We’ve all dreamt it before: being someone else, being somewhere else, a change in circumstance that reveals something of who and where we are now.

Director Wim Wenders provides one of the great examples of the longing made manifest with Wings of Desire (1987). In the still then-divided city of Berlin, a cast of angels shadow the citizens of the city, listening to their desperate and lonely thoughts, bearing witness to small beauties, testifying to existence. When through the eyes of the angels the film is black and white, transforming to colour when the perspective shifts to the mortal, human point of view. This formal gesture is mirrored in the emotional landscape of the central angel character, Damiel, as a longing for the richness of the world: to taste the bitterness of coffee, to inhale the smoke of cigarettes, to be pressed upon by another. Having become spellbound by a trapeze artist, Damiel considers the weight of exchanging his immortal perspective for all the trappings of being human. Compelled by the possibility of knowing the woman of the circus, and further convinced by a fellow angel-made-flesh (played brilliantly by Peter Falk), Damiel falls to earth, exchanging immortality for inevitable death, observation for experience. And so another journey begins as Damiel writes himself anew, echoing a question asked at the film’s beginning: “How can it be that this ‘me’ that I am wasn’t ‘me’ before I existed, and that someday this ‘me’ that I am will no longer be ‘me’?” Identity begins and ends, and we become other in ways that cannot be predicted.

Sometimes, factors other than desire are at play and change is forced upon us, challenging our understandings of identity. In Hirokazu Koreeda’s 2013 film, Like Father, Like Son, a devastating piece of information threatens to alter the composition of two families. Learning their sons were switched at birth, the film focuses on the disjunction between nature and nurture, between biology and love. In our contemporary world, where families are composed in myriad ways, blood ties are a rather old idea, but the allure of family resemblance cannot be undone. Is being a father a brute fact of shared genes? Or it is a set of actions manifest through time? Heartbroken, the two families contemplate their options, none of them clear, all of them awful, of trading the six-year-old boys back, of keeping their families in tact as is, or of something else between these poles. In the various attempts to address the claims of biology and somehow set things right, one father in particular—overworked and somewhat distant—must grapple with an internal conflict that challenges not only his role as a father, but his own role as a son, re-writing his understanding of himself alongside the re-writing of his understanding of what a family is.

