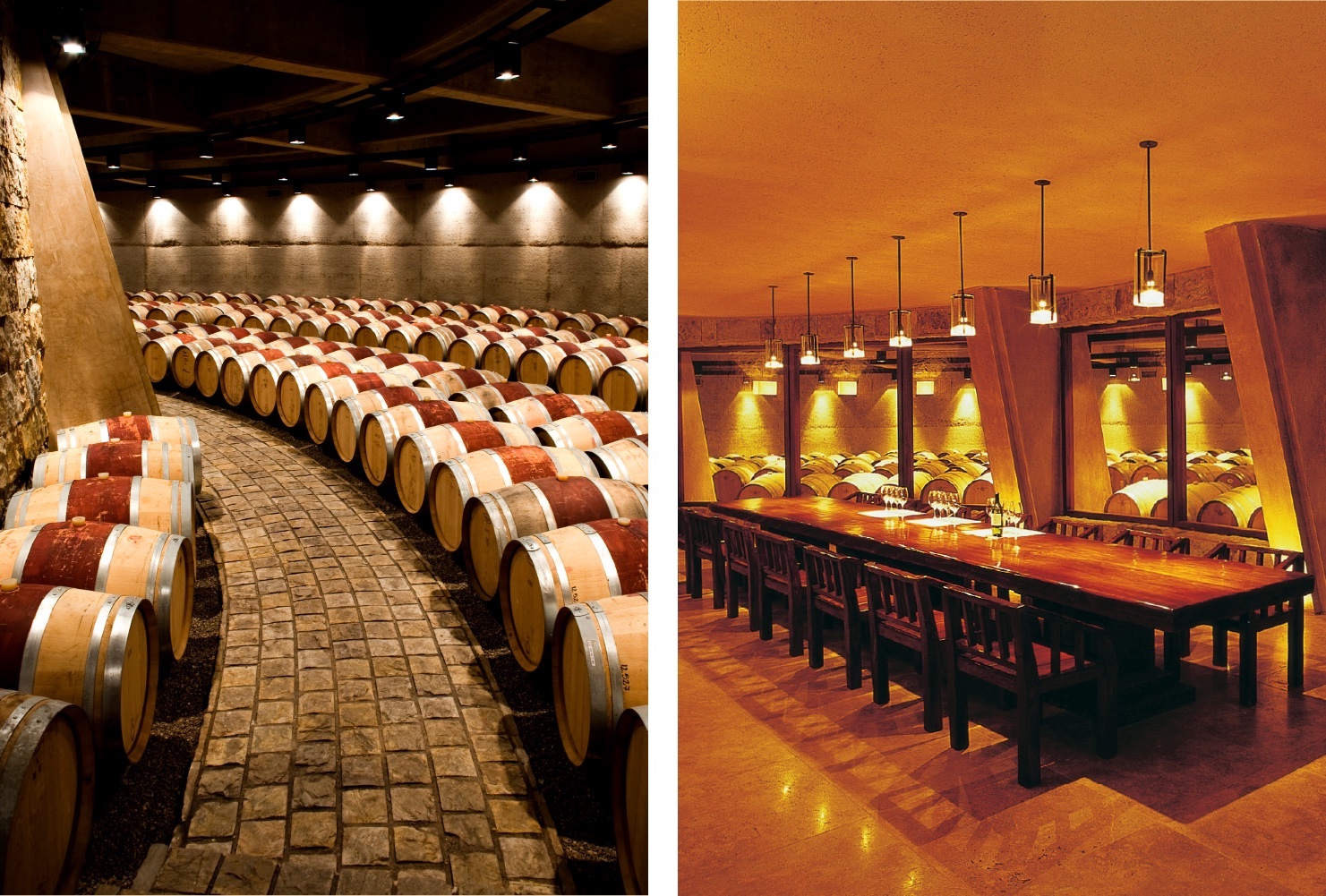

I didn’t meet the amazing Catena sisters when I first went to Mendoza in 2007, but I did visit their winery. An extraordinary structure, pyramidal and tiered, Catena Zapata sits in the shadow of the Andes nearly 1,000 metres above sea level, surrounded by vineyards, some higher still. It looks like something out of an adventure story and is, in fact, designed to recall ancient Maya architecture.

