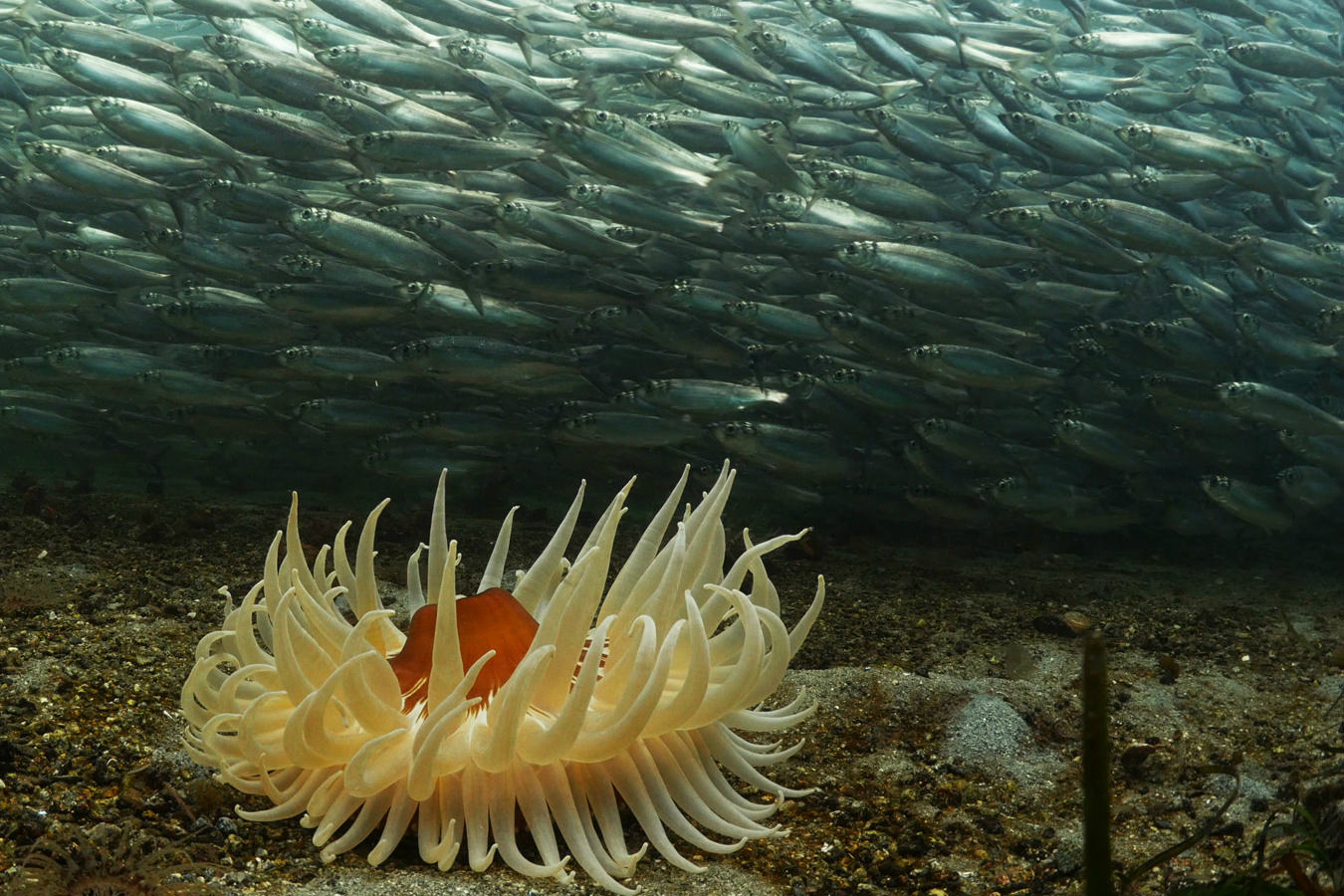

If you’re truly fortunate, maybe you’ve witnessed one of the miracles of West Coast nature. The Pacific herring spawn occurs annually in sheltered coastal B.C. waters sometime between February and April. While its precise timing is challenging to predict, a chance encounter will leave an indelible memory.

The herring spawn offers a compelling snapshot of the food chain in its purest form. Just prior to the phenomenon, wildlife of every kind imaginable gathers in anticipation, from bald eagles by the score to seals, otters, mink, bears, sea lions, seabirds—especially herring gulls by the thousands—and many, many more. To hear the cacophony and watch the feeding frenzy over an ocean (which turns an opaque shade of turquoise) is to be a bystander at nature’s most extraordinary and bountiful dinner party.

That appetite for Pacific herring (Clupea pallasii)—or, more specifically for its spawn—is shared by First Nations, whose people have harvested, stored, and traded the eggs for thousands of years. And the herring, once they do show up, are nothing if not predictable—and prolific. Sometimes it seems almost everything in sight is covered in millions of pale, washed up eggs, along every rock and sandy shore. Obligingly, the herring lay their eggs on broad-leafed kelp, which is easily collected and even rearranged for the convenience of cleverly corralled fish—although humans have also learned to harvest in other ways. A small hemlock with open branches will suffice. Even a single tree left in the water during the height of the spawn for just a few days may be hauled to shore absolutely covered in eggs, ready for easy picking and processing, smoking, and drying.

However, it is specifically spawn on kelp that sushi aficionados appreciate. No wonder Japan accounts for almost 100 per cent of the B.C. harvest—although it remains highly prized by First Nations, who still regard it as part of their cultural heritage and strive to protect their harvesting rights. The spawn on kelp harvest is also deemed ethical and highly sustainable: mature herring can live up to 12 years, returning annually to spawn in coastal waters, a crucial link in the coastal ecosystem and food chain. That’s not the case with the commercial herring roe fishery, where the fish are killed in the process of the eggs being harvested prior to spawning, which many suspect is placing the spawn on kelp harvest in jeopardy.

In the last few years, even allowing for a certain level of unpredictability, some areas of the coast are seeing smaller herring runs. The Central Coast commercial fishery was closed entirely from 2006 to 2014. Both Haida and, most recently, Heiltsuk First Nations have taken actions to shut down its reopening, in the face of what they perceive to be continuing “perilously low” stocks. Still more worrisome, in terms of the broader ecosystem, the herring, they suggest, is the proverbial canary in the coal mine.

As far as its flavour is concerned, to say that spawn is an acquired taste would be an understatement. It’s definitely ocean-salty but also on the bland side, not as intense as salmon eggs, and not even close to sturgeon. Ultimately, it’s the textural experience that sets herring spawn on kelp apart.

Images by Pacific Wild/Ian McAllister.