On an April day in Vancouver, the street shimmers and steams as the sun shoulders its way through the remnants of a spring storm, a petrichor-promise of blue that animates the surroundings. As if some unseen director suddenly whispered “Action!,” people materialize from everywhere—walking dogs, strolling babies, riding bikes. But from the patio of a Kitsilano coffee shop, excited expectation isn’t what I see.

Instead, it feels like a memory of urban innocence, a snapshot of a world transformed. Like many of those who experience things never thought possible in our lifetimes (scientists recently admitted being stumped by sea temperatures that have spiked into “uncharted territory”), I peer through the lens of an Earth changing so fast that no amount of data or analytical savvy can deliver providence.

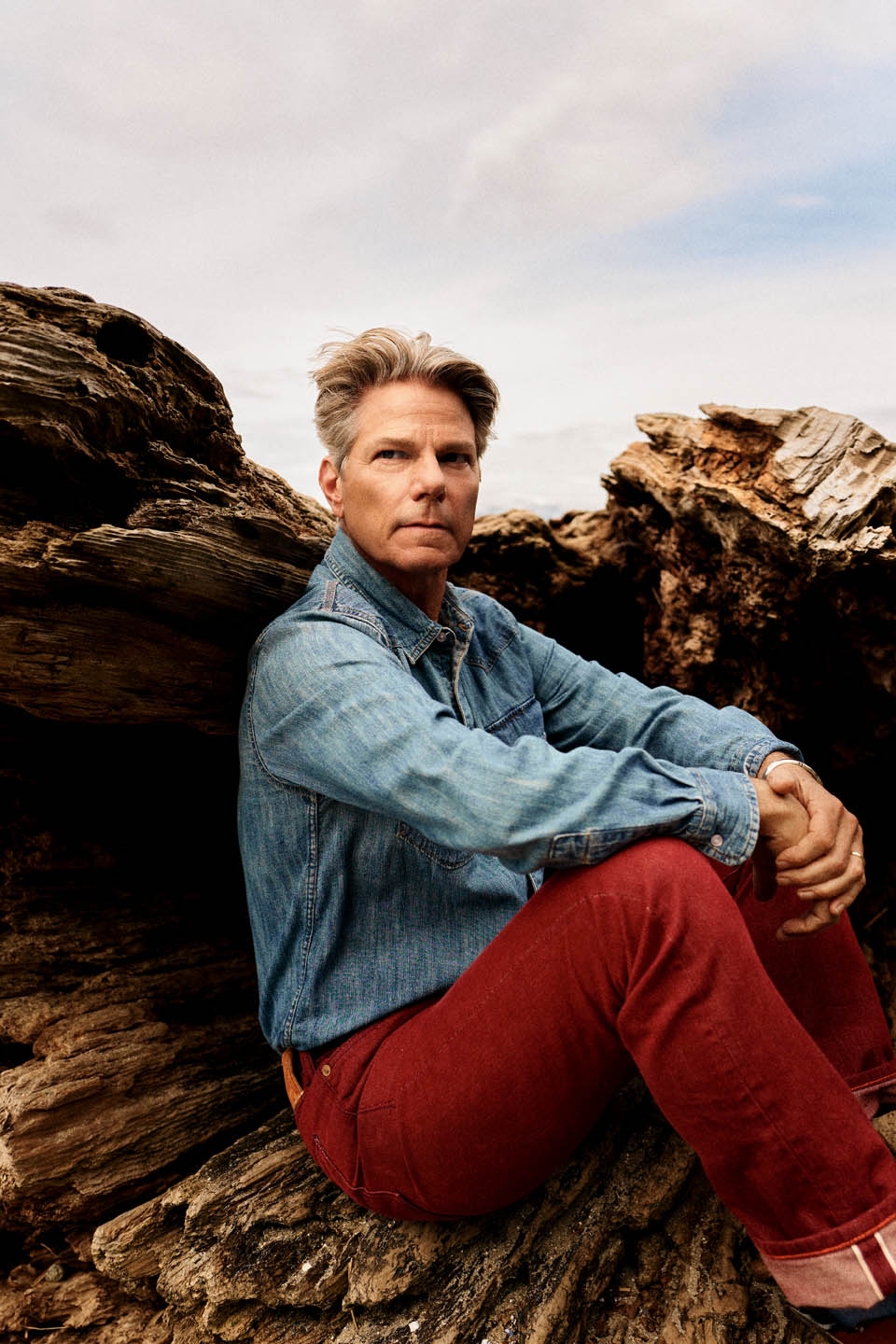

My companion, author John Vaillant, a big-picture kinda guy celebrated for painterly renderings of minutiae, shares this fraught point of view. As those of us who live in B.C. are made Argus-eyed by recent climate disasters, we’ve found ourselves contemplating the fate of our wooden homes—each a parched bomb of petrochemicals—in the advent of, say, a heat dome, a fire, and a 30-knot wind. Neither malicious nor macabre, it’s an honest slice of planetary zeitgeist.

