Nearly everything, according to Gabor Maté, is connected.

In March 1987, the light falling across early cherry blossoms was dimming when Maté, then a family doctor in his early forties, arrived at a delivery room in Vancouver General Hospital. His patient, a 38-year-old woman at the culmination of her third pregnancy, paced back and forth across the room, pausing for contractions that were strong but not decisive. Labour had been long and frustrating, and she worried it wasn’t progressing fast enough—that something might be wrong.

Maté entered the room, said hello, then walked unruffled to the opposite corner where he sat down in a chair, pulled from his bag a volume of Marcel Proust’s In Search of Lost Time—the rambling novel of more than a million words—and began to read. His patient, remembering when she had grappled with the same sentences, thought to herself that if her doctor was reading Proust, things couldn’t be all that bad. Her baby was born shortly thereafter.

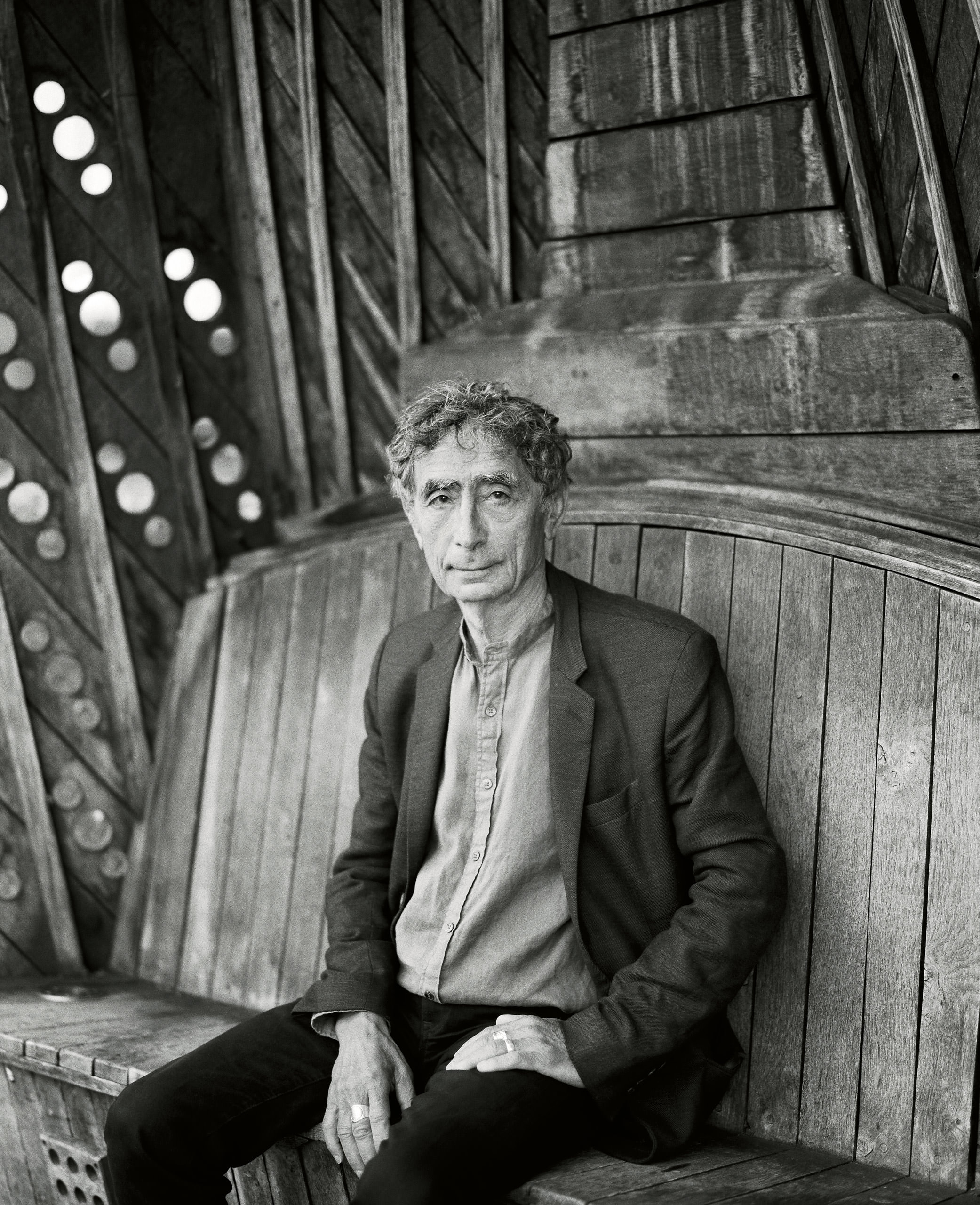

Thirty-five years later, I arrive to meet Dr. Maté as he returns home from swimming. Dismounting from his bike in a rumpled salmon-pink T-shirt, his front path framed by lush oxalis and twin laurel trees, he beckons me into the kitchen, where he fetches soup from a deli container, clearing me a place to sit at the table by brushing aside a handwritten note from his wife, the artist Rae Maté whose paintings peer out from the walls alongside vibrant Indigenous masks. His face, at 78, is penetratingly serious under shaggy eyebrows and a mop of grey hair, but he moves between the fridge and the stove with the bounce of an athlete.

