I’d come to the far edge of Vancouver Island to pick at my wounds. To punish myself with an early-morning ferry crossing and four-hour drive, then the solitary check-in to the resort teeming with couples in rubber surfing… costumes, is that the word? The stay at the lodge was nonrefundable, and I was too cheap not to go. Newly vaccinated, I was ready to leave our half-empty condo and see the world—even if it meant entering a cedar-accented room staged with chilled Champagne and a rose-petal-lined path to the bedroom.

A weekend of meals alone and ocean-kayaking with a group of couples had gnawed away at me. Now, on my last day, the ocean filled my eyes to the corners, making my problems feel small—in a way that felt needlessly accusatory. I thought I could hear whispering through the crashing waves: Don’t complain, don’t complain. I was healthy and still employed. Don’t complain, don’t complain. My friends had never liked my ex-fiancée, and they could barely conceal their relief. They no longer had to grumble impatiently as Eugenia, an aspiring food influencer, staged a dinnertime shot until the food grew cold. Don’t complain, don’t complain. My parents consoled me with platitudes. But they still seemed too fearful of the pandemic to enjoy the prospect of an outdoor wedding,

so their sympathy was leavened with relief.

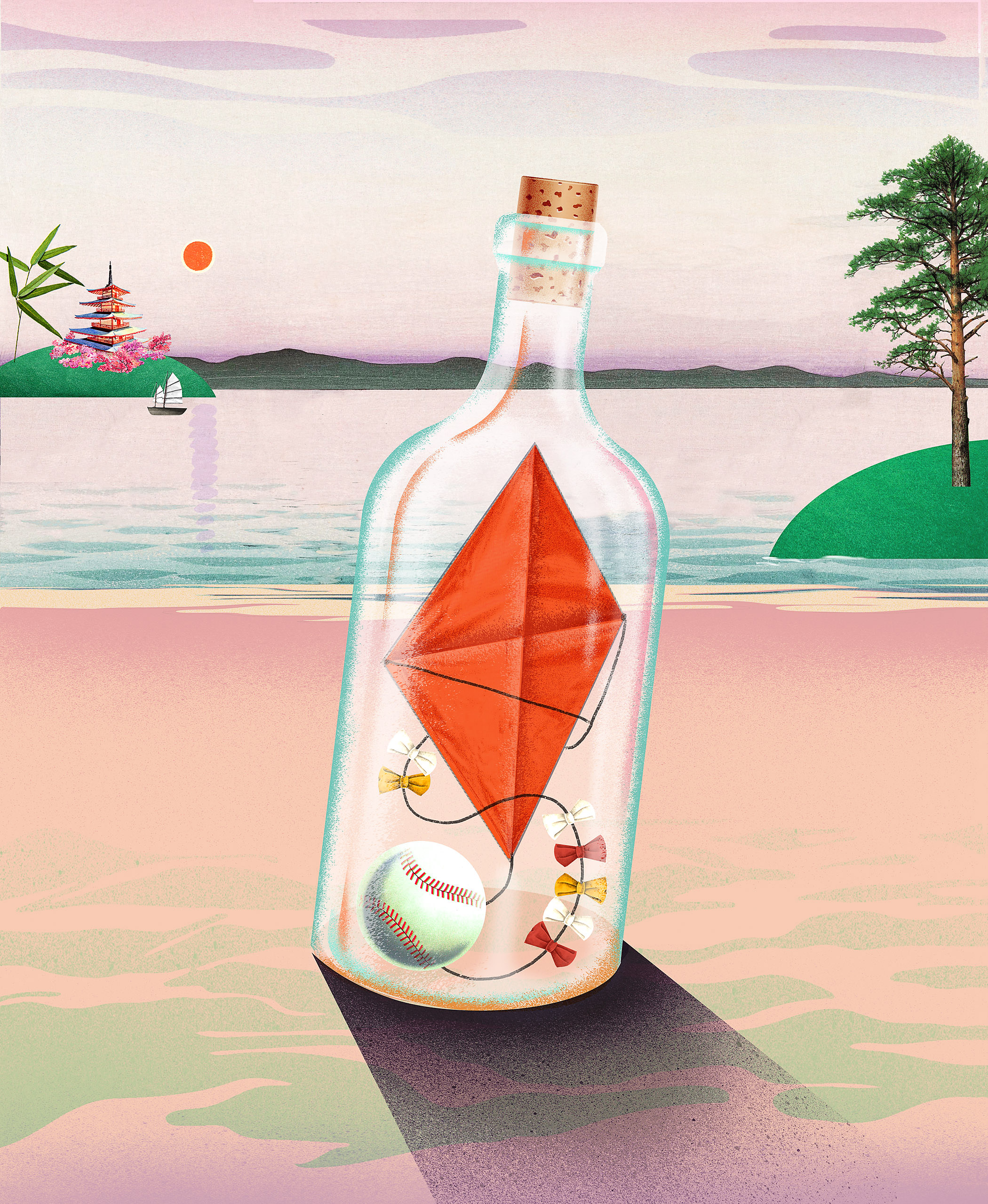

Turning back from the ocean, trudging to my car, I noticed it: a long-necked bottle. The glass had taken a yellow-green hue as though it had absorbed its colour from sea kelp. When I saw the Japanese lettering, I stooped down for a closer inspection. A screw-top cap was still fastened to its mouth. I picked it up and loosened the cap. There was a note inside that I fished out and rolled flat on my knee as I squatted down to read the neat block writing.

August 7th, 1995

Hello,

My name is Kaito Mori.

I am ten years old and live in Hamamatsu, Japan. I attend Kumakiri elementary school.

I am interested in video games, baseball, and kite-flying.

Please be my pen pal.

At the bottom was an address. As I reread the letter, the breadth of the horizon loosened its choke hold. I no longer felt as if the ocean had been taunting me. It needed me here to receive this wondrous oddity.

This note from a 10-year-old could save me. I knew it. But how?

On my way home, along the winding road, I felt the summer heat on my arms and drove timidly, frequently pulling over to let the locals barrel past me. By the time I made it to Swartz Bay, I had missed my ferry reservation. Waiting in my car for two hours, I scrolled through Eugenia’s socials. I’d largely avoided the fruits of her curated life. I was already familiar with the inspirational quotes about change and homespun odes to minimalism set to images of moving boxes and Eugenia’s new butterfly tattoo. But not the new boyfriend. In Eugenia’s late-morning brunch post, he wore $500 sneakers and day-old stubble. His image was already liked by dozens of followers.