“We’re just kind of rolling the dice now,” he says. “Us and the climate.”

This hypothesis comes from Vaillant’s latest book. Fire Weather: The Making of a Beast uses the apocalyptic May 2016 wildfire (nicknamed “the Beast” by firefighters) that consumed much of Fort McMurray, Alberta, as a springboard to larger interconnected themes of humanity’s relationship with fire. Rich in detail and far-reaching in scope, Vaillant’s trademark blend of research, imagination, and contemplation piles another superlative onto the Fort Mac fire’s list of firsts: the highest temperatures and driest conditions ever recorded in Alberta’s boreal forest in May, the first complete evacuation of a town of 90,000 in North America, and Canada’s costliest-ever loss of property. And add this: no book has laid bare a destructive wildland urban interface fire with the kind of historical, chemical, atmospheric, and human precision as Fire Weather. Vaillant’s previous creative nonfiction, The Golden Spruce and The Tiger, are acclaimed benchmarks of the genre. Fire Weather, an equal masterpiece of aggregation and integration, additionally bears a timely message from the future—one that took seven years to craft and left Vaillant traumatized and exhausted. Embracing the sun, he leans back to talk about the book’s genesis.

“The way it unfolded was surreal—a major industry threatened and an entire town just disappears under this enormous cloud of smoke. I was afraid for those people.”

He learned about the fire on Twitter, he says. “The way it unfolded was surreal—a major industry threatened and an entire town just disappears under this enormous cloud of smoke. I was genuinely afraid for those people.” Even days after they were all safe, he couldn’t stop thinking, “If this can happen in early spring where the land is frozen and car-sized blocks of ice are still sitting on the banks of Athabasca River, it can happen anywhere.” It was pure fear, he explains. “And this book is a journalist’s response to that fear, a humanistic need to sound an alarm that people who weren’t there can relate to—the idea of something deadly and unprecedented suddenly imposing on your life. Because that’s what’s happening with climate change.”

The title, referencing conditions affecting the occurrence and behaviour of wildfires, orients the reader to the book’s soma, but it’s an early epigraph from 19th-century explorer-naturalist Alexander von Humboldt—first to articulate, among myriad brilliances, the phenomenon of human-induced environmental change—that reveals how that body is built. Humboldt was a quote machine, and Vaillant chose his most definitive: “In this great chain of causes and effects, no single fact can be considered in isolation.”

“All these themes—the histories of the petroleum industry, the automobile, climate science, and wildfire behaviour—are currently in a state of confluence.”

Cause and effect are at the heart of Fire Weather. Humboldt would wince at today’s zero-sum resource policies that fail to consider cumulative or interrelated effects, and this is where Vaillant puts flesh on the bones, exploring the interdependence between fire and human ambition. “I had the bits and pieces for this swirling around in my mind, and one of the reasons it took so long was because I wanted to gather them all under one roof,” he says. “All these themes—the histories of the petroleum industry, the automobile, climate science, and wildfire behaviour—are currently in a state of confluence. And we’re witnessing—living through—this convergence. But where did they all come from?”

Of especial interest are Vaillant’s meditations on fire: its chemical and physical nature, its thereness and not-quite-thereness, its natural rhythms, and how we became who we are in the natural world by assuming the role of fire’s main curator and vector. From our relationship with combustion, Vaillant intuits fire’s roots. “Long before we climbed down from the trees, fire was climbing up into them,” he writes.