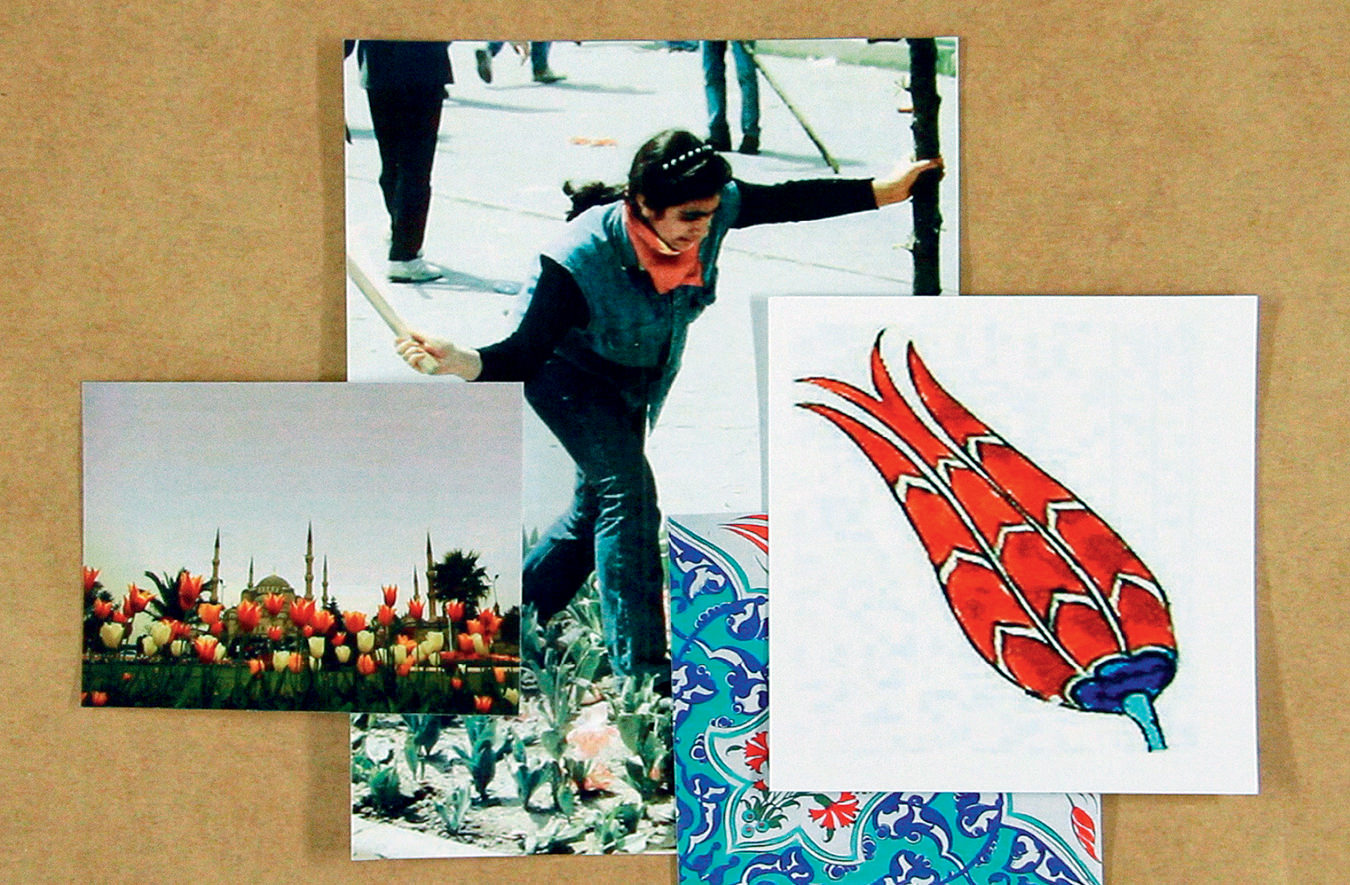

Other times, the shift in embodiment we imagine stays put in our minds, which is not to say that it is impotent, but that it reveals something of who and where we are, irrevocably. In Aykan Safoğlu’s short film, Off-White Tulips (2013), he traces his identity along the lines of another. Equal parts essay and autobiography, Safoğlu constructs an understanding of his self—Turkish, gay, an artist—through an exploration of James Baldwin, the influential American writer and social critic who spent time in Turkey in the 1960s. Formally, the film might be better described as a collage: it is composed mostly of a long series of still images laid on a flat surface, alternating between family photographs from Safoğlu’s personal archive, postcards, newspaper clippings and the torn-out pages of James Baldwin’s Turkish Decade: Erotics of Exile, a book of photographs by Magdalena Zaborowska documenting Baldwin’s life there. As images are placed alongside one another, meaning seeps and influence accrues. Across distance and time, Baldwin’s experiences of exile and embrace inform Safoğlu’s coming of age, creating some third thing (as is the case when any two things merge), here being biomythography, the term Safoğlu uses to describe an invented biography. When Safoğlu confesses that “Your [Baldwin’s] writings help to see clearly what my own life story is and how to make meaning out of it”, he reveals that we need other people for this making sense of ourselves. We are beings composed through relation, which is both desperate and desirous.

Canadian poet and essayist Anne Carson has said that “we think by projecting sameness upon difference, by drawing things together in a relation or idea while at the same time maintaining the distinctions between them … In any act of thinking, the mind must reach across this space between known and unknown, linking one to the other but also keeping visible their difference”. In the dream of being someone new, someplace different, we bridge the space between “you” and “I,” we become other and thus entwined.

ABOVE: Film still from Aykan Safoğlu’s Off-White Tulips (2013). Image courtesy of Aykan Safoğlu.