur, who had moved to Abbotsford in 2018, couldn’t miss the resemblance: the half-timbered houses with intricate bargeboards and wraparound balconies echoed the traditional chalets of his native Alps. Intrigued, he asked around and soon found himself at the Golden Museum, where executive director Brittany Newman told him the story of Edelweiss Village and the once-famous Swiss guides.

As improbable as it sounds, this collection of cabins marks one of the birthplaces of Canadian mountain culture. The story begins in the late 1800s, when the Canadian Pacific Railway began enticing wealthy alpinists to British Columbia with the promise of “50 Switzerlands in One.” Visitors flocked to the Rockies and Selkirks for the thrill of conquering untouched peaks. But the region’s dense forests and treacherous summits demanded expert guidance, risks that became tragically clear when climber Philip Stanley Abbot fell to his death on Mount Lefroy in 1896.

The CPR took notice and, in 1899, hired Eduard Feuz Sr. and Christian Haesler Sr., the first of dozens of Swiss guides who would go on to shape Canada’s alpine traditions by leading hundreds of first ascents, teaching safe mountaineering techniques, and participating in the films and photographs that sparked widespread interest in the mountains. Dressed in traditional climbing garb, the guides were photographed tackling soon-to-be-iconic peaks including Mount Assiniboine and Mount Victoria. By the 1920s, the mountainous region’s fame grew further as the CPR’s Swiss team began guiding for the film industry, eventually acting as stuntmen and supporting cast alongside stars including John Barrymore and Marilyn Monroe.

The former home of Swiss guide Rudolph Aemmer. Photo by Diane Selkirk.

Initially the guides worked seasonally, returning to Switzerland each winter. But by 1910, their popularity led the CPR to build them permanent family homes. The task of designing the village fell to Calgary architects George S. Rees and James L. Wilson, who, despite never having seen a Swiss chalet in person, created six whimsical three-storey houses. Opened in the summer of 1912, the houses were perched in full view of passing CPR trains, offering a pretty—if imperfect—nod to Swiss culture. In a comical twist, one façade bore the inscription Lebe Wohl (“farewell”) rather than Willkommen (“welcome”).

Captivated by the story of Edelweiss Village, Roduit was perplexed by its obscurity. “Alpinism, the art of mountain climbing, is listed by UNESCO as a form of Intangible Cultural Heritage,” he explains. His surprise deepened when the village went on the market. The National Trust for Canada listed it among the country’s top 10 endangered places, citing its vulnerable location in a rural area without heritage bylaws. “I couldn’t believe it wasn’t protected,” Roduit says. “Why would a country let cultural heritage be for sale?”

Determined to act, Roduit reached out to Ilona Spaar, a Swiss Canadian historian. Together, they co-founded the Swiss Edelweiss Village Foundation, an effort that quickly grew into a fundraising campaign to preserve the settlement. Although donations streamed in, it became clear the foundation couldn’t match the property’s $2.3-million price tag. Instead, they directed funds toward the digital preservation of Edelweiss through the University of Calgary’s Digital Heritage Archive, using a modelling tool often reserved for documenting at-risk architectural sites unlikely to be physically saved.

