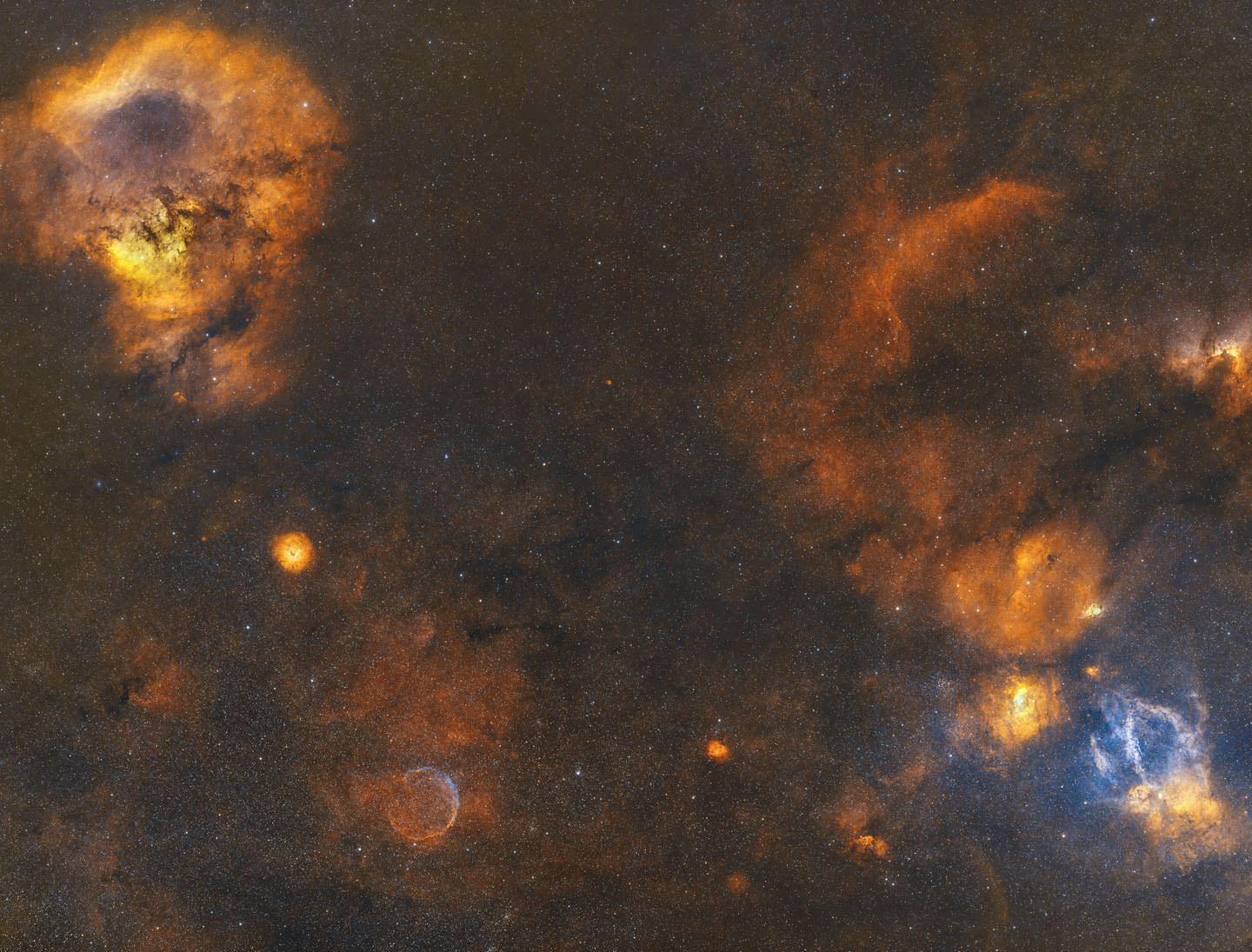

On clear nights, Rob Lyons climbs to the top of his Kitsilano townhouse and descends into the distant past. Lyons is an astrophotographer, and a serious one. He has several high-tech telescope-camera rigs mounted on his rooftop deck, including a large model housed inside a domed observatory that he uses to scan the universe. Inscribed beneath the dome’s rim is the phrase “The World Is Yours.” Using time-exposure star-tracking devices and special filters, he can take sharp, colourful images of swirling, gas-filled nebulae in the Milky Way that are 10,000 light-years away and glittering galaxies that are 30 million light-years from Earth.

“Some of the galaxies in the background of these images are more than 60 million light-years away; their light began the journey to make the picture when dinosaurs still roamed the Earth. Astrophotography is a type of time machine,” Lyons explains.

