Medhi Walerski enters the studio, drops effortlessly to his knees, and moves into child’s pose, eyes closed, fingertips stretching purposefully forward. The dancers, who had been chatting and smiling, react immediately, deepening their own stretches, taking their cues from the man on the floor.

“Good morning,” he says, standing up straight, feet slightly apart, eyes still closed. “Let’s start by connecting to our breath, gently shifting our weight. Micro movement. Find energy through the body.”

He speaks quietly, gently. Demanding focus. As the stretches turn into exercises, his voice remains low, just loud enough to be heard over the rhythmic playing of the rehearsal pianist.

“Be greedy. Take time to be curious about your body.” The dancers move onto barre work. “Do what you need. I am not in your body. You are your own physio.”

Ballet BC has just returned from a break to begin rehearsals for the 2022/23 season. Walerski is leading today’s class as a way to both introduce himself to the several dancers (10 out of 14) new to the main company and establish the tone for the troupe: rigorous but fully supported.

“The studio is a sacred place,” he tells me when we meet again a couple of weeks later. “It is a safe space for us all to share, to explore—to be curious in our art. The energy that we bring into the room has an effect on everyone else.”

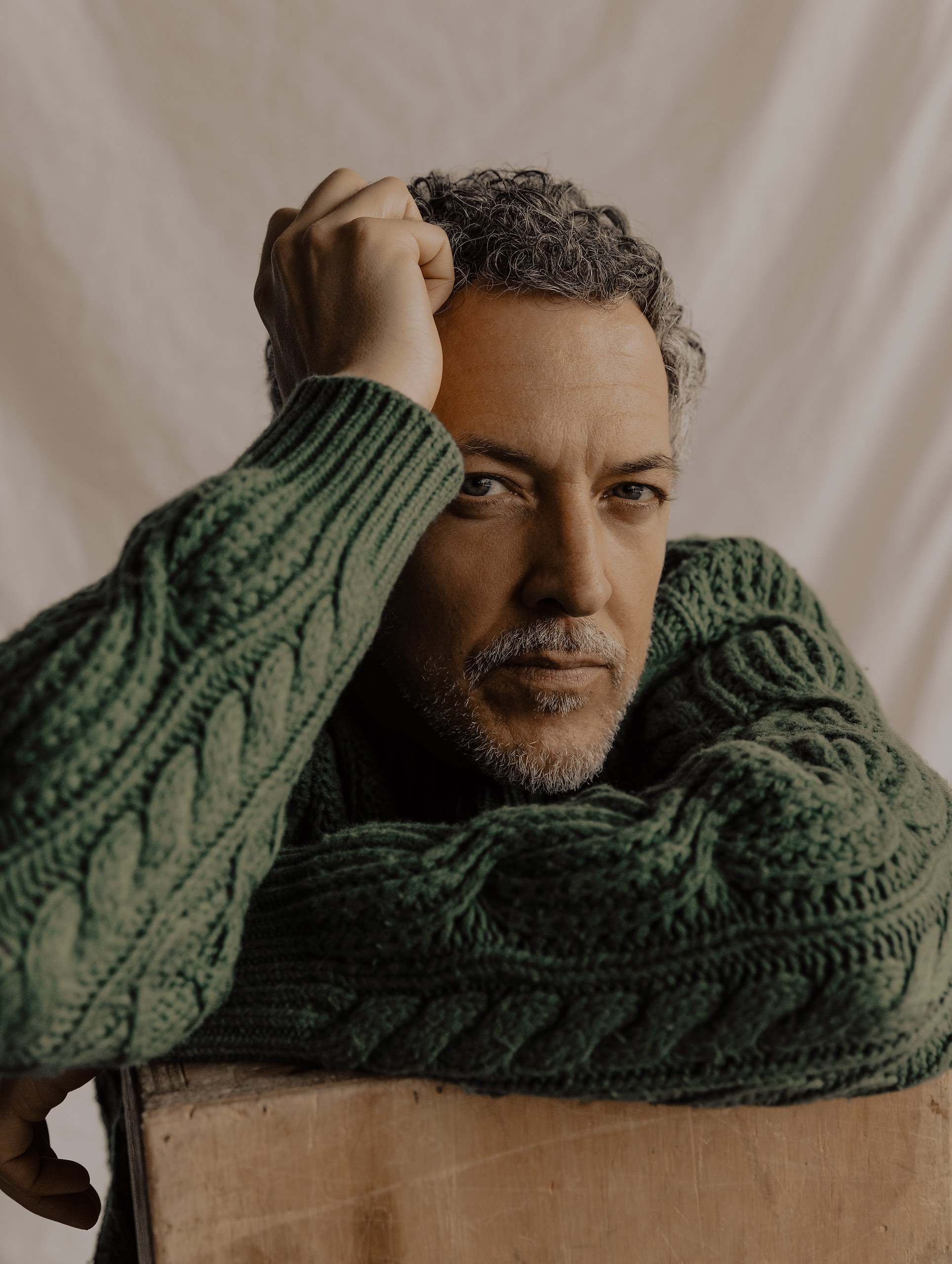

We are in his office. There is a standing desk, and sunlight pours through the window. I tell him how, even as a seated observer, I had left his class walking on air, feeling inspired and truly alive, and he thanks me in the same gentle, mellifluous voice, a decibel or two below the norm. Everything about him appears intentional, from the crease-free, loose-fitting linen suit and immaculate brown nubuck Birkenstocks to his piercing gaze that dares you to look away. The decades of dancer’s discipline inculcated since childhood have culminated in an easy charisma.

“I think I got into dance because there was this idea of connecting to the body through movement. It was very much a part of life at home. With my family, any celebration was an excuse for us to dance.”

Walerski took over as artistic director of Ballet BC in 2020, replacing Emily Molnar, credited with not only reversing the dance company’s ailing fortunes following mass layoffs and near bankruptcy in 2008 but also bringing it to wide international acclaim. Molnar, who had once been the company’s principal dancer, put her focus on the creation of new work by contemporary choreographers, including Walerski. She left Vancouver to become artistic director at Nederlands Dans Theater (NDT) in The Hague, where Walerski had worked as first dancer and then choreographer since 2001.

