Many married couples downsize after their kids leave home—but not Brigitte and Henning Freybe. They have upsized three times in the last few decades, adding ever more rooms onto their West Vancouver house to accommodate their acclaimed and still-growing collection of modern and contemporary art. It’s a diverse collection of some 325 works that span painting, sculpture, photography, video, installation, neon, and even hazelnut tree pollen by a raft of American and international artists, many of whom have rarely if ever exhibited in Vancouver. They have also acquired works by leading British Columbia artists, especially those associated with what has been dubbed “the Vancouver School.” Over lunch in their white-walled dining room, they speak with ardent appreciation of the artworks they have gathered together—and the people who made them. They mention two they have a particular interest in, British artist Tacita Dean and Vancouver’s Stan Douglas. Hanging behind us is Douglas’s digitally reconstructed nighttime view of Hogan’s Alley, a historic Black neighbourhood that was demolished to make way for the Georgia Viaduct replacement.

“There are risks the Freybes have taken in buying and living with artworks that are really ambitious from an artistic perspective.” —Eva Respini

“It’s a phenomenal collection,” says Eva Respini, the Vancouver Art Gallery’s director of curatorial programs (and one of the gallery’s two interim co-CEOs following the departure of Anthony Kiendl in March). Seated at a table in her office, Respini adds, “It has a personality in that there are risks the Freybes have taken in buying and living with artworks that are really ambitious from an artistic perspective.” Having arrived at the VAG in August 2023 from major cultural institutions in Boston and New York, Respini has seen her share of significant private art collections. The Freybes, she says, have chosen works “that are representative of an artist’s best output, that are of a scale and rigour and ambition that are of museum quality.”

After lunch, the Freybes tour me past works throughout a house that more closely resembles a cutting-edge art gallery than a suburban dwelling. Among them are two big and expressive prints by Ethiopian American artist Julie Mehretu; a “carpet” of metal plates by minimalist American sculptor Carl Andre; a text work composed of large black nails hammered into a white wall, conceived by Iranian-born, Berlin-based Nairy Baghramian; a mixed-media work whose principal components are black salt and white ice by Pier Paolo Calzolari, an Italian artist associated with the arte povera movement; and a cedar bark weaving by Lil’wat Nation artist Melvin Williams. A vision emerges that is expansive, eclectic, and intellectually challenging.

Henning and Brigitte Freybe photographed by Christos Dikeakos.

The Freybes began acquiring art in the early 1970s, initially from Ace Gallery in Vancouver and later at art fairs in Basel, Berlin, New York, and Los Angeles. One of their earliest purchases was Piaski III, a low-relief geometric abstraction by the late American artist Frank Stella. One of their most recent acquisitions is a complex installation on multiple paper panels by Andrea Carlson, a Chicago-based artist of Ojibwe/European descent. Brigitte, who as a young woman studied graphic design in Basel, Switzerland, and Munich, Germany, and later worked as a graphic designer in Vancouver and Montreal, suggests that her approach to collecting is intuitive. Certain works move her in ways she can’t always articulate. “I can’t say why,” she says with a self-deprecating shrug.

One thing she can say is that she and Henning must arrive at a consensus on a piece before they buy it. Henning, who immigrated to Canada from Germany with his family at the age of 12 and is now retired from a highly successful career as CEO of Freybe Gourmet Foods, says, “I have an amazing amount of faith in Brigitte’s judgement… She has a much better eye, an eye that is willing to live with the unusual, to live with something that is different.” Occasionally they will disagree over an artwork, in which case they won’t acquire it. What they always and emphatically agree upon, however, is that they do not buy art as an investment. “We never wanted to sell anything,” Brigitte says. They collect works they want to live with, works that grant them pleasure, interest, and insight every day. “We take it as an honour to be living with art,” they told Canadian Art magazine.

The Freybes and their collection are very much in the public eye right now. Earlier this year, the Vancouver Art Gallery announced the couple’s promised gift of 122 artworks, heralded as the largest donation of contemporary art in the gallery’s history. (Roughly half of the remaining works in their collection will go to their two children, who, Henning says, “have a strong interest in contemporary art.”)