Raised against the pastoral and intellectual backdrop of Cambridge, Massachusetts, and literary influences including Melville and Dickinson, Vaillant is adept at using a good story to tell a bigger tale. And there are few bigger in Canada than the controversial development of Alberta’s tarsands, Fort Mac’s raison d’être. As with forestry in The Golden Spruce, tracing the arc of a singular extracted resource lays bare its toxic hubris and environmental fallout without making anyone feel uncomfortable over their participation: it’s just a job, and the offer of employment comes with benefits to sway your decision, not a pocket history. Here, however, the industry’s early development is fascinating, filled with larger-than-life characters and startling facts about oil, energy, and our use—and abuse—of them. The élan with which Vaillant describes hydrocarbons like petcoke, bitumen, and kerosene rivals his astute analogies about fire and strike-it-rich resource rushes. Most revealing—and aggravating—is a thorough excavation of climate science and how long we have known what excess carbon dioxide not only could but would do to Earth’s atmosphere (it’s more than a century).

Which brings us to climate, a mountain Vaillant felt compelled to scale. “It wasn’t in the plan, but I’m always following my own interests and gaps in my own knowledge. You know, ‘How can I talk about this when I don’t know about that,’” he says. “In this case, I was also the beneficiary of a lot of the digging done by others.”

Persuading people to engage over something as paralyzing and polarizing as climate can be difficult. But history shows transformational change accelerates with the right message from the right person at the right time. Youth activism marshalled by Greta Thunberg is an example. Vaillant’s employ of a heartstrings story to paint a picture of what’s at stake should have similar powers. “Most of us don’t react to the numbers and graphs [scientists] use to tell the story,” Vaillant says. “But if you put an experienced firefighter in front of a fire with a firehose, the tool he’s always used to do his job, and hear him describe how pressurized water sprayed into an unburned forest to wet it down was just evaporating, and how he then felt something huge ‘inhale’ and his pants started flapping and the entire forest burst into flame, well, that’s a powerful image. Then he becomes a microcosm for all of us in the face of climate change.”

Fire Weather also consumed seven years because it couldn’t be about a single event. “Things kept happening in ways they never had before,” Vaillant says. “The EF-3 fire tornado in Redding, California, was new on Earth—something never seen before. Something that 200 years of burning fossil fuels has powered up.”

Watching from his writing desk as new disasters exceeded old, one thing appeared constant to Vaillant: no one seemed prepared. “I have this analogy,” he offers, “that every time some unprecedented climate event floors us, the 21st century says, ‘Oh yeah? Think that was something? Here, hold my beer.’”

What he’s describing, a major theme of the book, is the Lucretius Problem—a cognitive defect by which humans assume the worst-case scenario that has happened is the worst-case scenario that can happen. In so doing, we ignore that a worst event has always surpassed a prior worst event. Vaillant writes, “Authorities [around the globe] have found themselves in the same situation—basing their responses on outdated concepts, on what they’ve already seen, instead of what fire weather is capable of now. The data was there, but the interpretation wasn’t, and this—the Lucretius Problem—gave the Fort McMurray Fire an all but unassailable advantage over the people charged with fighting it.”

There are no dangling mysteries here. No Why? No What happened to…? Everything is known; everything is connected. And though its entirety can be plotted by the disquieting equation of What Happened in Fort Mac + Why = Our Inescapable Future, Fire Weather is no jeremiad. As engrossing as any Vaillant work, it’s by turns thought-provoking and lyrical, a paean to literary nonfiction’s ability to convey the breadth of human experience.

Vaillant says that to him his book feels like an extended PSA: everyone knows what is happening, but he has taken the time and effort to show the history and reality of the moment we’re in. “As a citizen, as a participant, as a parent, what I have to offer is the patience to gather information and assemble it in a way that makes you feel you’re there, too. We got a glimpse of how the world ends with Fort McMurray, and that we’re not physically capable of stopping it.”

What happened in Fort Mac was nature’s strongest semaphore to that date of an Earth’s surface so primed and prone to fire weather that, ever since, wildfire records have been set only to be quickly toppled, whether in size, phenomena, particulate matter, towns incinerated, property destroyed, people displaced, or animals killed. As demonstrated by post-2016 wildfire catastrophes, there is no new normal, only an open atmospheric gate through which the climate monsters—portended decades ago but kept from mind by the disinformation campaigns of oil companies—charge headlong into our lives. As Vaillant summarizes, “This is how Earth will remember us: thanks to fire and our appetite for its boundless energy, we have evolved into a geologic event that will be measurable a million years from now.”

In the harsh light of their modern rampages, these beasts can no longer be rationalized away. They’re here to stay—and there’s nowhere to hide.

Grooming by Ashley Gesner for Lizbell Agency. Read more from our Summer 2023 issue.