Seen from the air—or, much more easily, through the magic of Google Maps—the area north of East Hastings and east of Renfrew is wholly distinct from anywhere nearby. From a distance, an oval is clearest—Hastings Racecourse. Closer, and you’ll see two white circles, the Agrodome and the Pacific Coliseum. Closer still and details emerge; the rides and tents of Playland form pinwheel patterns and various geometrics that speckle the concrete. The mini golf course. The rollercoaster.

There is rich history and enduring tradition here. Every August for the last 100 years, the PNE has opened its gates, ushering in hundreds of thousands of guests from across Vancouver, the Lower Mainland, the rest of British Columbia and beyond. The amusement park sounds from Playland, which is open between April and September, are amplified with the clacking of roller coasters and the screams of thrill-seekers. It is a Vancouver institution, the largest ticketed event in the province, and a summer tradition for many.

It is a tradition that, despite having seen major changes over the last 10 decades, also stays true to its origins. “The current fair has always had the same components,” says Debie Leyshon, the director of corporate services for the PNE, who also serves as the fair’s de facto historian and archivist. “If you look at the first fair, it had the rides, the agriculture—the same components, but has adapted to whatever the time period it is. That part has remained constant.”

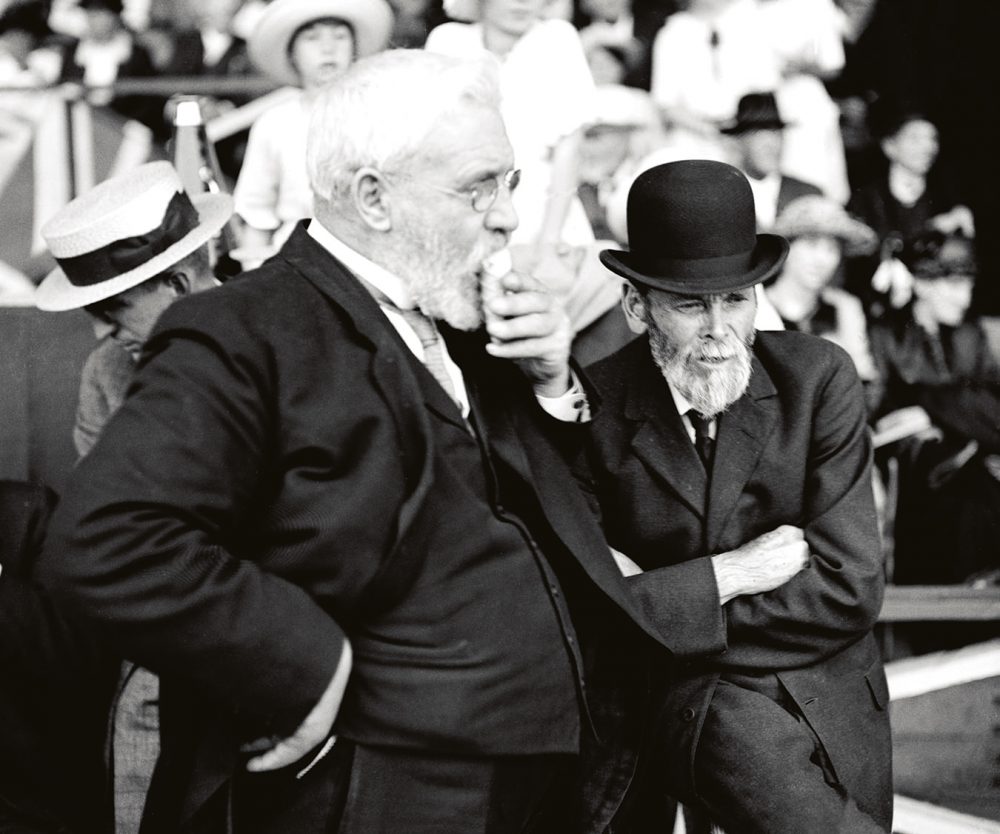

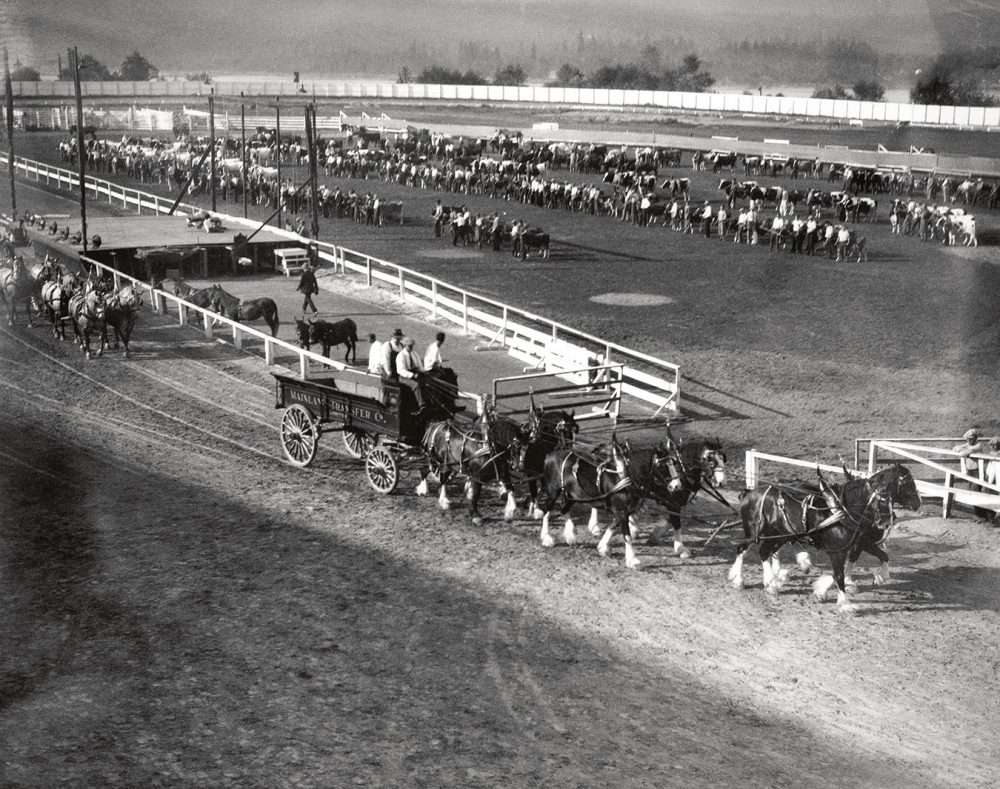

In 1907, the City of Vancouver, having been incorporated in 1886, turned 21. It was no doubt a fitting year for a group of Vancouver businessmen to meet and develop a new amusement for the city: a fair. They formed the Vancouver Exhibition Association, and three years later, on August 15, 1910, Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier opened the fair, then known as the Industrial Exhibition. At the time it was the largest event of its kind in Canada, and second only to the New York State Fair in North America.

Its location in the northeastern corner of the city served to promote development and transportation in what was, until then, the city’s hinterland. “Transportation was different back then,” says Leyshon. “The fair evolved with transport—extending out from downtown to the burbs. You got here by train, by tram, by boat. When it was first built, you were coming out to the boonies. If you lived downtown, it was a whole day’s adventure.”