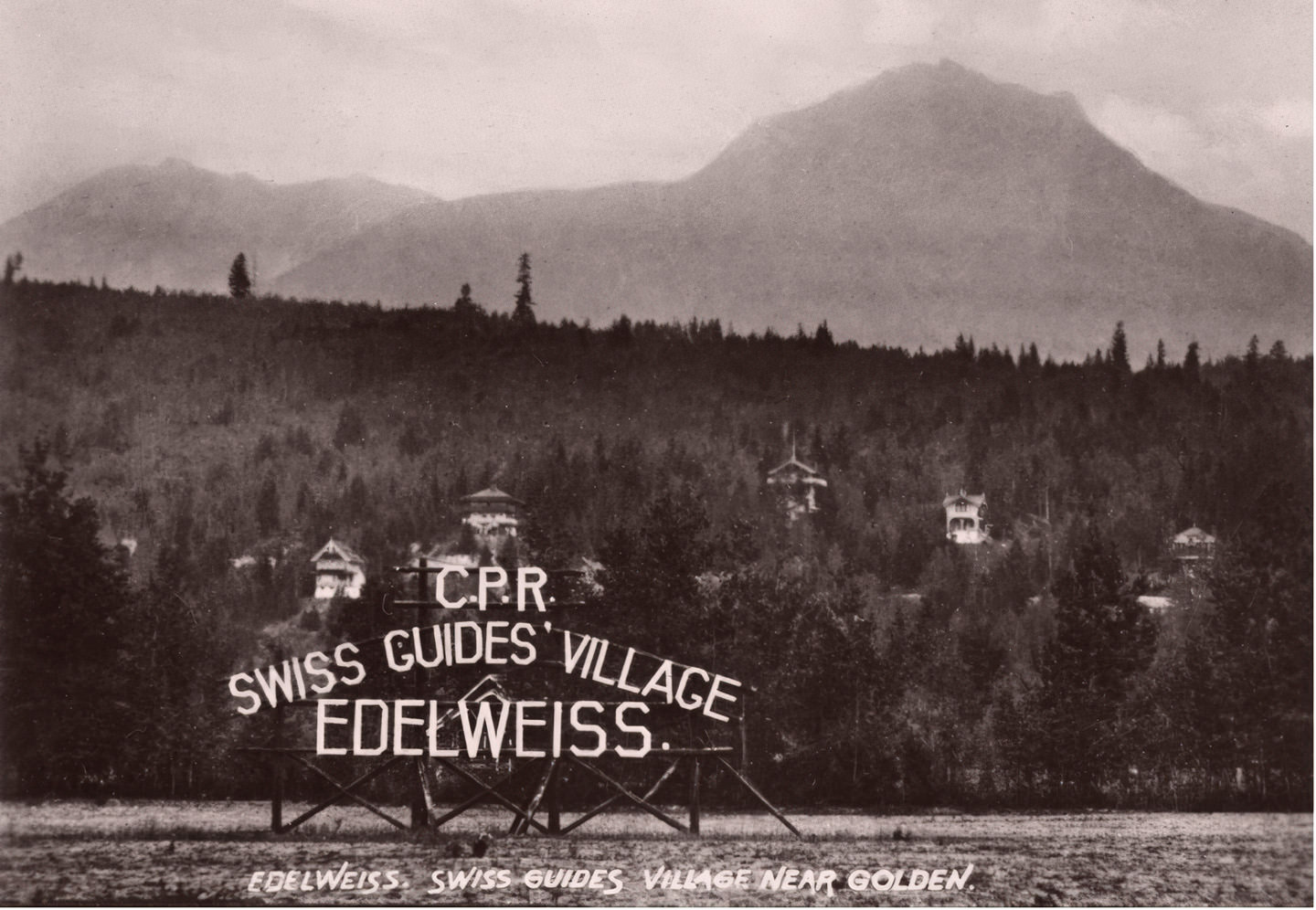

View from the railway track of Golden’s Edelweiss Village (NA66-1183x). Courtesy of the Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies.

Spaar spent hours at Edelweiss while laser scanners recorded each home’s every detail. The village, owned by the Feuz family since Eduard’s son Walter bought the 50-acre property from the CPR in 1959, bore the wear of its 110-year history yet still exuded a warm sense of history. “The Feuz family saved everything—photos, hats, ropes, even a climbing axe,” Roduit says, noting that Spaar salvaged many of the artifacts.

At the same time, inquiries began rolling in, including some from developers whose visions left little room for preserving the village. Yet momentum had begun to shift. Interested buyers were increasingly consulting the foundation for guidance. “Even the Feuz family was working with us to find the best fit,” he says.

