For the worlds of art and architecture, the most famous and influential modern dwelling ever built in British Columbia is not a mansion in Eagle Harbour, a villa in Shaughnessy, a West End penthouse, or even a Gulf Island getaway. It was not designed by Ron Thom, Peter Cardew, or the modest homebuilders whose output is now overhyped by realtors as “West Coast Moderns.” The house is on a tiny street off West Vancouver’s Marine Drive, provides barely 2,000 square feet of living space including but one bedroom, was constructed for $30,000 on a $9,000 lot for a client on a modest salary as an art school instructor, and has rarely been visited by anyone outside of Vancouver’s tight visual arts community.

This post-and-beam house around a small courtyard is a little miracle, an explosion of creativity and craft that Arthur Erickson conceived in 1964. His ambition is demonstrated by the massive rough-sawn cedar beams cantilevered out from their supporting posts in extensions six, even 12 feet past their anchors. They hang in midair as interrogations, reaching out toward the flanking forest—they foster anticipation, that most modernist of emotions. Coupled with the evolving design of Simon Fraser University—underway at the same time—when it was published in magazines and newspapers, this house established Erickson’s global reputation.

Gordon Smith used the lower floor of the studio for his wild abstract painting, while Marion worked her looms in the upper loft. Photo by John Fulker from the Erickson Family Collection, courtesy of Arthurerickson.com.

The house was designed for Erickson’s friend and previous client, the abstract painter Gordon Smith and his weaver-wife Marion, a childless couple who were each other’s best critics and muses. Smith II gets its name because it is the second studio-residence Erickson designed for the couple. The previous house was much simpler and bare-boxy, his first commission after starting his practice with Geoffrey Massey in 1953. It was destroyed long ago.

Nearly lost, not so long ago, Smith II—both house and garden—has been restored to full glory in time for the 100th anniversary in 2024 of Erickson’s birth. Along with word of the $60-million improvement of SFU’s public spaces and the complete rebuilding of the UBC Museum of Anthropology’s Great Hall, this heralds a precious legacy secured.

Photo by John Fulker from the Erickson Family Collection, courtesy of Arthurerickson.com.

I was a frequent visitor to the house when Gordon and Marion lived there, bringing fellow critics and architects from around the world to marvel at this interplay of wood and glass on concrete decks, a pinwheel of innovation set on a promontory above the Pacific. Nearly all these visitors left in awe: of the multiple layers of design, the paradisiacal garden, and the warmth of our hosts. Despite the seeming chaos of his daubed, knifed, and brushed canvases transforming images of forests and seashores, Gordon Smith had high standards and rejected some of his finished paintings on paper. Later he would cut these rejects into 10-inch-square pieces, graciously presenting them as gifts to visitors as they left, unsigned mini-Smiths condensing the majesty of the larger works.

On a visit a dozen years ago, when Gordon was over 90, I told him I was disturbed that his plans were to gift his house and garden to a cash-hungry local university or art gallery, which would likely lead to its destruction or, perhaps worse, bowdlerization by subdividing the property. Born near Brighton in 1919 but relocated to Winnipeg with his mother and brother during the Depression, Smith replied forcefully in his mid-Atlantic accent, summoning both his British charm and Manitoban bluntness: “The house should be demolished—it has served its purpose, in its own time and place. We need to get on with life, so it should go.”

Photo by Ema Peter, courtesy of Measured Architecture Inc.

Why he didn’t have this temple pulled down in a fit of high modernist pique is a tale of the generosity and patience of key players in Vancouver’s visual arts and architecture scenes. But first a tour of Smith II, to understand what was at play then. The driveway passes through a stolid patch of tall trees, then curves down and around to the house. To the right is a 1980s standalone studio designed by Russell Hollingsworth, which allowed the artist to produce much bigger canvases, work on more than one at a time, and separate his painting activity from the living space. Amidst the verticals of the trees, the house is a contrast in layered horizontals, especially the boards that edge its seemingly flat roof, then blithely proceed far past their supporting walls and columns, what Erickson and his staff called “flying beams” (he extended this design idea at Robson Square, UBC MOA, and many of his houses). The courtyard at this home’s heart is approached through a near-entry carport, the outdoor space small and simply appointed, with “stobs,” or wood block pavers, flanking a rectangular pond with just a trickle of water to nourish water lilies, irises, and rafts of water lettuce.

Smith II’s confounding complexities begin with its entry, an indirect route next to the original, smaller double studio for Gordon’s easels and Marion’s looms. Explaining his career-long interest in compressed and indirect entries for his buildings, Erickson once told me, “Never give away the architectural plot.” Similarly, the house turns out not to be flat: each of the four wings edging the courtyard is a few steps higher than the previous, the roof line rising in accordance. Erickson’s original design even included exterior steps up out of the bridging single bedroom on the fourth wing, so the “stacked square spiral” of the four-sided house plan could be walked a second time outside—on the roof, in the trees. The upper rooms lining the courtyard have walls that are nearly all glass. Drawing on their curatorial acumen, the current owners have installed a horizontal Gordon Smith diptych from their collection, which can solely be appreciated from the courtyard, this home’s essential outdoor “room.”