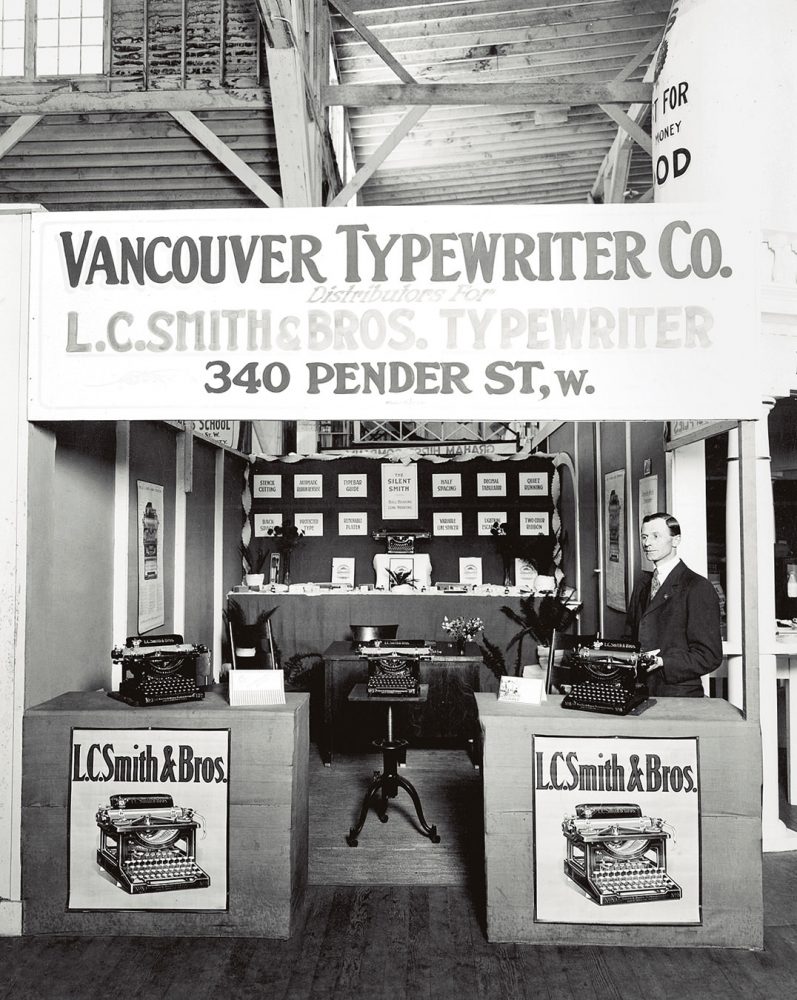

A story appearing in the Vancouver Daily News-Advertiser on August 16, 1910, describes a walk through the fair, and highlights various companies of the day having booths in the showcase section of the fair: “The first booth … is occupied by the Electric Water Heater company, where demonstrations of the efficiency of this system are given daily. The next booth is that which houses the display of the Singer Sewing Machine company while the Vancouver Garment company, with an exhibit of Vancouver-made garments and clothes comes next. The next three stalls are given over to the Woodward stores, with a general display of their wares.”

“The first fair, a curious amalgam of vaudeville, agriculture, industry and hucksterism … says something also about the character of Vancouver society at the beginning of the century’s second decade.”

“At the beginning, it was really a showcase for industry,” says Leyshon. “It’s like today’s tradeshows. That’s what it was at the time, along with the amusement park component. But along with showcasing the latest things and the industry, it had the novelty, the entertainment of the day.”

That entertainment aspect was, back then, known as Skid Road, and featured midway games, rides, and all manner of live entertainment: “petrified women, sacrificial crocodiles from the sacred river Ganges … to say nothing of the numerous Salome dancers, Spanish Carmens, Dutch comedians and chorus girls,” according to the Daily News-Advertiser. “Everything new and novel in the amusement line, every means that human mind can devise to gather in the spare nickel, dime or quarter of the amusement seeker, is now in operation.”