The tightness had returned to my chest. I looked at that 26-year-old letter from Kaito Mori and removed it from the opened bottle. I took pictures of the bottle and the note, making sure the date on the letter was legible. I posted the photos online with the caption “Found at the Beach.”

There was no response at first. Not surprising. I had only 146 followers. Besides, it was a long weekend. I got a burger on the ferry and tried to sleep outside. As I saw the mainland in the distance, the oppressive reality of my Vancouver life beckoned. Sobbing at my keyboard as I approximated a 9-to-5 workday at home, in my shorts. Aggressively honking in traffic, growling at people pushing their shopping carts in the wrong direction down a one-way supermarket aisle. Zoom yoga sessions, microphone muted so I could fart freely.

When I returned to my condo, it was getting dark. There were five likes, seven reposts of my Kaito Mori post when I went to bed early, and a couple of comments of appreciative awe. By the time I woke up, there were dozens more likes and reposts. I turned off my phone, over the day, as the number swelled to thousands. All these impressions and engagements could have been yours, Eugenia, I thought to myself bitterly. If only you didn’t feel I was “closed off.”

During an office-wide afternoon Zoom call, my boss excitedly shared the news of my post to my coworkers. “Have you written back?” he asked me, echoing the sentiment of many people online.

“I’m working on it,” I said, with a forced smile.

I pinned the letter on the wall, over my desk, and that night I stared at it when I considered having more than two canned vodka seltzer drinks. What would Kaito Mori think about his Canadian pen pal if he saw me now? I wanted to live up to that kid’s expectations. Like the boy in Japan, I was 10 years old in 1995. I remembered how easy those days were. I wished to be that age again, excited about sports and video games and, I guess, kites.

The next day, I received a message from a TV producer who wanted to tape a segment on the letter. They were hoping to shoot it on the beach. The producer asked me for my cellphone number and told me to be at Spanish Banks that evening.

When I arrived at the beach, I needed a sweater. The sun was still near peak wattage, but a breeze had rolled in, and I could smell the barbecues from Jericho Beach. My phone buzzed. “It’s Tommy, the cameraman,” a voice announced. “I’m almost there.”

Tommy eventually rolled up in a van. He was older than I expected, with a white ponytail and a small chin. He wore cutoff jeans and a fanny pack. As I approached his car, he reset his face mask, which had dangled from one ear. “Tamzin is always five minutes late,” he said about the TV reporter who would interview me. He removed his camera and a black bag. “Mind if we get started?”

Until Tamzin arrived, we could shoot B-roll, the footage that normally plays as the reporter narrates passages of the news clip. Tommy set up his camera on the beach and asked me to stroll toward him, cradling the bottle against my chest. He assured me I wouldn’t look stupid on camera—I did.