It isn’t hard to picture Laura or Adrianna, fourth-generation Catenas, as intrepid adventurers. Both have questing spirits. While making a wide range of internationally recognized wines is most people’s idea of a full-time job, Laura is also an emergency-room doctor, and Adrianna is a historian.

Catena Zapata vineyard and winery. Photo by Horacio Paone.

Then again, this is clearly a family in which nobody understands the word “can’t.” Nicola Catena was an Italian immigrant who planted vineyards in 1902. His son Domingo Catena withstood the travails of mid-20th-century Argentina—inflation, military governments—and the death of his wife, Angélica Zapata, and father in a car crash and kept the business going. He had begun sourcing grapes from La Consulta, a cooler region, but it was Domingo’s son, Nicolás Catena Zapata, who took on the challenge of elevating Catena wines in every sense, planting vines at altitude to avoid the stewed-fruit notes and alcoholic blast of hotter, flatter regions.

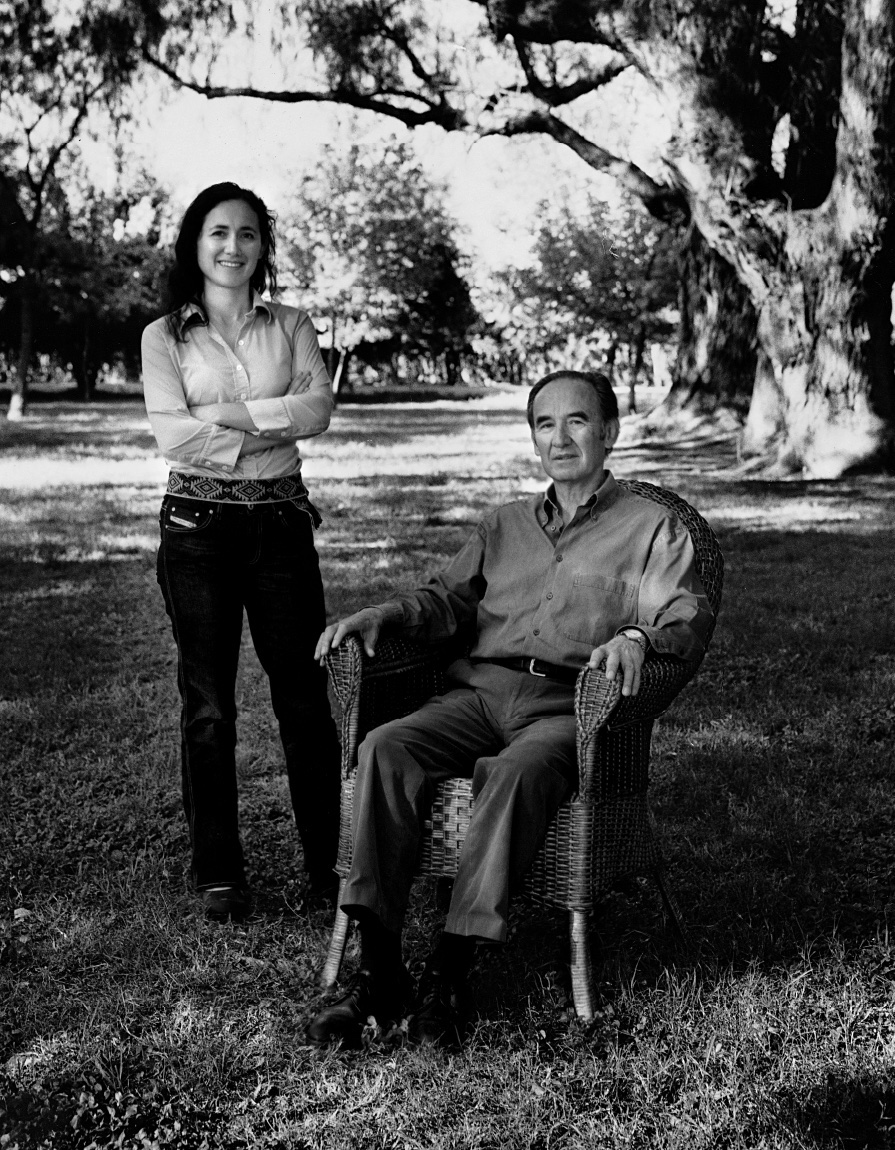

“My father is like a teenager,” Laura says of her octogenarian parent. “He is open to everything.” I don’t think he’s the only one. It’s early 2023, and Laura is in Canada to show her wines and talk about her new book on Argentina’s signature grape, Malbec Mon Amour, co-written with Catena’s winemaker, Alejandro Vigil. The book is like its author: digressive, knowledgeable, and tremendous fun.