Changing jobs (never mind countries) in 2020 did not go as expected. In February, Walerski was in Vancouver to recast Romeo + Juliet, a major work commissioned for the company by Molnar and first presented in 2018. He returned to the Netherlands in March to finish packing up his life and move to Vancouver full time. The day after he landed in Europe, the world went into lockdown, and his new position took on a completely different focus. Overnight, his job was to make sure there was still a viable arts organization postpandemic.

“It was about creating the structure that would allow the company to regroup,” he recalls. “I kept moving forward, doing my job online for a few months, and everything arrived here before me, furniture included. I had an apartment here—my life basically was in Vancouver—but I was in Europe.”

It was challenging, he admits. His nights became his days, filled with online meetings, but he remained excited about the work. “I felt that it was just so important for us to come back in the act of creation,” he says. “To try and balance the amount of destruction happening in the world by continuing to create.”

He was born in France, spending two years in Africa as a small child when his electrician father took a job in Senegal. His was, he says, a “simple family” with no artistic background. He had lots of hobbies—soccer, tennis, piano—but dance was the one that stuck. “I think I got into dance because there was this idea of connecting to the body through movement. It was very much a part of life at home,” he says. “With my family, any celebration was an excuse for us to dance.”

It was a small town, and he was the only boy taking ballet, but his parents never made an issue out of it. “My parents were really open, and so I just saw myself as part of a group and I was enjoying myself. I don’t know if my gender was really defined at that point. I was a human being dancing with other human beings.

“Even my being gay was never something we discussed at home as being different, so I felt incredibly supported,” he adds. “That’s huge.”

At 16, he was in Paris, studying at the Conservatoire National Supérieur de Musique et de Danse de Paris, supported for five years by subsidies from the French government. He loved it, embracing the structure, the discipline, and a schedule “that almost drew the boundaries of human potential—mental and physical.”