The Andromeda Galaxy. Photo by Rob Lyons.

Lyons took up astrophotography during the COVID pandemic. A professional photographer by trade, he had been employed in the health-care sector and was at the peak of his career when the work suddenly stopped. He was casting around, looking for options, when he saw a photo of the Orion nebula taken by a friend from his backyard. “It was not a great photo. Little more than a red smudge,” he admits, but it awakened a sense of possibility.

He began his own night sky investigations by purchasing a SkyWatcher Star Adventurer mount for about $500. A basic star tracker, it counters the Earth’s rotation and allows for longer exposures. He modified his DSLR camera by removing the filters that covered the sensor, making it more sensitive to near-infrared light, then ordered a narrowband filter from a company in Hong Kong. “It was the first of its kind and allowed me to photograph hydrogen and oxygen emission nebulae while cutting out the city’s light pollution,” he notes.

Using this setup, he photographed the Heart Nebula, a heart-shaped cloud of ionized gases located in the constellation Cassiopeia. Although the result was not great compared to images he had seen online and in magazines, “It was a masterpiece to me. It was a proof of concept and an invitation to keep going and exploring the night sky.

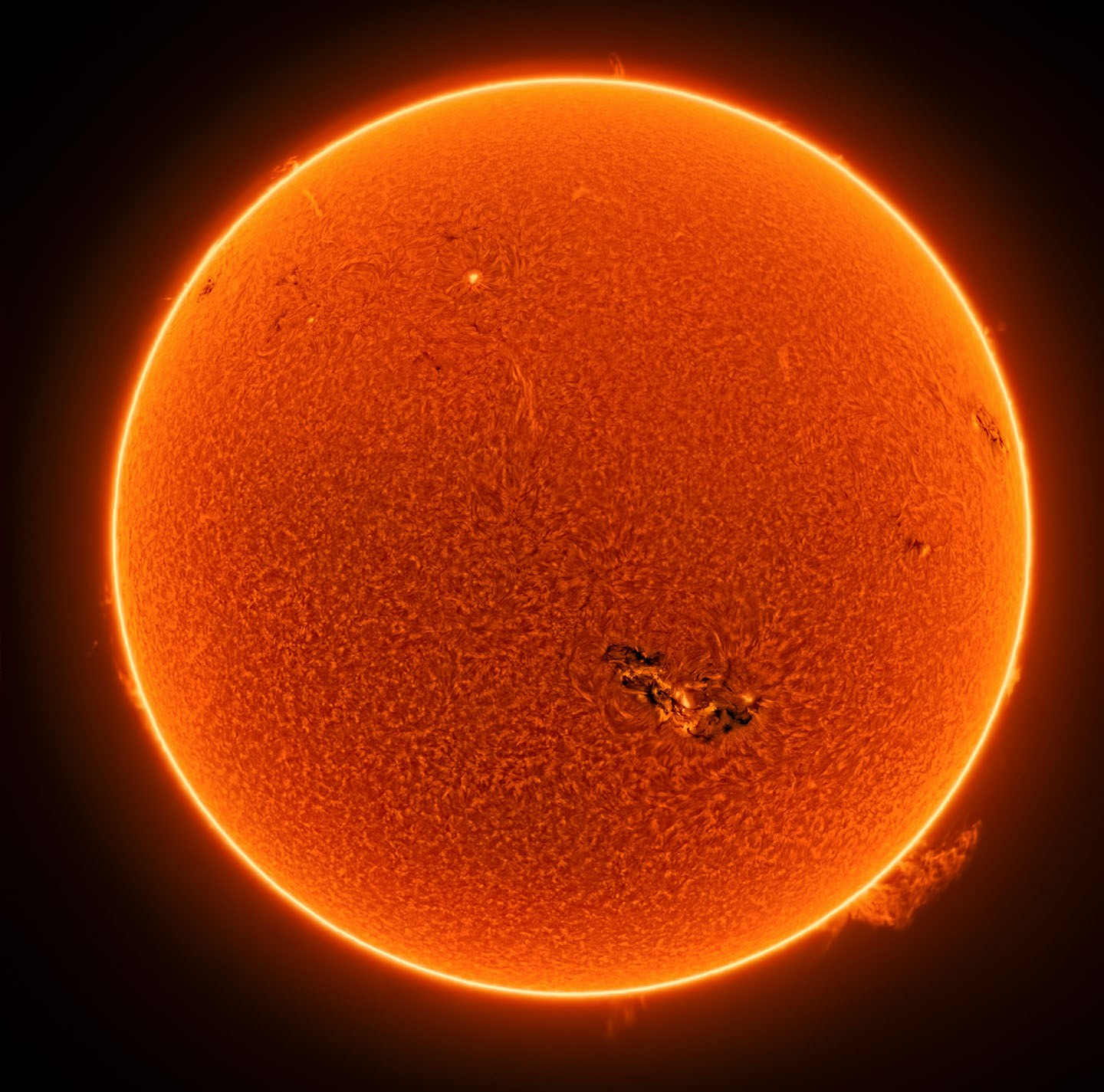

A plasma explosion on the sun taken May 8, 2024. Photo by Rob Lyons.