Arthur Erickson was the first Canadian to win the Gold Medal from the American Institute of Architects, and Smith II was part of his citation of honour.

Vancouver native Erickson understood how deprived we are of natural light come wintertime, so he extended the glass walls to almost absurd degrees, and Smith II is his West Coast riposte to those most famous glass houses, Mies van der Rohe’s 1945 Farnsworth House outside Chicago, then Philip Johnson’s 1948 Connecticut version. This transparency also works in summer because a ring of retained trees provides a first line of shade. Before its recent renovation, the kitchen was small and cheerily white-walled. It has now been repainted a forest-echoing shade of green, a choice the Erickson family finds questionable but understandable. The living room is linear to compensate for its narrowness, with sheets of glass on the courtyard side, the same on the other looking out onto the garden and Salish Sea beyond.

Photo by Ema Peter, courtesy of Measured Architecture Inc.

In 1986, Arthur Erickson was the first Canadian to win the Gold Medal from the American Institute of Architects, and Smith II was part of his citation of honour. Even so, this house is unprotected as a heritage site. The Smiths were distressed by the dismal fate of the house designed by Gordon’s UBC colleague and painting mentor Bertram Charles Binning—when completed in 1941 it was arguably the first International Style modernist house in Canada. Similarly childless, Bert’s widow, Jessie, had tried to donate it to UBC to use as a salon for students, artists, professors, and architects but reversed course to avoid its being sold. It was eventually gifted to a charitable trust, resulting in a tragicomedy with a rotating cast of bumbling municipal, nonprofit, and provincial actors. In 2015, the Binning house was purchased by a private buyer, who is trying to convince the City of West Vancouver to let the property be subdivided, despite its status as a National Historic Site. Watching its fate, Gordon Smith shifted his opinion. In his mid-90s he came to understand that only private patrons could be trusted to save the house for perpetuity. But who?

The past three years have seen enormous activity by the new owners and their builders to bring the house and garden back to mint condition.

He found his answer close to home. Selling his art through Equinox Gallery for several decades, he was pleased with the best sales of his long career and their huge mountings of his large canvases. Owner Andy Sylvester soon became more than a gallerist—a trusted friend and confidant. Sylvester’s partner in life is former Vancouver Art Gallery chief curator Daina Augaitis, who describes the Smiths as “the most delightful people,” admiring “the enormous respect and love they showed—a light touch when passing each other.” Marion had died in 2009, but Gordon lived on in the house for nearly a decade, before dying at age 100 in 2020.

Photo by Ema Peter, courtesy of Measured Architecture Inc.

The past three years have seen enormous activity by the new owners and their builders to bring the house and garden back to mint condition. Augaitis has reinvigorated the garden, a creative process that links to her childhood on a tobacco farm near Tillsonburg, Ontario. Over her career as an independent art curator, head of visual arts at the Banff Centre, then at the VAG, she never had more than a few pots on balconies as a garden. Assisted by architect Liana Sipelis, Augaitis has proven herself a rigorous and enlightened gardener: radically trimming aggressive laurel hedges, changing ground cover plantings and patterns, adding bright punctuations of new flowers in a cutting garden, and even establishing a brace of Nicotiana sylvestris (flowering tobacco), a marker of her Ontario youth. “I have become a different kind of curator,” she jokes.

With no heritage funding for this non-designated site, the couple had to pay for restoration, so they turned to an architect they trusted—Clinton Cuddington of Measured Architecture—who they had worked with before. Cuddington describes Smith II’s design as “seeming rational at first but actually possessing many more idiosyncratic, romantic moments.”

The living room bridges from a rock outcropping to the concrete garden decks. Photo by Ema Peter, courtesy of Measured Architecture Inc.

