In October 1975, while he was still appearing on cinema screens as James Bond’s triple-nippled nemesis Scaramanga in The Man With the Golden Gun—a film that raked in nearly $98 million at the box office—Christopher Lee took a room at the Sylvia Hotel and prepared for a less auspicious project. An international star with an almost three-decade-long career behind him, Lee arrived in Vancouver, implausibly enough, to make his North American debut in The Keeper, a tax-shelter-funded oddity pasted together for less than $150,000 by a bunch of hippies from the Slocan Valley.

“Two weeks in English Bay, doing an easy job? I think that was really a big part of the appeal,” says Steven Drake, who was hired at the tender age of 15 to work in the film’s sound department. It was a family project for the budding musician. Younger brother Adam received his first credit as an assistant grip, mother Sally Gray was third-billed under Lee, and the project was written and directed by Drake’s father, Tom, an L.A. exile whose colourful past—prior to relocating the family to the draft-dodger’s dreamland of the Kootenays—included a stint as a story editor on the TV series Then Came Bronson. “We were complete amateurs,” Drake laughs. “What did we know about making a movie?”

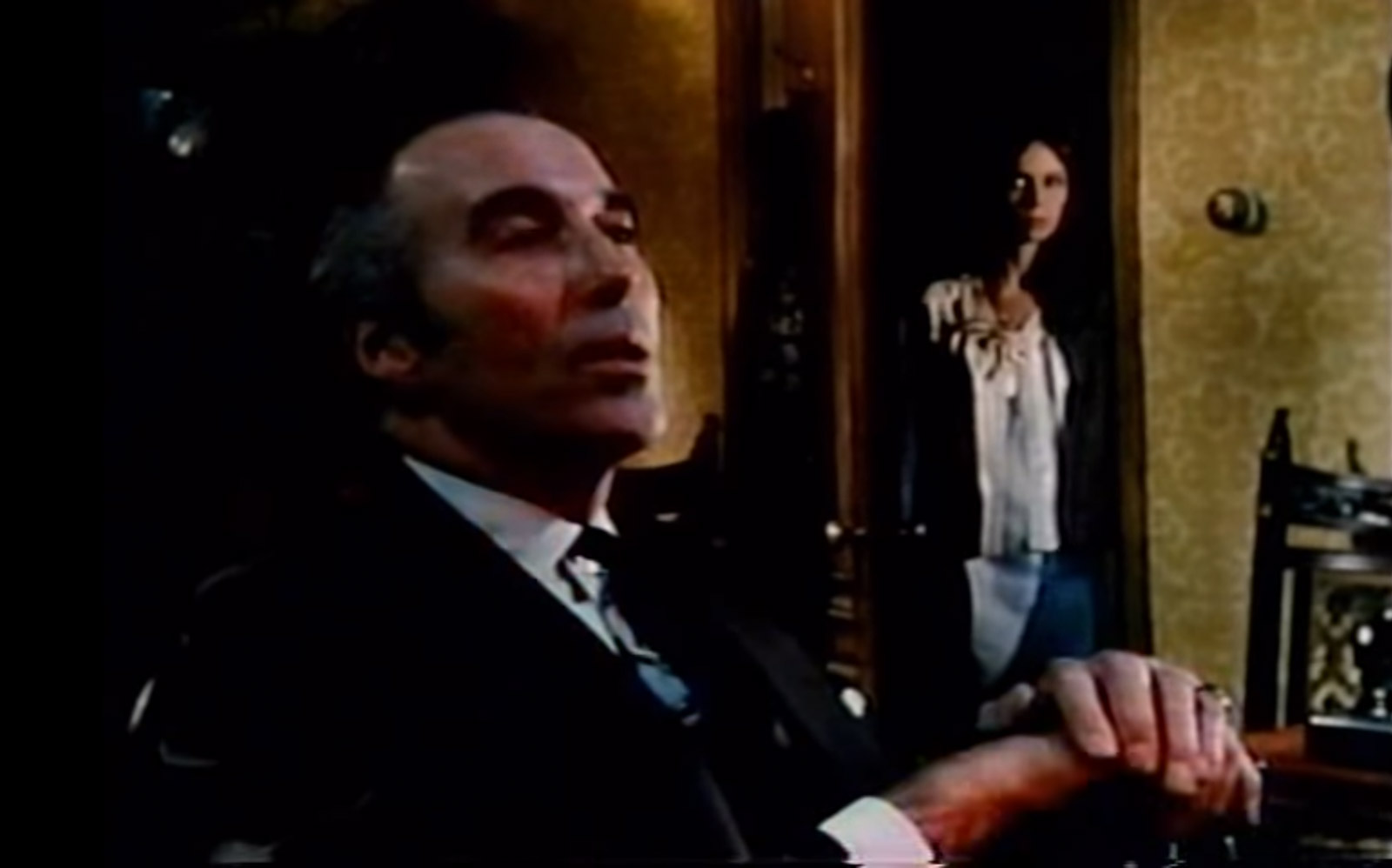

Viewing the forgotten film on YouTube, it seems they knew just enough to conjure an amiable 90 minutes of entertainment. Set in 1947 Vancouver, the film is, naturally, dominated by Lee in his title role as the director of the Underwood Asylum, a private institution (actually Aberthau Mansion in West Point Grey) where wealthy inmates submit to sinister mind-control experiments. A private dick tries to expose the Keeper’s racket, alternately aided and thwarted by some dumdum cops, a streetwise shoeshine boy, and an undercover agent working from the inside. Lee’s unflappable professionalism aside, it’s all endearingly terrible.

Cast member Bing Jensen offers a pithier assessment: “What a shitty movie!” he roars, reached at his Qualicum Beach home. “And all I got out of it was a pair of shoes. Nice shoes, though!” In 1975, Jensen was singing with the band Brain Damage, a sort of resident Grateful Dead to the Slocan Valley set, once described by Bob Geldof in the pages of The Georgia Straight as “psychedelic megalomania” (like he should talk). Jensen affectionately remembers Tom Drake as the “godfather” of the Valley’s alternative community. “One day he said, ‘We’re making a movie, and you guys are all gonna be in it.’”

With that, the Underwood Asylum was populated with members of the band and its entourage. Almost 50 years later, this is partly why a certain aura still clings to The Keeper. The film’s core personnel of radicals, freaks, and creative misfits would leave their fingerprints all over B.C.’s cultural map—and beyond.