Frank Stella, Piaski III, 1973, canvas, felt, paint on corrugated cardboard, Collection of the Vancouver Art Gallery, Promised Gift of Brigitte and Henning Freybe, © 2024 Frank Stella/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/CARCC Ottawa, Photo: Vancouver Art Gallery.

More than 30 pieces from the VAG gift are featured in Postcards From the Heart: Selections From the Brigitte and Henning Freybe Collection, which is on view at the gallery until October 5. Organized by Respini and curatorial assistant Andrea Valentine-Lewis, the exhibition highlights some of the most important works in the collection while also examining the ways it has evolved and some of its overarching themes. “One very strong thematic is material concerns,” Respini says. She gives the example of Tara Donovan’s minimalist cube, made out of hundreds of thousands of wooden toothpicks held together by friction, density, and gravity.

“Part of our life that’s fascinating is taking care of the art. You’re not there only to look at it. You are responsible for it.” —Brigitte Freybe

Some of the art the Freybes own can be difficult—visually, emotionally, and intellectually. Respini references Reliquaire, a photo-sculptural installation by French artist Christian Boltanski. Employing elements of light and darkness and, most movingly, the blurred images of children sourced from historical photographs, the work makes direct and painful reference to the Holocaust. It is, Respini says, “a tough piece to live with,” especially given that Brigitte and Henning are of German descent. (Canadian citizens of many decades standing, both were born in Germany during the Second World War.) “Brigitte has talked about this piece as a way for her to understand the Third Reich.… So for me this is a very important piece because it also marks something of their personal engagement and personal history.”

Left: Tacita Dean, Kippy Cloud, 2016, chalk on blackboard, Collection of the Vancouver Art Gallery, Promised Gift of Brigitte and Henning Freybe, © Tacita Dean, Photo: Fredrik Nilsen, Courtesy of Frith Street Gallery, London and Marian Goodman, New York/Paris/Los Angeles. Right: Helen Pashgian, Untitled (Column #5), 2010, formed acrylic, Collection of the Vancouver Art Gallery, Promised Gift of Brigitte and Henning Freybe, Photo: Vancouver Art Gallery.

Another demanding work is Sea-Cow Treaty (Spread), an assemblage or “combine” by Robert Rauschenberg, one of the most important American artists of the 20th century. Created in 1977, it brings together graphic and sculptural elements and a working water feature involving twinned taps running red and blue water into conjoined metal buckets. It is, Respini says, “almost a leitmotif for the collection because it does so many things as an artwork.… It is adventurous and a bit unexpected.” Then she adds, “That adventurous spirit of breaking the rules is very much in the spirit of the Freybes’ collecting practices.”

And yes, the couple acknowledge that a few of the works they’ve taken into their home require a degree of commitment many art lovers can’t or won’t muster. “Part of our life that’s fascinating is taking care of the art,” Brigitte says. “You’re not there only to look at it. You are responsible for it.” Henning notes that Sea-Cow Treaty was originally acquired by a renowned art collector in Los Angeles. She returned it to the commercial gallery where she had purchased it because she was unwilling to live with its many demands, including filling the two buckets with water, colouring one with blue dye and the other with red, mopping up the inevitable splashes, and constantly hearing the sounds the work makes. “We love living with it, and ironically the sound has an unusual feature,” Henning says. “When you walk away from it, you hear it in different parts of the house. And as you hear the sound, you see the image in your mind. So it is continually with you.”

Tara Donovan, Toothpicks, 2004, wooden toothpicks, Collection of the Vancouver Art Gallery, Promised Gift of Brigitte and Henning Freybe, Photo: Vancouver Art Gallery.

Rodney Graham, Pipe Cleaner Artist, Amalfi, ’61, 2013, painted aluminum lightbox with transmounted chromogenic transparency, Collection of the Vancouver Art Gallery, Promised Gift of Brigitte and Henning Freybe, Photo: Courtesy of 303 Gallery.