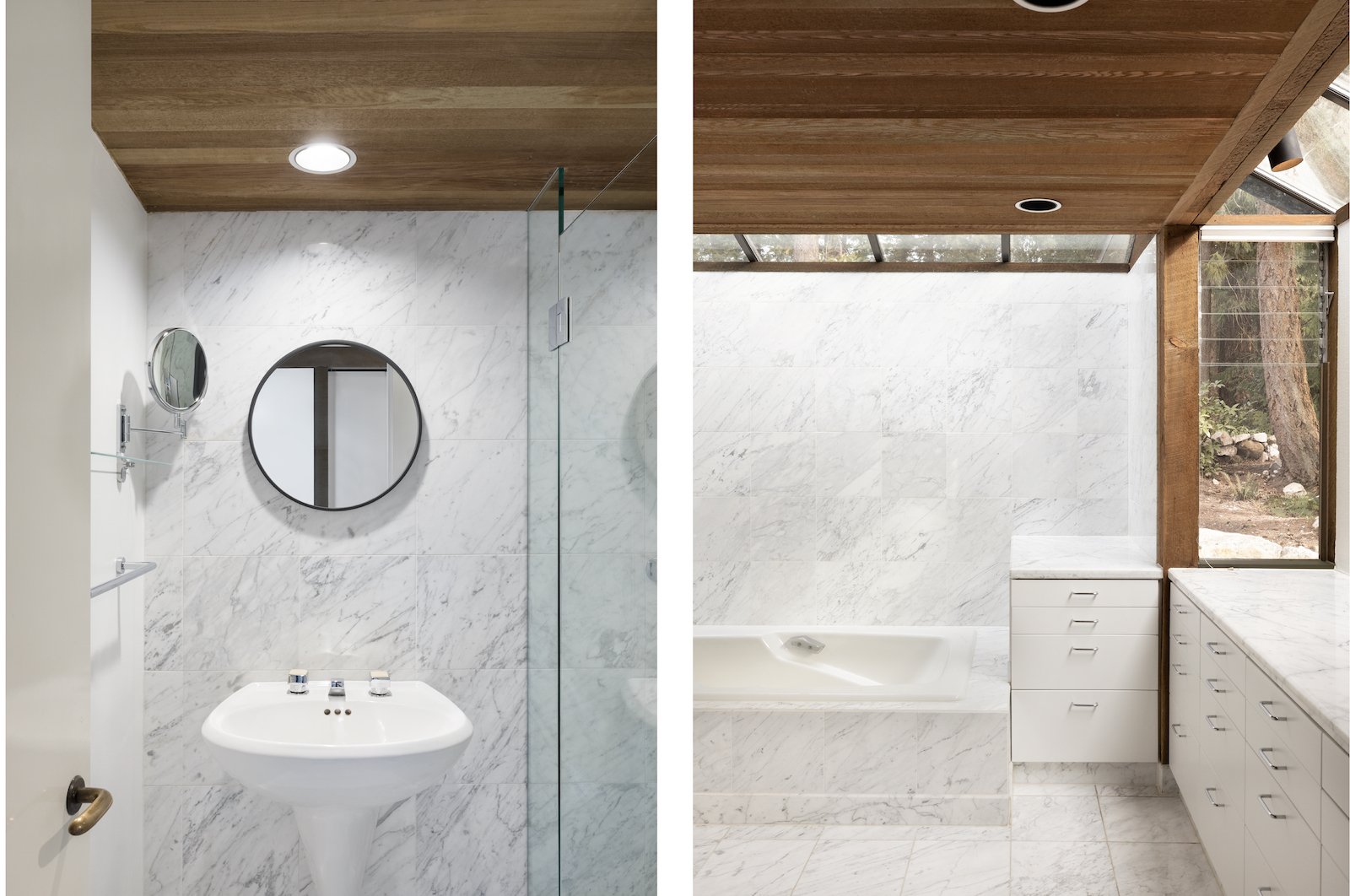

According to the architect, the commission required extra doses of humility and “knowing when to stop.” One challenge with the restoration was that it was impossible to maintain the house’s architectural character while adapting it to contemporary energy needs, meaning wearing sweaters in winter and taking most high summer meals on the decks, just as Gordon and Marion did. The bridge structure supporting the living room exhibited rot and had to be partly rebuilt, some windows were replaced, the kitchen and bathroom were updated, and a long-needed new roof had to have its slopes reset to reduce standing water, which was to be accomplished without changing the house’s iconic profile. The result is a kind of subtle plastic surgery in wood and glass.

Most of the handgrabs Gordon installed to help navigate the house when mobility faded were retained: “They are now part of the house’s history,” Cuddington says. Those extravagant cedar “flying beams” had required preservation with a brine solution once or twice a year, an onerous regular slog, increasingly difficult for an aging owner who did his own maintenance. Without Erickson’s permission or advice, several decades ago Gordon decided to have the wood stained a dark forest green. In protest, the architect did not set foot in the house for several years but eventually relented. Cuddington views the loss of the glowing exterior textures of wood as part of its provenance, so removing the coatings was never an option.

Erickson’s stacked concrete decks anticipate Robson Square. The orange wire-frame Corallo chair was a gift to the Smiths from writer/artist Douglas Coupland. Photo by Martin Knowles Photo/Media.

Augaitis and Sylvester know how important this house has been to members of Vancouver’s visual arts and architectural scenes, and will allow occasional access to them, as well as to students and design buffs from around the world. A highly successful arts fundraiser has already been held in the renewed house and garden. One of the most frequent visitors at Smith II over the decades has been novelist and artist Douglas Coupland, who lives in a Ron Thom house five minutes away. The Smiths were friends and mentors to him at all stages of his career, and there are many other Vancouver artists, writers, and architects who can say the same, including me. I am in total agreement with a blunt statement Coupland made when I told him I was writing this article: “Arthur Erickson’s house for Marion and Gordon Smith should be declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site.”

Read more from our Autumn 2023 issue.