“How was surfing in Tofino?” he asked, handing me a microphone and battery pack to wear. I ran the microphone’s cord up my shirt. “What makes you think I surfed?”

“I figured that’s what you were doing in Tofino.” It was when

he stepped back that I first saw two kids with a kite.

“I was on my honeymoon,” I told him. “By myself.”

My reply elicited a grimace from Tommy, as though I had revealed too much. “I shouldn’t have asked. Tamzin doesn’t like it when I steal her thunder,” he said before he noticed the kids with the kite. “I’ve got an idea.”

Tommy approached the kids, a brother and sister, flying the purple, diamond-shaped kite and asked them to let me fly it. “For the B-roll,” he said to their puzzled faces. The younger kid, the little brother, jerked the kite’s line in dismay, but his sister shot him a look of reproof. She took the kite spool from him and handed it to me.

A gust of wind caught the kite when I first took hold, and it looped in the air, then plummeted toward the ocean before I regained control. I wondered if Kaito Mori still flew kites, whether he was the kind of adult who maintained their childhood interests with fetishistic intensity, and I remembered how Eugenia had made me sell my Star Wars memorabilia before we moved in together.

Tommy crouched over his camera, pointing it from the kite to me. Then he stood up and gave me a thumbs-up. I handed the kite back to the siblings.

“Do you know they have a kite festival in Hamamatsu?” Tommy asked me. “It’s been going on for nearly five centuries.”

“So… since the start of the pandemic?” I joked.

“There’s an interesting backstory to the festival,” Tommy said, but before he could continue, Tamzin arrived. She wore white jeans and heels and had very white teeth, and completed the interview in under five minutes.

Tamzin’s final question was on everyone’s mind, now that 29,000 people had liked my story. Will you write back to Kaito Mori? I stammered out my answer, all the while remembering the letters my grandmother would write to me, as a child, from Kamloops. In every note, she would dutifully report on her garden and her cats. Tell me how you are, she always said. Even then I was too embarrassed to write back unless something special happened, like winning the spelling bee or scoring a goal at soccer. I preferred silence over revealing my less-than-brilliant self.

I felt that way when Eugenia texted me. She too had learned about my Tofino beach find. She was writing because she felt that enough time had passed. She hoped we could get together for a walk to “debrief.” I left her text unanswered. I couldn’t let her see me this way, like something left out in the rain by accident.

So I worked, then stayed at home after work, declining further media requests. By the end of the week, the story of the message in the bottle eventually reached Japan. In a video clip that was sent to me dozens of times, Kaito Mori was interviewed at his home in Hamamatsu. “When I saw the note,” he said in subtitles, “I instantly remembered the day my friends and I each sent a message in a bottle. None of us received a reply.”

In his own B-roll, Mori, who was now a civil engineer, shared a meal with his wife and two sons and dusted off a school portrait of himself at age 10. In that school photo, his mouth was curled in the same impish grin he wore in his thirties—and I felt proud of him. I know that sounds stupid. But in my mind, the joy of a childhood had been preserved within him alongside that message in a bottle.

The report added that Kaito Mori hoped I would write back. “Maybe I will make a new friend.”

A couple of days later, I received a call from Tommy. He wanted to know whether I’d seen the news clip. “Actually,” he added, “the reason why I’m calling is because my wife and I separated in the winter. Things weren’t working out. I guess she had the courage to do something about it.”

Tommy had been married for 27 years. He said that my remark about attending my honeymoon alone had affected him. But he had covered it up. He had been feeling bad about his curt response when he called. “It’s been a hard time,” Tommy added. “For everyone. But also for me.”

Feeling sorry for both of us, I asked him whether he wanted to go for a beer.

Tommy agreed to meet me in the park near my condo. I set up my folding lawn chair with my six-pack of vodka seltzers and waited for him to arrive. There were already other groups there: families with toddlers, hipsters in tight jeans, older couples on blankets. In the far corner, someone was strumming a banjo. It only took a pandemic to make me appreciate drinking in a park.

I caught Tommy’s van pulling up behind the park’s baseball diamond. He climbed out of it with a cooler bag slug around one shoulder and a lawn chair in one hand. We waved. I was ready to tell him that I had read up about the Hamamatsu kite festival. The legend was that the lord of the castle flew a kite to mark the birth of his son. Now, every May, people travel there to celebrate their newborn children and pray for them to have long, happy lives. I pictured Kaito Mori taking his own kids to the festival. That’s when I remembered being 10 years old, on the patio with my grandmother, sipping grape soda, my forehead glistening in the heat.

The normalcy of the past, I could almost reach it.

Read

Read