As for all that upsizing, the creation of space in their home for museum-sized pieces, Brigitte says, “We never looked at the idea of how we placed art. We just started buying it because we loved it.” Henning mentions a monumental 1983 installation by the Italian artist Mario Merz, a work whose components include sand, oil, and organic matter applied to two immense, wire-framed canvases. The Freybes could only display one canvas at a time in what was then their living room and eventually donated the installation in its entirety to McMaster University. Other large pieces have been incorporated more successfully into their house. An important sculpture by British Columbia artist Brian Jungen—a 10-foot-tall “totem pole” composed of stacked golf bags—called for the creation of a spacious, high-ceilinged stairwell during a recent expansion. An earlier sizable piece, a mixed-media work on canvas from Rauschenberg’s Hoarfrosts series, required enlarging a wall in the Freybes’ entrance hall and installing a skylight above it. “We had to stretch ourselves a little bit,” Henning says about the renovation that ensured the work was shown to its best advantage. “Placing the art in a way that gives credit to the piece and the artist is important to us.”

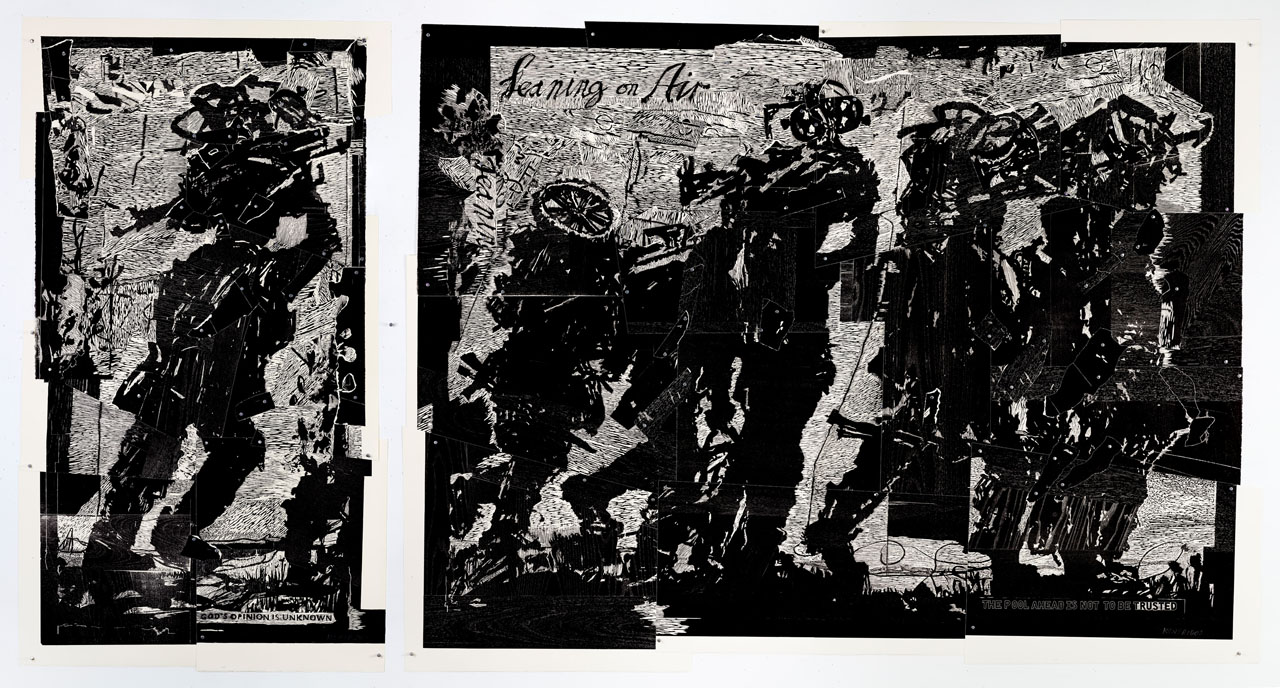

William Kentridge, Refugees (1. God’s Opinion is Unknown; 2. Leaning on Air), 2018–21, 26 woodblocks on 77 sheets of paper, aluminum pins, Collection of the Vancouver Art Gallery, Promised Gift of Brigitte and Henning Freybe, Photo: Thys Dullart, Courtesy of David Krut Projects

Brigitte believes that individual artworks must speak to one another in a visual dialogue that also conditions how and where they are installed. Along with the couple’s enormously generous commitment to the cultural life of Vancouver, their true belief in the importance of art, and their desire to give back to a place that welcomed them as immigrants many years ago, this belief has shaped the promised donation of their collection’s most significant artworks to the VAG. “I wanted the pieces to be together,” Brigitte says simply. “To be a family of art.”