Swiss guides with their families (V200-PA44-497). Courtesy of the Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies.

Set in the Rocky Mountain Trench, a 1,500-kilometre fault line stretching from B.C.’s Yukon border to Montana, the small town of Golden lies within the traditional homeland of the Ktunaxa Nation. Surrounded by some of Canada’s most mountainous national parks—Yoho, Glacier, Banff, Jasper, Kootenay, and Mount Revelstoke—it’s become an adventurer’s playground. The same peaks that first attracted early alpinists now host ski towns that draw multinational hotel chains eager for large, scenic plots of land unencumbered by even recent history.

Roduit and the Swiss Foundation feared one of these large players would ultimately claim the property and erase Edelweiss’s story. In July 2023, however, the Feuz family took a different path, selling the property to Montayne Capital Corp., a newly formed company created by a group of friends. “Our interest in the property was inspired by the history,” says Davin MacIntosh, a Canmore environmental lawyer and one of Montayne’s four co-founders, all residents of Alberta’s Bow Valley.

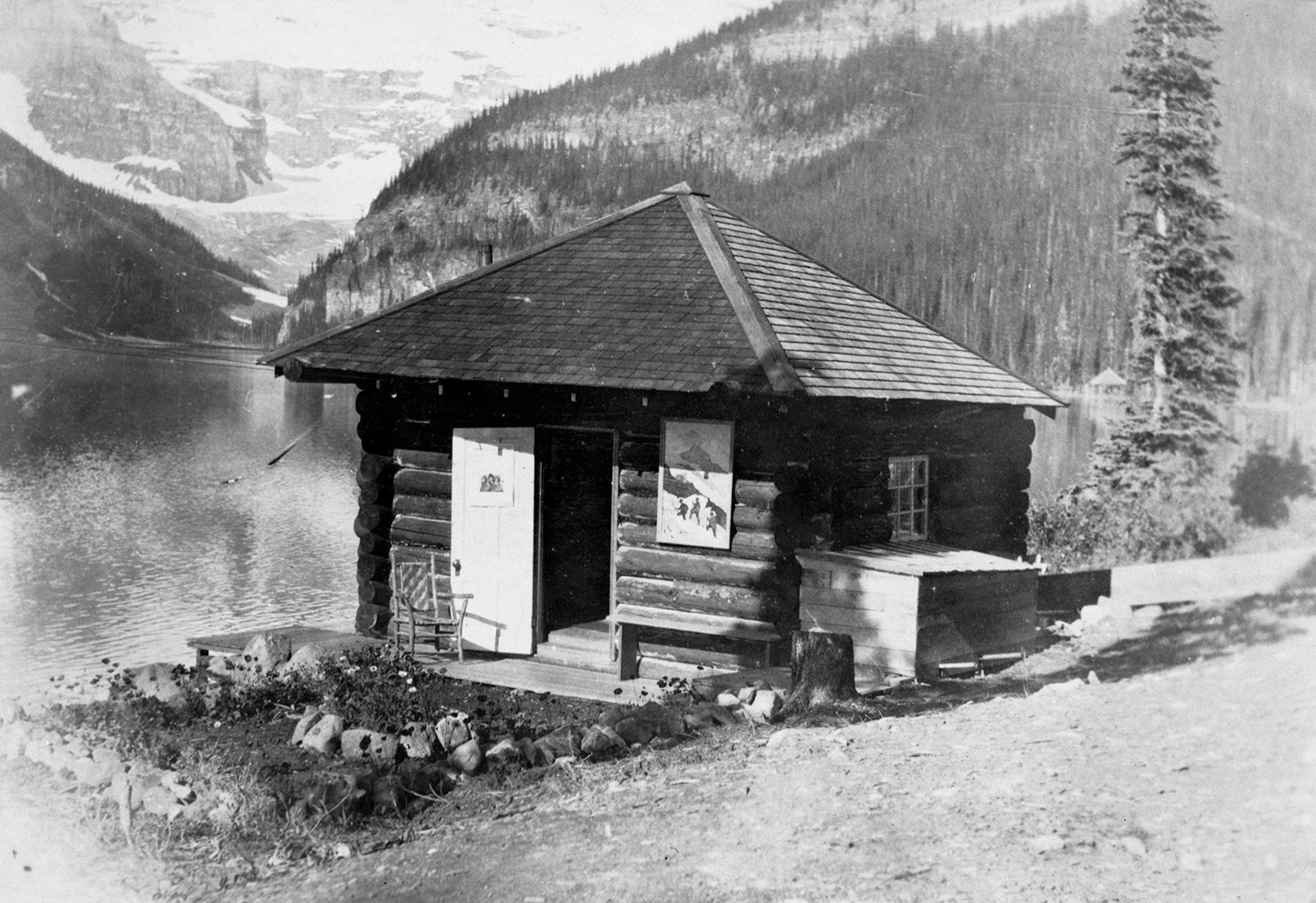

Courtesy of the Whyte Museum of the Canadian Rockies.

Initially, MacIntosh admits, the idea of working with the foundation slowed the purchase process down as Montayne did their due diligence. “They had a strong mandate but no legal powers,” he explains. However, he quickly realized their goals aligned. “Their primary objective was to save the buildings and preserve the story. And ours was to create a special property where guests could become part of the region’s history.” The foundation even offered a template, introducing the Montayne team to Vacances au cœur du Patrimoine, a Swiss program that restores abandoned historical buildings for tourist rentals.

With this model in mind, Montayne got to work. “We definitely had to use our imagination,” MacIntosh recalls of the long-empty buildings. The houses had crumbling foundations, broken windows, leaking roofs, damaged siding—and animals had come in. Despite the challenges, he says the village had its strengths. “We saw six cabins that were pretty ideally sized for short-term rentals and a beautiful site.”

Ernest Feuz chalet. Photo by Diane Selkirk.