Laura Catena and Nicolás Catena Zapata.

Laura showers me with interesting questions, all discussed in the book. Did I know malbec was the most planted variety in Bordeaux at the time of the famous, and still recognized, 1855 classification of the best estates in order of quality? And that the water in Mendoza’s vineyards comes from canals dug by the Indigenous peoples before the conquering Spanish arrived in the 16th century? Otherwise, Laura says, “the Spaniards would have found a desert.” The book contains stories of Eleanor of Aquitaine championing malbec when she became England’s queen, as well as details about individual vineyards.

In person, Laura talks about how the family’s revolutionary focus on high-altitude malbec has since been copied by almost everyone. “In the early 1990s, 80 per cent of vineyards were in the east of Argentina and 20 per cent in the [high] Uco Valley. Now it’s the reverse,” she explains. “I’m happy because the wine is better: fresher, more mineral. But what about all those people whose livelihoods depended on the wine industry?”

Barrel room and tasting room.

The Catenas are trying to make criollas—ancient grape varieties the Spanish settlers brought with them—better known. “But I think of them as ours because they’ve been here since the 1600s,” Laura says. “And they grow in the east.”

She offers a taste of one called La Marchigiana, which is gorgeous: deep apricot in colour, dry, yet perfumed, it is clearly a varietal that deserves to have its profile raised. I also try three malbecs from individual parcels of the famous Adrianna vineyard, which sits at nearly 1,500 metres. All are superb, but they taste surprisingly different from one another, bearing out Laura’s claim that malbec can convey le gout du terroir (the taste of terroir).

“The way I see malbec is like dark chocolate. I don’t think anybody ever thinks of moving on from dark chocolate.”

Neither she nor Adrianna, studying science and history respectively, had intended to join the family firm. But when I met Adrianna in London last year, she told me about Madre Coraje (Mother Courage), the foundation she has set up to assist women in viticulture. “With lots of farmers leaving the land, it’s important we work out what the women need to stay.” Like her older sister’s interest in criollas, this is a clear-eyed mix of altruism and self-interest: an understanding that, just as the health of the soil will affect what ends up in each bottle, so no winemaker, however successful, ever really operates alone.

As if they didn’t already have enough to do, the Catena sisters have also founded an institute to document the minute differences between terroirs, altitudes, and microbes in the soil. Phylloxera, the louse that destroyed European vineyards in the late 1800s, had no impact in Argentina. “I like to say that Argentina is the Old World for malbec because we have the ancient pre-phylloxera selections,” Laura says. “Our family has an isolated vineyard that preserves hundreds of cuttings—unique genetic material existing only in Mendoza.”

Adrianna Catena.

Is Argentina too focused on malbec, I ask Laura, a little cheekily since the Catenas’ international fame is so wrapped up with the grape. “The way I see malbec is like dark chocolate,” she muses. “I don’t think anybody ever thinks of moving on from dark chocolate. Why? Because it’s delicious to the human palate.” She continues, “Nobody ever says that Burgundy should move on, because pinot noir from there is so delicious and so diverse.”

Her attitude toward that other region so famous for le gout du terroir is both admiring and a little envious. She points out that studies on malbec are broader and wider ranging than anything in Burgundy, but she is aware that Argentinian malbec, as the brash newcomer, is more in need of help. “I don’t have 400 years to work things out like Cistercian monks.”

Familia Antigua.

I did not realize, when I first saw that extraordinary winery back in 2007, how well its strange beauty reflects the family who created it. There were no Maya in Argentina—like the Catena family, the structure is an interloper that doesn’t just decorate but enhances its new surroundings. Built around the millennium, it is intended as a gesture of gratitude to precolonial South America, and, perhaps, as a testament to what can be achieved with energy, courage, and an open mind. Inside, of course, it’s a state-of-the-art winery: a combination of past and present, science and history—as well as a great vantage point from which to survey the terrain.

All photos courtesy of Bodega Catena Zapata. Read more from our Spring 2023 issue.