“I had spent 20 years as a professional photographer,” he says, noting that alongside his day job that included photographing and videoing surgical procedures, he pursued all types of photography—fashion, sports, street shots—on the side. Shooting the stars, he says, felt different: “Once I started doing astrophotography, I realized I had found my niche. I sold off most of my old equipment and went full-bore into it.”

He’s not the only one. While sales of traditional cameras have bottomed out, the market for astrophotography is exploding. The growth has been fuelled by the increased availability of user-friendly astrophotography equipment and vastly improved sensors, coupled with the rise of image-sharing platforms such as Instagram. Lyons knows of two other people in Vancouver with home observatories, and he estimates there are 15 to 20 people practising astrophotography in the city and likely a similar number in other large Canadian centres. Events held around the world each year see enthusiasts gather to photograph dark skies and share experiences and ideas, with 2025 expected to see a boom in “noctourism.”

“I call it piercing the veil, because you can only see a few bright constellations of stars from the city, but with the camera you can transcend that.”

The best local expression of this trend takes place at Simon Fraser University, which hosts star parties, weather permitting, every clear Friday evening in its Science Courtyard. These nocturnal gatherings attract about 250 people, who come to peer through the large telescope mounted in the Trottier Observatory and to view celestial objects through the telescopes of members of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, who show up at the event. Lyons, who is a former director of imaging for the society, often attends.

Astrophotography has become an obsession with him. Lyons is not simply capturing objects in the night sky. He is unravelling its secrets, constantly learning and pushing the boundaries of his knowledge. He now has his own website and operates his own YouTube channel, gives lectures, writes equipment reviews, and sells fine art prints of his photos.