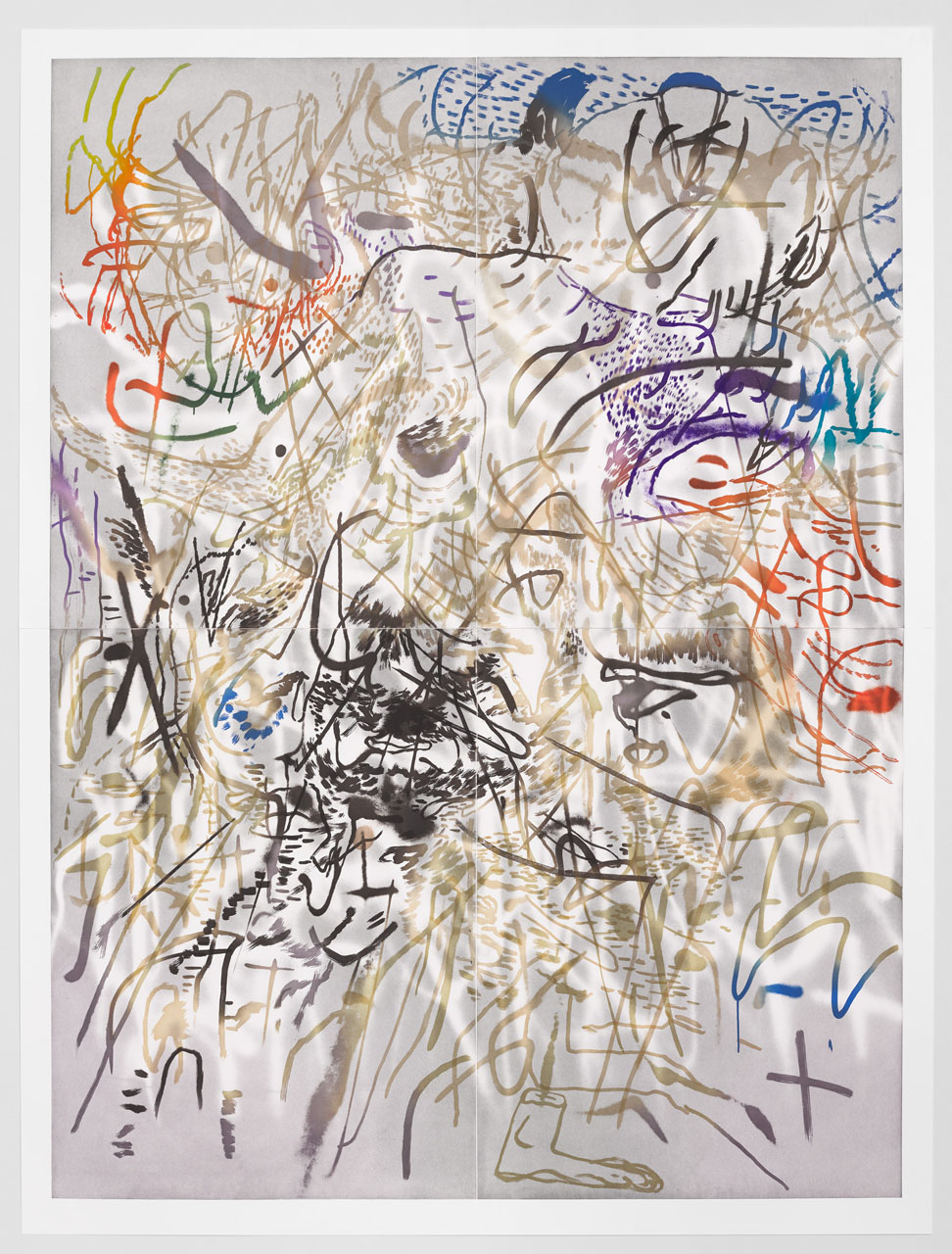

Julie Mehretu, Six Bardos: Luminous Appearance, 2018. 19 colour, 2 panel aquatint, Collection of the Vancouver Art Gallery, Promised Gift of Brigitte and Henning Freybe, Photo: Courtesy of Marian Goodman and White Cube.

Read more from our Summer 2025 issue.