If you were travelling in the Dorset region of England’s seashores in 1826, you probably would have visited Anning’s Fossil Depot. You would have heard of Mary Anning, the impressive selection of fossils she unearthed, and her vast anatomical knowledge, despite her lack of formal education. Alongside geologists, scientists, and collectors hailing from Europe and even America, you would have paid a few pounds to own a piece of early history. A pioneer in the emerging field of paleontology, Anning was credited with finding the first complete specimen of the Ichthyosaur and the Plesiosaur; her work was fundamental to science’s understanding of prehistory.

In the two centuries since Anning’s work, the fascination with fossils, bones, and minerals continues, though prices are a little heftier than the £23 ($44) paid to her for the Ichthyosaur. Today, some specimens sell for seven figures; the international trade in fossils, minerals, and other natural history “curiosities” is a multi-million dollar industry. Once limited to dealers trading in musty rock and mineral shops, the advent of online transactions and international auction houses holding well-billed sales has helped to develop the market. Every year the Arizona Mineral & Fossil Show features minerals, dinosaur fossils, gemstones, nature-related specimens, and lapidary material attracting exhibitors and collectors from across the globe. Available specimens range from Triceratops horns, meteorites, and coprolites (fossilized faecal matter) to opals and diamonds.

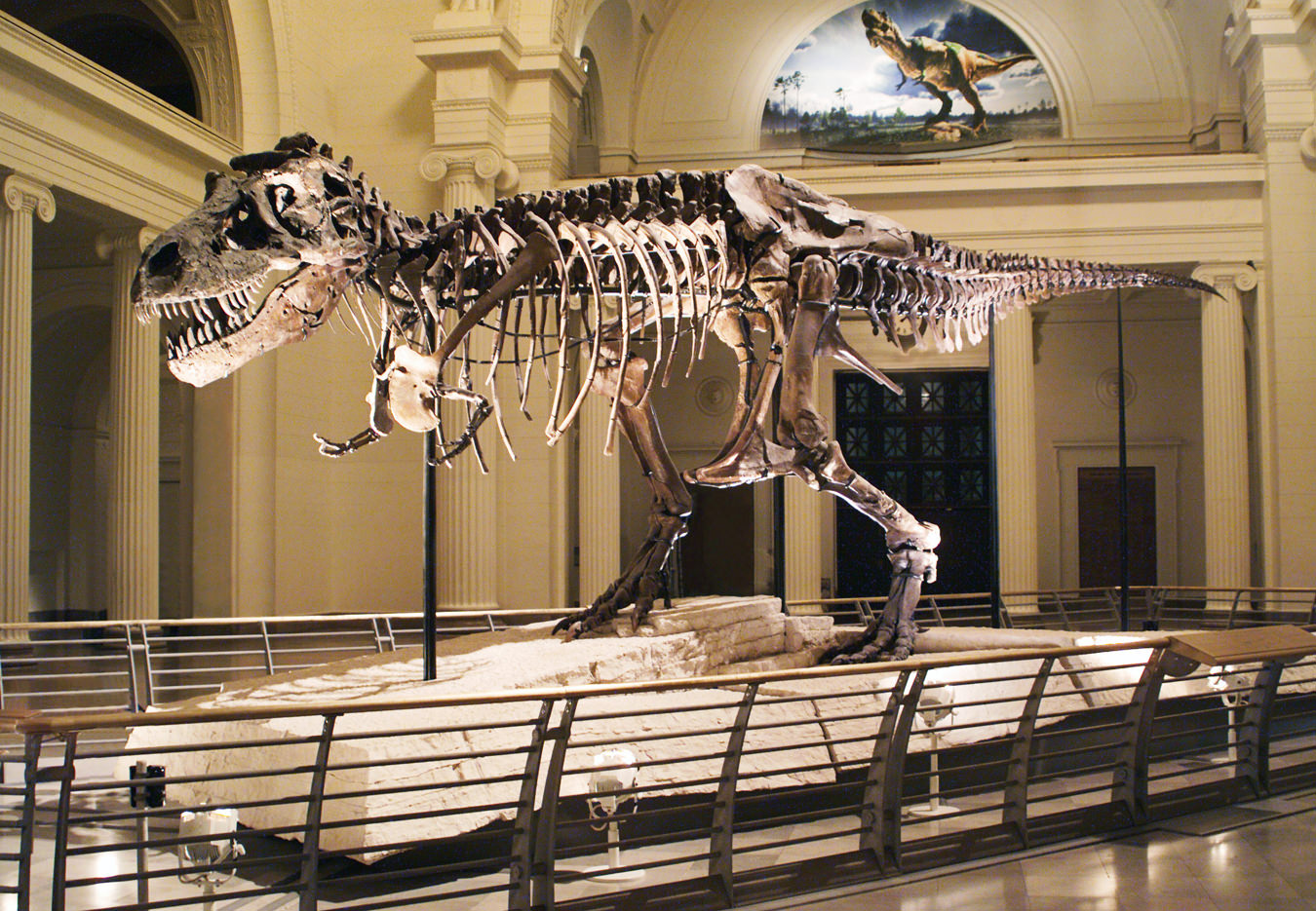

A defining year in the market was 1997, when Sotheby’s sold “Sue”—the largest and most complete specimen of a Tyrannosaurus rex—to the Field Museum in Chicago for $8.36 million USD after a heated six-and-a-half-minute bidding war. The price tag set a record for the largest amount ever paid for a fossil and was the catalyst for significant changes in the market, paleontology, and its governing federal policies. As prices for specimens rose, private land owners preferred to work with commercial bone hunters with the hopes of glittering financial returns; federal lands were pilfered by fossil poachers willing to risk the penalties for big payoffs. And as a nascent black market expanded, items that were illegally excavated, exported, and sold resulted in countries around the world introducing new civil and criminal repercussions for poaching.

The Gobi Desert in Mongolia has long been a prime location for illegal excavation due to its broad expanse of fossil-rich lands and limited governmental enforcement. It’s also a country that prohibits the private ownership and commercialization of its natural history. A well-known case features the illicit export of a Tarbosaurus bataar (a T. rex cousin) from Mongolia by dealer Eric Prokopi. In 2012 the specimen was offered at auction in the U.S., but after the hammer went down at around $1 million, the skeleton was seized, as the Mongolian government had sued for its return. Consequent investigations of Prokopi and other dealers resulted in the return of this and other specimens, sentences for felonious smuggling, and a peek into the pool of the black market. Mongolia now has the Central Museum of Mongolian Dinosaurs to house and celebrate these repatriated relics.

Many paleontologists cite another concern with the commercialization of fossils: the potential loss to science and to the public’s greater understanding of earth’s geological and biological processes. Some do not support the trade in fossils at all, arguing that valuable scientific data—including potential new discoveries—are lost when specimens are improperly removed or excavated without contextual information, or disappear into private collections. As museums, universities, and similar institutions cannot always afford the hefty price tags that accompany unique finds, often the purchasers are private collectors with deep pockets who may or may not be willing to work together with scientists. Not only does science lose out on new scholarship and understanding, but we do, too.

Times have changed since Mary Anning shilled her specimens on the shores of Dorset. Excavation methodologies have evolved from the simple basket and pickaxe used in the earlier centuries, and prices have risen to a headline-worthy status typically only associated with artworks by blue-chip artists—but our passion for connecting with and collecting prehistory remains as strong as ever.