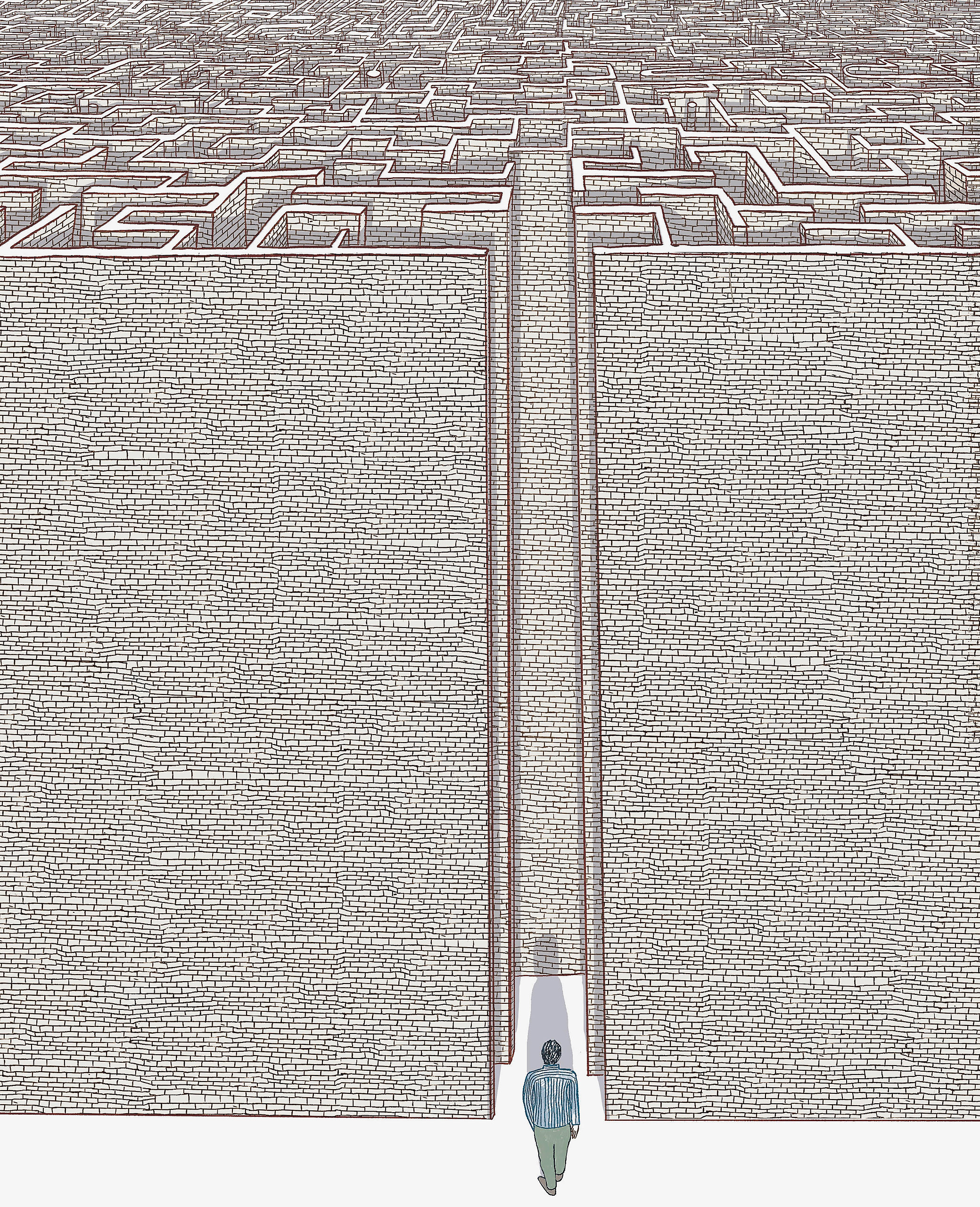

In 1965, Martha and the Vandellas released “Nowhere to Run”—an upbeat, dancey number about a woman in a relationship she just can’t quit. “I got nowhere to run to, baby, nowhere to hide” might also be the investor’s refrain for 2022: by mid-June, Wall Street’s benchmark stock market index—the S&P 500—had entered bear market territory, meaning it had declined more than 20 per cent from its record highs of early 2022. Anybody with an RRSP has been feeling the pain of this toxic relationship for many months now.