He began his professional career at the Paris Opera Ballet, an organization known for its uncompromising ethos and entrenched hierarchy. He stayed only a few months.

“It’s an incredible institution, but at the time I was looking for a different space. I was looking for diversity in terms of mentality and culture,” he explains. He left for Alsace to join Ballet du Rhin for a season before moving to NDT, where he says classically trained dancers from multiple nationalities worked together, everyone considered equal.

“In classical ballet, it’s still pretty exclusive,” he notes. “I think we are changing the narrative these days, and that continues to evolve with this new generation. They have much more of a voice.”

He began choreographing almost immediately, combining it with his dancing career until, at 34, his body protested. “I ripped my Achilles on stage,” he explains, noting my involuntary grimace. “Awful, yes, but at the same time, it was the best thing that could have happened to me—I was pushing my body to the extreme. I see it as a catalyst for my transition as an artist.”

Now 43, Walerski is expanding his creativity again as an artistic director, commissioning new works and curating Ballet BC’s domestic and international programs. Outgoing executive director John Clark notes that Walerski was in his mind as a potential recruit when Molnar shared her plans to leave, having not only witnessed him create for the Vancouver company but also worked with him directly on a presentation at the 2018 Edinburgh Festival Fringe. “The vision and connections were clear,” Clark tells me. “He really knows how to inspire dancers.”

Sarah Pippin and Rae Srivastava in rehearsal.

If Molnar successfully introduced Ballet BC to the world, Walerski hopes to bring it to the attention of more people at home. The company is committed to connecting with communities across the province, engaging with Indigenous choreographers, and inviting Vancouverites who may hear the word “ballet” and think of swans and sugar plum fairies to experience vibrant contemporary dance for themselves.

Fundamental to Walerski’s own sense of purpose is the artistic endeavour. Everything we discuss comes back to this central idea: the importance of creation, the willingness to be exposed and vulnerable. Most significant, perhaps, is believing in the process instead of focusing on the outcome. At a time when arts organizations struggling to survive are falling back on crowd pleasers and pop culture, under Walerski, Ballet BC is doubling down on being a home of original and challenging artworks.

In practice, that means when a choreographer is commissioned to create a piece in Vancouver with the company, the resulting work premieres as part of that season’s program. How the program will work as a whole is unknowable. Walerski gives the visiting artists free rein. Molnar, Clark says, was more hands on.

“My responsibility as an artistic director is to strengthen the structure and environment that allows the artist to flourish,” Walerski insists. “As I am also an artist, I do not advise or interfere with their vision. I love freedom, and in order for freedom to be activated, you have to offer autonomy. The process might be really challenging and shitty sometimes, but what comes out of it can be magic.”

And if it’s not?

“It’s part of their journey,” he says, matter-of-factly. “We are afraid to fail, we only want successes—but if you focus on creating a success, it’s too hard. You have to allow failure to be part of your creativity.

“And the beauty of what we do,” he adds, “is that it is alive. Every time you remount your work you have the ability—the freedom—to change it. That’s why I love what I do.”

Back in the studio, it’s the last day of rehearsals before Walerski casts the dancers who will perform his own work, the duet Silent Tides, in the November program. The atmosphere is intense as the pairs repeat sections of the work again and again, Walerski intermittently checking a video of a previous performance, making adjustments where needed.

“Use your eye as an extension of your body,” he directs. “Almost as a limb.”

The pairs have been created “strategically,” the company’s rehearsal director tells me, and even to my untrained eye, I can see the choice is close to being made. Nevertheless, Walerski takes the time to watch everyone, offering encouragement and praise.

“All of us appreciate validation, and at the start of your career, you need that validation more,” he says, when I note the glowing smiles a simple “yes, good” from his lips elicits. “I have been reflecting on that over the past few months,” he adds. “I never want to create an environment that doesn’t support or uplift the dancers. To be in the studio, to constantly look at yourself and access parts of your humanity that are vulnerable…

“This,” he adds, after a thoughtful pause, “is the work I respect deeply. The work of artists.”

Read more from our Autumn 2022 issue.