Friends and colleagues lead us to unknown delights, stretching our minds and feeding our emotions. So when London pals invited us to explore one of their country’s hidden gems, we took the train to Bishop’s Stortford and travelled onward with them to nearby Perry Green and Henry Moore’s 50-acre Hertfordshire estate, considered the best place in the world to appreciate the work of the widely acknowledged greatest sculptor of the 20th century. Simultaneously, in his gardens, studio, home, and sculpture grounds, we peered into the artist’s heart and shared his influences.

Fortified by a picnic lunch of prosecco and poached salmon, we savoured a tour of Moore’s home, where eight people at a time are guided from low-ceilinged room to low-ceilinged room, taking in the sights of his many artifacts, including a bronze cast of the British Museum’s A’a god figure from Rurutu, Austral Islands (French Polynesia), as well as numerous dinner sets belonging to Moore’s wife, Irina Radetsky. It would seem that visitors are not the only ones who appreciate Moore’s work, as thieves who stole a £250,000 metal sundial and attempted to sell it for scrap metal for £48 were recently caught and jailed.

Moore’s home ambience, assisted by brightly coloured carpets from the 1960s and ’70s, includes Aztec and pre-Columbian sculptures; paintings by Courbet and Renoir; and Irina’s matchbox collection. It’s a captivating blend of the domestic (Moore made 30 fabric designs, which include Zigzag, Treble Clef, and Safety Pin motif curtains from the 1940s) and the outstanding (such as a study of a nude by Degas and a Picasso etching in the kitchen).

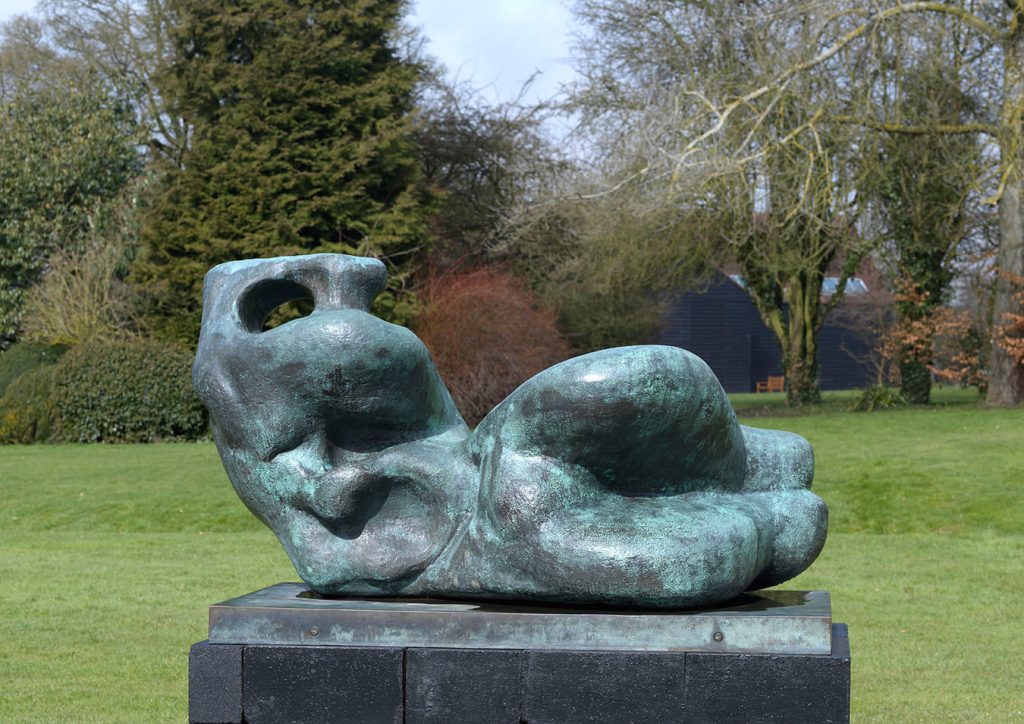

The artist’s generosity of spirit is immediately evident in his monumental bronzes and sculptures placed in the grounds, inviting amblers to touch and stroke such pieces as The Arch (1963–1969) or just gaze in awe at the symmetry of his 1966 bronze Double Oval silhouetted against the Hertfordshire sky. Three Piece Sculpture: Vertebrae (1968) invites circumambulation; the abstracted organic forms are evocative of movement, and they surprise from every angle. An outdoor setting was always Moore’s intended environment for his sculptures, which in the decades following the Second World War were sited in civic and public outdoor spaces around the world.

Also, Moore loved sheep. So much so that he sketched them throughout the seasons and stipulated that these gentle creatures should continue to roam the pastures, rubbing up against bronze sculptures at a certain level, where the lanolin in their coats leaves a glowing burnished patina that catches the sunlight.

Moore was fascinated by “mother and child” and “reclining figure” themes, particularly after the birth of his only daughter, Mary. And in the 17th-century tapestry barn, we glimpse how he might have arrived at some of his sinuous outdoor sculptures, channelled from long tapestries woven from his sketches of people sleeping unabashed, limbs defying gravity, loose with exhaustion in London underground bomb shelters. Moore had been gassed in France during the First World War, leaving him with poor lungs; one cannot help but peer into the heart of this artist, the seventh son of a coal miner, sketching in the shelters of the Second World War.

Artists are the sum of their life’s influences. In 1921, in Paris, Henry Moore saw a plaster of Chac Mool, the Toltec-Maya reclining figure; on a hill in Hertfordshire, we see the Mayan in Moore’s 30-foot long Large Reclining Figure (1984). In his acclaimed recent biography of Cezanne, author Alex Danchev quotes the artist’s credo: “To paint from nature is not to copy an object; it is to represent its sensations.” Henry Moore, sculptor: tranquilly observing his work, we understand, by osmosis, that nature is not copied but instead so masterfully realized at this hidden Hertfordshire gem.

All photos courtesy of the Henry Moore Foundation.