In a normal bear market, there might, indeed, be somewhere to hide. Usually that’s bonds—which is why the traditional advice from financial planners is to keep 60 per cent of investments in stocks and 40 per cent in fixed income. Bonds are safe, boring assets that protect you from the turbulence of the market. But that’s in a low-inflation environment. In 2022, inflation was running at 7.6 per cent in Canada and 8.5 per cent in the United States by the end of July. In a high-inflation environment, the purchasing power of bonds’ future cash flows erodes each day.

And don’t get us started on that supposed inflationary hedge everybody was talking about last year: bitcoin. By mid-June, bitcoin was down 67 per cent from its all-time high last November (or as some wise guy on Twitter pointed out, if you’d invested $10,000 last October when Matt Damon released his “Fortune Favours the Brave” ad for Crypto.com, you’d have $3,696 in bitcoin today).

Stocks, bonds, cash, crypto: Nowhere to run. Nowhere to hide. No hope? Well, not according to Dana Fleming, the CEO and founder of Vancouver boutique investment firm Vision Wealth Management. Fleming got her start in anthropology (receiving a BA from Stanford University) before moving into management consulting and ultimately financial planning in 1998. Over the past 24 years, she’s seen her share of market turbulence, but her mantra remains the same: stick to the (financial) plan.

“I always say to clients, ‘Where’s your boat headed?’ I try to use very simple language to help them picture what’s going on.” Fleming argues that it’s critical to have something to measure against when the waters roil—to see how far off course you actually are. “That’s the part people miss all the time—they just go, ‘Oh, my God, the world is blowing up.’ My statements are down 5 per cent, 10 per cent, 20 per cent. But that, to me, offers zero context. If you’ve been growing your portfolio and are ahead of your markers, you will have built a buffer. And those buffers are there for a reason—because we will go through these cycles.”

Fleming learned the importance of buffers early on. “I started investing at the age of 16, through my mother’s penny stock account on the Vancouver Stock Exchange,” Fleming recalls. “I had two core strategies. One was, ‘here’s some seed money—you can buy whatever crazy thing you want, but if you lose it all you’re out, no more playing.’ And two, I had what I call ‘core investing,’ which was just dull, boring stuff—but good stuff.” Eventually, she made that hobby her life’s work.

For Fleming, the missing ingredient in a lot of financial planning—and the reason she launched Vision in 2009—is a lack of investor education. In addition to an in-depth bi-annual newsletter, Fleming and her team send out an e-alert on “really horrific days,” detailing what they saw on the market or in particular economic news. During the financial crisis of 2008–09, Fleming brought in every single investor who was retired or within five years of retirement and went through their numbers.

“And I showed them: ‘You are okay. You’re still on plan.’ We definitely managed that period as well: we were very high in cash, because I didn’t like what I was seeing in the subprime market.” This year, she says, a lot of the discussion surrounds the once-sacrosanct balanced portfolio: “We’ve had to educate clients about the value in being more equity biased at this time.”

Staying the course—sticking to the plan—assumes that things “return to normal.” And eventually they do: the average bear market lasts about 289 days, or just under 10 months. But as John De Goey, a portfolio manager at Wellington-Altus Private Wealth, wrote in a May Globe and Mail op-ed, no one really knows how long a downturn will last. “There are plenty of ‘long-term’ Japanese investors who still haven’t seen their stocks regain their 1989 levels,” he noted. “No doubt, some of them may have had the legitimate psychological makeup to stay the course for 33 years. Unfortunately, many of them are dead now.”

As for Fleming, she and her team think that for Vision pooled funds, “there’s still an opportunity to finish the year in at least neutral territory, if not positive.” In 2022, “neutral territory” might be somewhere to run to—or to borrow a familiar expression, “any port in a storm.”

Read more from our Autumn 2022 issue.