Over the next 12 months, Montayne poured $3 million into restoring, renovating, and enhancing the chalets and surrounding landscape. The work wasn’t without setbacks—they had to take the buildings back to the studs to accommodate insulation and modern wiring—but as the structural work concluded, the rebuild brought opportunities for creativity. Drawing on artifacts provided by the foundation for inspiration, the team integrated historical photos, vintage climbing axes, skis, and snowshoes into the cozy interiors, while a cheeky photo of the old Abbot Pass Hut outhouse found pride of place in the new spa-style bathrooms.

The exteriors presented their own challenges. The design team tried to replicate the traditional colours, but they were hard to determine, even after scraping through the layers. Drawing on research into historical Swiss architecture and colour schemes, they discovered architectural parallels in the Swiss town of Appenzell. Believing photos from places like the old town may have inspired the original builders, they chose vibrant new colours from Appenzell’s historic palette, reviving the venerable chalets in a way that honoured their Swiss heritage.

The initial restoration of the chalets, completed for a fall 2024 opening, marked the end of Phase 1 for the renamed Edelweiss Village + Resort. Over the winter, barrel saunas and an upgraded trail network were added, with plans to include a destination spa and woodsy cabins in the coming years. Next on the agenda is replacing the property’s 1970s house with a Swiss Guides Great Hall for hosting meetings, weddings, and events while displaying original artifacts.

Although Edelweiss might seem like a quirky remnant of the Swiss Canadian connections that shaped Canada’s mountaineering culture, MacIntosh is excited about guests discovering its deeper significance. “Edelweiss already means so much to so many,” he says. “We wanted to celebrate the history and make something special so even more people can learn about its legacy.” Roduit adds, “Many people come to B.C. for alpine activities, but few ever stop to ask where these sports came from or how they came to be part of our culture.”

Former home of mountain guides Edward and Walter Feuz. Photo courtesy of Jonas Gordon.

Read more from our Spring 2025 issue.