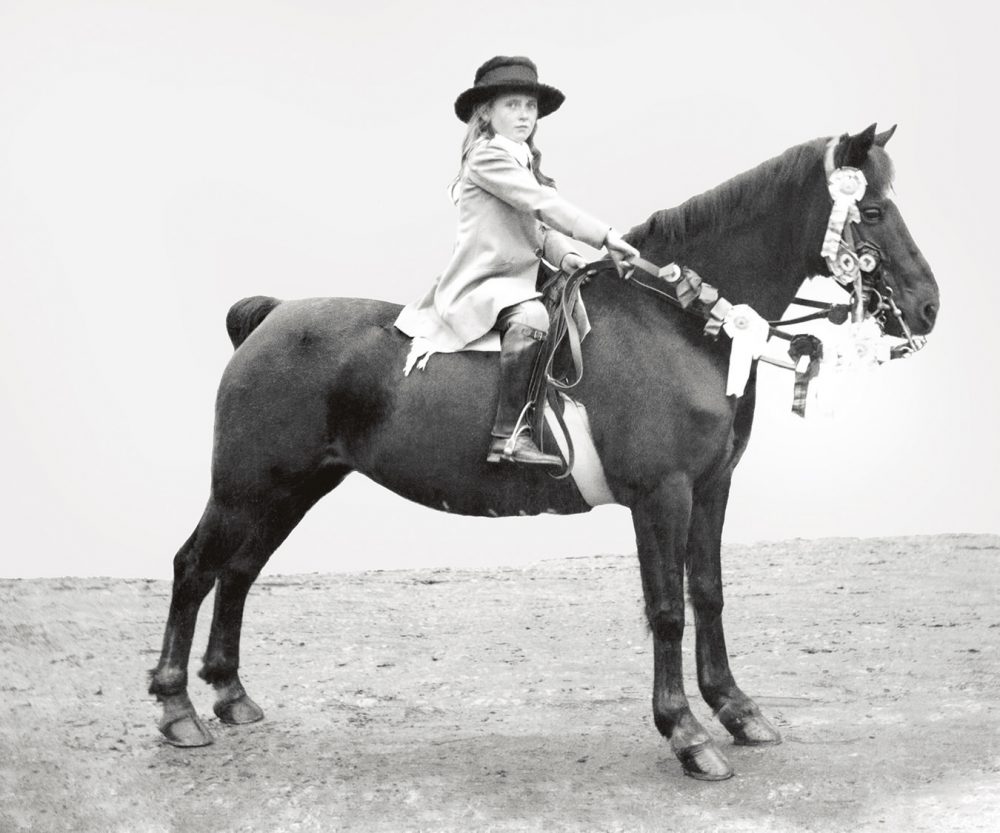

These entertainments were purportedly secondary to the main thesis of the fair, which was agriculture. However, the industrial and entertainment components immediately overshadowed the agriculture. Still, it was successful, and indeed indicative of the city as a whole in that particular era. In their extensive historical account Vancouver’s Fair: An Administrative & Political History of the Pacific National Exhibition, David Breen and Kenneth Coates write, “The first fair, a curious amalgam of vaudeville, agriculture, industry and hucksterism, provides evidence not only of the association’s attempts to stage a successful exhibition, but it says something also about the character of Vancouver society at the beginning of the century’s second decade. The city was at a transition stage in its development, exhibiting the characteristics of a comparatively new frontier settlement while at the same time there was evidence of a more settled community with metropolitan pretentions. Gambling, horse racing, and the carnival atmosphere of the Hastings Park show were clearly directed towards the baser instincts of the frontier community, a city that was still rough around the edges. At the same time, however, the fair also contained elements attractive to the more staid and conservative members of society.”

Since those early days, every year has seen its own particular innovation, or change, or challenge. The fair remained open during the First World War, a controversial decision exacerbated by the fact that nearby fairs in New Westminster and Victoria were closed. And despite the Great Depression, the fair did a steady business in the 1930s, with attendance numbers rising from 200,000 in the 1920s to 377,000 in 1936. “People need something during the hard times,” says Leyshon. “They need that release. Even though they didn’t have much money—probably brought their lunch, didn’t buy stuff—they came out to the fair and took advantage of the free entertainment. Sort of like an escape.” The theme of the 1932 exhibition was, optimistically, “Back to Prosperity”.

All this to say that there are traditions—lots of them, many that you probably wouldn’t even realize—that have originated at the PNE. And that, indeed, is one of the reasons people keep coming back.

The early years of the Second World War saw increased military presence during the fair. Following the attack on Pearl Harbour, the Vancouver Exhibition was cancelled from 1942 to 1946 due to the war, although there was still a lot of activity at the fairgrounds. In 1942, more than 8,000 Japanese-Canadians passed through the processing centre at Hastings Park on the way to internment camps in the B.C. Interior; the following years saw the grounds used for military drill practice and storage. The fair would reopen in 1947 with a new name: the Pacific National Exhibition.

“After the Second World War, the name changed, the focus changed a bit—everything was booming again,” says Leyshon. “People were building houses, buying new appliances—and where would you see these new products? Here.” As a result, the PNE became the place to experience all that was cutting edge. “We’ve had lots of firsts. The first lawnmower in B.C. was featured here. They had a display—it was a guy going up and down Renfrew Street mowing the lawn.”

Similarly, many of the city’s events that remain to this day originated at the PNE. The Vancouver International Boat Show, the B.C. Home and Garden Show, and the Vancouver International Auto Show all had their start at the fair. Also of significance was the Better Babies Contest. Started in 1913, the program allowed parents to have their children examined by a team of doctors for a fee of 50¢. Those with health issues were advised accordingly, and healthy babies received an award certificate. The data compiled from the examinations raised the awareness of children’s health, and even led to better health facilities for children at Vancouver General Hospital. “The research they gathered from the contest was important in formulating preventive medicine and health care for kids,” says Leyson. “It wasn’t something they necessarily had specialized in at that time.”

All this to say that there are traditions—lots of them, many that you probably wouldn’t even realize—that have originated at the PNE. And that, indeed, is one of the reasons people keep coming back. “We haven’t had official seniors’ days for a number of years now,” says Leyshon. “Yet any Tuesday or Wednesday during the fair, doesn’t matter rain or shine, there’ll be people out here who used to come out on seniors’ days. Why have they come today? Because they did years ago.”

The theme for this year is “100 Years of Fun”—which it has been, unquestionably. But it has also been a lot more. Like the markings made on a door jamb that measure one’s growth, the PNE shows how much Vancouver has changed. Where it’s been. And in that way, it has become more than tradition, but something inexorably linked with the city as they have both grown through the years.