Since we last met, Maté has become one of the leading medical voices on addiction, trauma, and harm reduction, working with mentally ill and addicted people in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, speaking out for safe drug-use facilities such as Vancouver’s Insite and pushing the boundaries of research on psychedelic drugs. His worldview is rooted in the conviction that trauma—which he sees as a psychological rupture that leads to a lasting separation from the self—is at the root of addiction, mental illness, and everyday self-destructive behaviour.

The most famous passage of In Search of Lost Time arrives a few pages into the first volume (Maté remembers the page number with uncanny accuracy), when Proust’s narrator swallows a spoonful of a madeleine cake soaked in tea and is immediately struck with an overpowering emotional response he can’t identify. Closing his eyes and straining to understand the experience, he realizes it is not the tea and cake itself causing the feeling but a moment of lost joy from his own childhood, echoed and dissociated by time, springing back to life.

The idea that our current experiences can only be properly understood in the context of our childhoods, our unconscious emotional associations, and the burden of our old joys and wounds is at the heart of Maté’s present work. In his latest book, The Myth of Normal, he furiously smudges the borders between binaries of health and illness: mind and body, past and present, patient and symptom, individual and society. Our narrow obsession with one or the other, he writes, blinds us to the overarching conditions that make our society as a whole sick or well.

Maté neglects his simmering pot on the stove to tell me how he might go about reforming medicine. “The first thing I would do is to educate the doctors,” he says. “Doctors don’t have a clue about the mind-body unity. It’s obvious.

“It’s just a scientific fact. It’s not a brilliant, penetrating thought that I’ve had. It’s documented and documented and documented. I mean, right now, doctors are educated in an ideological stance. They think they’re studying science—and they do study great science—but to the extent that excludes the broader perspective, it’s a very narrow ideology.”

Walk into a clinic for multiple sclerosis, cancer, or diabetes, Maté points out, and it’s unlikely your physician will ask about your childhood, your relationships, or your past experiences of abuse or neglect. But, he believes, these questions are essential to understanding disease, alongside blood tests and cardiograms. He imagines a world in which doctors work alongside therapists and social workers to address the biopsychosocial roots of disease.

“The average physician does not get a single lecture about trauma, even though trauma is the prime dynamic documented in most mental health conditions, in addiction, in many physical conditions,” he says. “They don’t get a single lecture!”

I remind Maté of his soup. As he fills his bowl at the stove, he talks me through a central metaphor from his book. Raising children, or living our own lives in our modern world, can be like doing horticulture on the moon, he says. He tries to kick a sliding kitchen drawer closed with his right ankle, but a pile of pots he has failed to put back into place blocks the way with a clatter.

“How worried are you that I’m going to float away right now?” he asks, returning to the table.

“Not very.”

“Why not?” He raises an eyebrow.

“I suppose because that’s not something that I’m used to happening.”

“A thing called gravity,” he says, poking the air with his spoon. “But if you landed on the moon, all of a sudden I might float off, right? But if I know about it, I can wear heavy boots or something. I can compensate for it. If we’re aware of something, we can do something about it.”

This is, for Maté, the myth of normal. If we believe our feet are planted on Earth—a world in tune with our natural needs and well-being—then disease will seem like a random accident, something that assaults us from outside. But instead, we are gardening on the moon—a modern world full of distraction, dissociation, inequality, loneliness, and cycles of trauma. The gravity of our lives doesn’t suit our delicate roots.

Maté wants to be clear: bringing the social and psychological into medicine is not the same as pseudoscientific wishing-away of illness, nor does it mean blaming people for their own hardship. It is, he says, about acknowledging the hard fact that the whole person—circumstances, relationships, events, and experience—matters. Though none of this stops him from saying things that are breathtakingly controversial.

“Medical science shows that mind and body are inseparable,” he says. Then, with a conspiratorial twinkle: “Not everyone who represses their emotions will get an autoimmune disease, but everyone with an autoimmune disease represses their emotions.”

This seems as good a time as any to tell Maté we’ve met before. I tell him the story of my birth 35 years ago, including his therapeutically nonchalant reading of Proust.

“I had no idea!” he says, as if he might have recognized me had he squinted harder. But then adds, “But when you said that, I thought, ‘Who else besides me would do that?’”

I was born a year before Maté’s youngest son, whose birth story forms a tenderly personal undercurrent in The Myth of Normal. Maté describes himself during these years as addicted to work, sometimes shouldering 15 deliveries a month to avoid grappling with his own inner demons. He reflects on how his own trauma—accumulated as an infant in Nazi-occupied Hungary—may have been passed down to his son, through pathways as concrete as distracted fatherhood and as subtle as stress during pregnancy.

The idea that children might be so deeply vulnerable to the environment in which they take root sticks in my mind. I read Maté’s book late at night, flipping the pages with my thumb as I bounced my own newborn son to sleep swaddled on my chest. Is there any way he could be spared the ill effects of growing up in an imperfect world?

“You can’t change the culture, but the relationship with the parents and the relationship of the parents to one another is the ocean in which these kids swim,” Maté tells me. “If you deal with your own stresses, you’re going to build a buffer and a template that will help negotiate this very difficult world, right?”

What would he do if he were a new father today? “I would put everything secondary to the raising of my kids, knowing that if I got the first few years right, I can relax afterwards. I would ask my past self, not what I want from them or for them: who I want them to be.

“I would ask them what are their needs as human beings,” he says. “I would be driven by that.”

Read more from our Autumn 2022 issue.