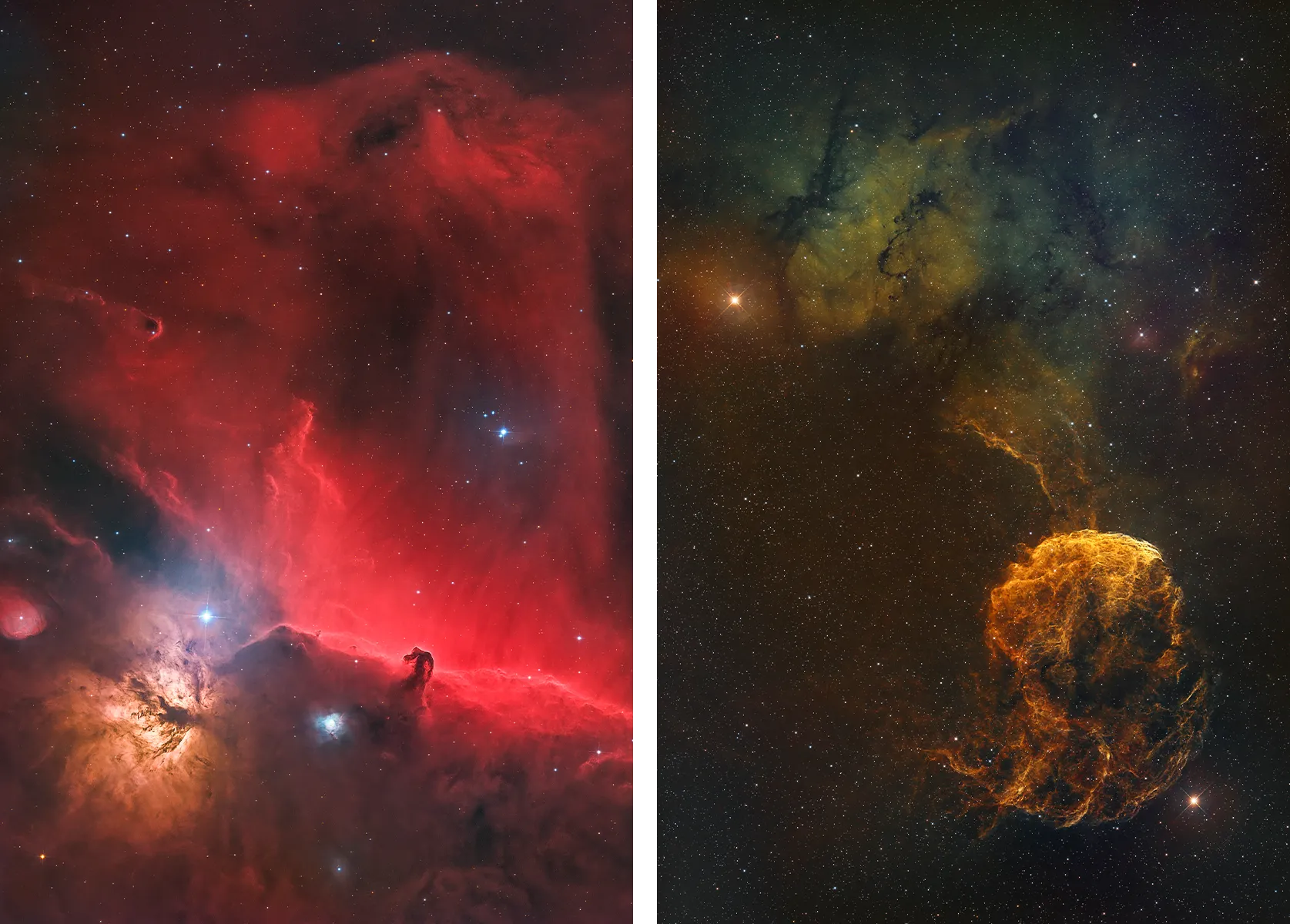

His photos of nebulae, the giant clouds of dust and gas where stars are born and die, are truly arresting. The writhing shapes in these images conjure up visions of rearing horses, crashing waves, jagged mountain peaks, threaded orbs, molten lava, and leering skulls. Everyone sees something different in them, but invariably they provoke a profound reaction.

Left: Horsehead and flame. Right: Jellyfish nebula. Photos by Rob Lyons.

“People talk about God and the glory,” Lyons proffers. “They touch a spiritual note. I call it piercing the veil, because you can only see a few bright constellations of stars from the city, but with the camera you can transcend that and ‘pierce the veil,’ revealing all the hidden mysteries of the universe that lie beyond. When you pierce the veil, it makes you think about why we’re here. Seeing these images makes us ponder our place in the universe.”

Last year, Astronomy magazine published a photo that Lyons took on May 8 of a plasma explosion on the sun. That eruption sent a vast cloud of charged particles hurtling toward Earth, sparking a geomagnetic storm that produced the most intense display of the northern lights in 35 years.

Lyons’s drive for perfection is remarkable. He will shoot 300 to 400 five-minute exposures over four or five nights and then stack the images together to improve the signal-to-noise ratio in order to make one photo. “I take an image of the night sky, and the computer software connected to my telescope and mount can analyze the image, plate-solve it—which identifies the exact coordinates of the area of space in the image—and then the computer can tell the mount to move or ‘slew’ to that exact position.”

He will then run the images through a complex processing routine to refine the image and perfect the colour.

Comet A3. Photo by Rob Lyons.

Hard-core shooters such as Lyons revel in the technical expertise needed to obtain excellent space photos, and they don’t hesitate to buy the latest and most sophisticated gear. Still, he insists, it’s not a hobby that requires a lot of money or know-how for beginners.

The technology and affordability are improving rapidly. For as little as $500, you can buy an all-in-one package that includes a telescope, camera, computer, tracking mount, and filters to block light pollution and allow solar photography. Smart scopes (the ZWO Seestar S50, for example) enable the user to take pictures of nebulae, galaxies, the sun, and the moon right from their smartphone or tablet with no prior astronomy or photography experience.

Meanwhile, Lyons is busy expanding his personal horizons. He is now pursuing an online bachelor of science in astronomical and planetary science at Arizona State University. “It’s all part of a five-year plan. I want to merge my photography, filmmaking, and astronomy together and produce my own content on social media. And I want it to be educational. It will evolve into space news, stories about cool things.”

His photographic output is doubly impressive considering the location of his observatory. Taking photos of the night sky in Vancouver is a perpetual challenge because of the frequent cloud cover and light pollution. To enjoy the full impact of the Milky Way and to recharge his batteries, he books a week’s stay in Tofino each year when there is no moon. “I call it my church. I go down to the beach, and there are so many stars I can’t even find the famous constellations that I’m used to seeing here. It’s a sea of stars. And it just hits you that you are in this majestic place. There is nothing we could build that is as incredible as being underneath a sky like that.

