Toby Reid wants to say just this one word to you: plastics.

Bio-plastics, to be precise. The kind made from plants, or that are compostable, or both. The kind that don’t clog up landfills. Or pollute the ocean. Or require millions of gallons of petrochemicals to produce. Reid believes there’s a great future in them. And he wants you to think about it. “Nowadays, there is no part of the world that doesn’t have to deal with plastic pollution in some way, shape, or form,” Reid muses. “Even from space, you can see plastic debris. They had trouble looking for the Malaysia Airlines flight that crashed because there was plastic debris on the ocean. So yeah, it’s a big deal.”

Reid’s Gastown-based company Solegear Bioplastics has been working hard to change that. Since 2006, Reid and his team of chemical engineers have been testing and re-testing recipes for plastic that’s built not to last: instead of sticking around for 1,000 years or so, it breaks down into soil and water in an industrial compost facility in under 180 days. Rather than tossing it into the garbage, you would throw it into the compost along with your eggshells and broccoli stalks.

The hard work paid off in 2010, when the company found a formulation that had never been tried before. “The key was that it worked to performance specifications as well as economics,” Reid says. “You can have lots of really interesting science projects. But if it costs 10 times more than what people are doing today, it’s always just going to be a science project. You have to attach a commercialization goal—it has to work.”

Since 2006, Reid and his team of chemical engineers have been testing and re-testing recipes for plastic that’s built not to last.

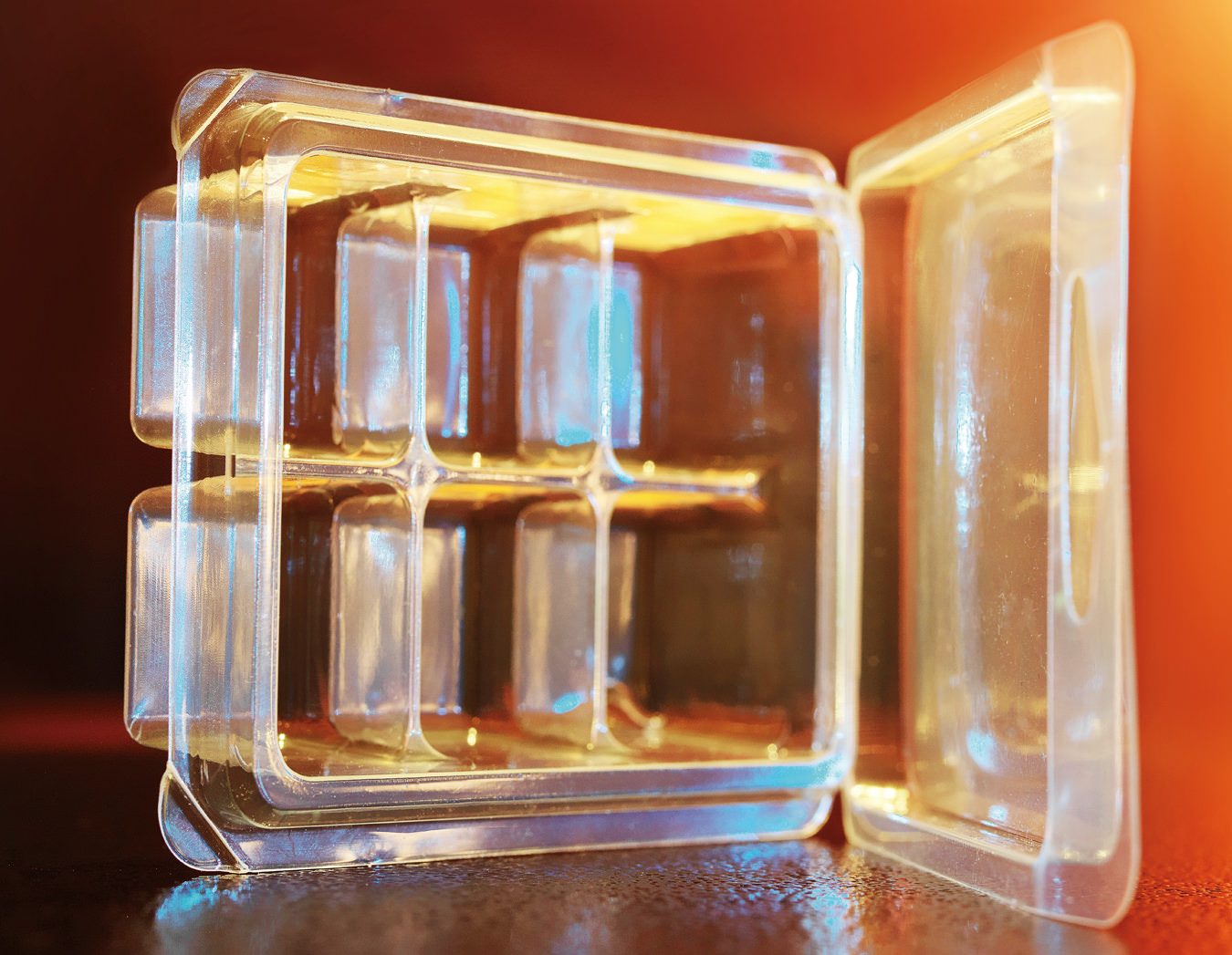

Fast forward to today, and Solegear is currently putting the finishing touches on a handful of highly visible deals that will see its plastic on store shelves across the continent. “Our focus is on consumer packaging,” Reid explains. “The hard stuff—not the flexible films or bags or anything like that.” He leans forward in his chair and reaches over to a tableful of proof-of-concept prototypes made from his company’s product. There’s a blue pill bottle—the kind your pharmacist hands out by the dozens. A small pile of plastic bricks made by an iconic toy company. A package for an iPhone case (Solegear is partnering with Best Buy). One of those stackable in/out boxes that help keep your files organized on your desk. “This [office supplies] is a product category that’s as stale as it gets in terms of innovation,” he points out. “It hasn’t really changed for 20 years. And now we’re going to be bringing new material into that category, and that’s going to get that category pretty excited, believe it or not.”

Right now, Solegear’s plastic is born of non-food-grade corn—the same stuff responsible for much of North America’s vegetable oil and high fructose corn syrup. But the company is working on expanding to other sources. “[In the future] it’s going to be made from the husks, the stalks, the wheat straw that’s been cut, grass clippings. Anything that’s cellulose,” Reid says. As he explains, that flexibility is a key benefit of Solegear’s product. “Depending on where you go in the world, you’ll have a much more localized feedstock to choose from—which, at the end of the day, is what this stuff is all about.”

As exciting as it all is, Reid insists he’s not in the silver bullet business. “There’s no one plastic that is the best plastic,” he admits. For now, it’s enough that Solegear will be a part of the solution and point consumers to a better future. “That’s the goal for Solegear: to be an agent of change, a lightning rod for transforming people’s views of what’s possible.” Just think about that.