Legendary experimental filmmaker Al Razutis was tapped for the film’s cheerfully daft optical effects, while Marv Newland’s animation studio International Rocketship Limited scored one of its first jobs with the title credits. And the role of private investigator Dick Driver went to family friend Tell Schreiber, whose kids Pablo and, in particular, Liev Schreiber would go on to conquer Hollywood. Jensen remembers five-year-old Liev (a.k.a. “Huggy”) running around when Brain Damage played its first-ever show at the Schreiber family farm.

Young Steven Drake received an expanded musical education as the assistant to soundtrack composer Erich Hoyt, another Slocan Valley neighbour, who’d later achieve renown as one of the world’s leading cetacean researchers. “That was my first direct experience of programming synthesizers and plugging in tape machines and recording stuff,” Drake recalls. “He’d just gotten back from the Arctic with an Arp 2600, which he’d taken out into the ocean to try to speak to the whales.” There were further attractions for a “young rock and roll kid.” Another Underwood Asylum inmate—she’s the one playing Go Fish—was later memorialized, rather explicitly, in the libidinous 1991 hit “Wendy Under the Stars” by Drake’s band, Odds.

And then there’s “the Kid.” Ian Tracey was still in elementary school when he received his first-ever credit as the film’s shoeshine boy. “I really loved Tom Drake,” he says. “Just a very warm and empathetic guy. He didn’t treat me like a kid at all. He just talked to me like a friend.” These days Tracey is one of the city’s busiest actors, perhaps most recognized through his collaborations with writer Chris Haddock on Da Vinci’s Inquest and Intelligence. His warm memories of riding the bus to work every day from Port Coquitlam will be potent to anyone who grew up under the more relaxed parental regimes of the ’70s. “I was my own man at 11 years old,” he says. “It was a real ragtag bunch of musician-actor types. I felt like I’d joined the circus. They treated me like their little mascot, and I just felt immediately at home. I loved it.”

As for the aristocratic movie star in everyone’s midst, all involved remember Christopher Lee as a gentleman whose most extravagant demand was a regular cup of tea. He generously praised Drake’s script in The Province, worked patiently with an inexperienced cast, and gave at least one young actor a pivotal lesson in the craft. “I remember it being so real,” Tracey says, recalling his big scene with the Brit legend. “It wasn’t like we were play-acting. I got brought to this really slow, still, intense place looking into the eyes of Christopher Lee, and I’m just soaking up his energy. I still remember that feeling. Everything else just kinda disappears. When that happens, that’s when you know—it’s working.”

All this because Tom Drake sent his script to Count Dracula’s agent. As cosmic improbabilities go, it’s a keeper.

This story is from our Summer 2021 issue. Read more Arts stories.