“When you see the Milky Way, it’s a grand design,” he adds. “And you start thinking about grander things. Why we’re here? How we got here? What’s out there?

“Our past is in space. We are made from exploding stars. And our future is probably also in space.”

Ironically, as his new vocation leads him to delve deeper into metaphysical questions and uncharted heavenly vistas, it has also reconnected Lyons with his past. “As a child, I loved science and space. For a long time, I wanted to be an astronaut. In a way, I’m living that childhood dream now.”

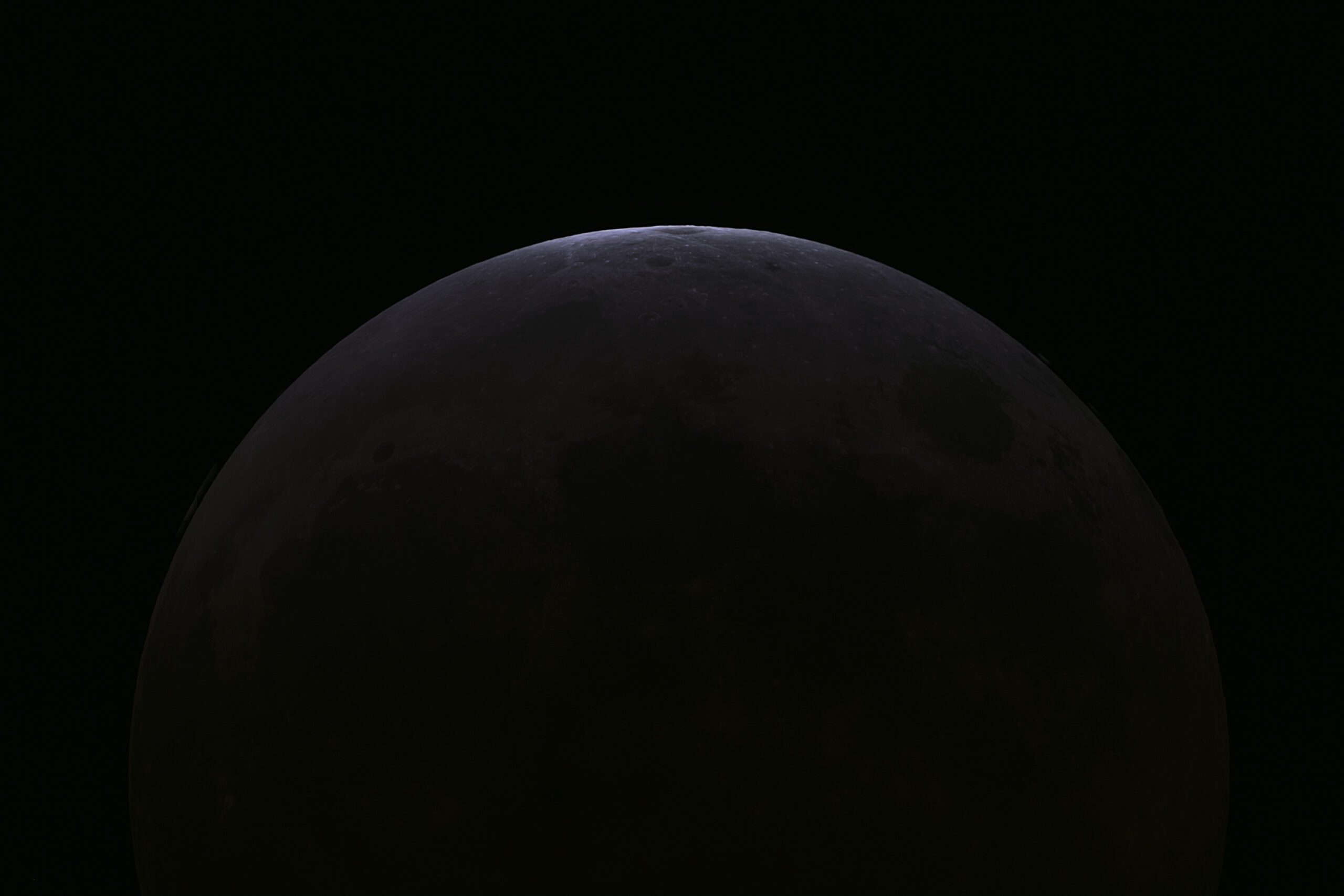

Approaching totality. Photo by Rob Lyons.

Read more from our Summer 2025 issue.