Nick Milkovich spent almost half his life working with legendary architect Arthur Erickson. In his second year at UBC’s architecture program, he was a student in Erickson’s studio class. By 1968, he was an employee. In the early 1970s, he built study models of Erickson’s Museum of Anthropology. Erickson biographer David Stouck writes that most architecture critics regard the MOA “as Erickson’s masterwork.”

Milkovich, now 85, is more circumspect. “It’s one of Arthur’s better buildings,” he says, in a Mount Pleasant meeting room next to the office where Erickson spent his final working days. One of the six massive concrete beams that define the MOA’s Great Hall is 180 feet long, on just two slender columns. “The structure is insanely irrational.” Milkovich recounts walking through the hall in 2018 with a UBC building project manager, to discuss a seismic upgrade for the engineering marvel. “I think we’re going to have to take it down,” Milkovich told him.

As creation and recreation stories go, the MOA’s is remarkable—both an inspiring and cautionary tale of what’s possible when grand visions preside, or cultures collide, or the earth moves. The museum is being rebuilt on new foundations, inside and out. Important and impertinent questions have been asked. What’s an artifact and what’s a belonging? What’s representation and what is partnership? And what should we do when one of Canada’s important cultural institutions is at risk of collapse?

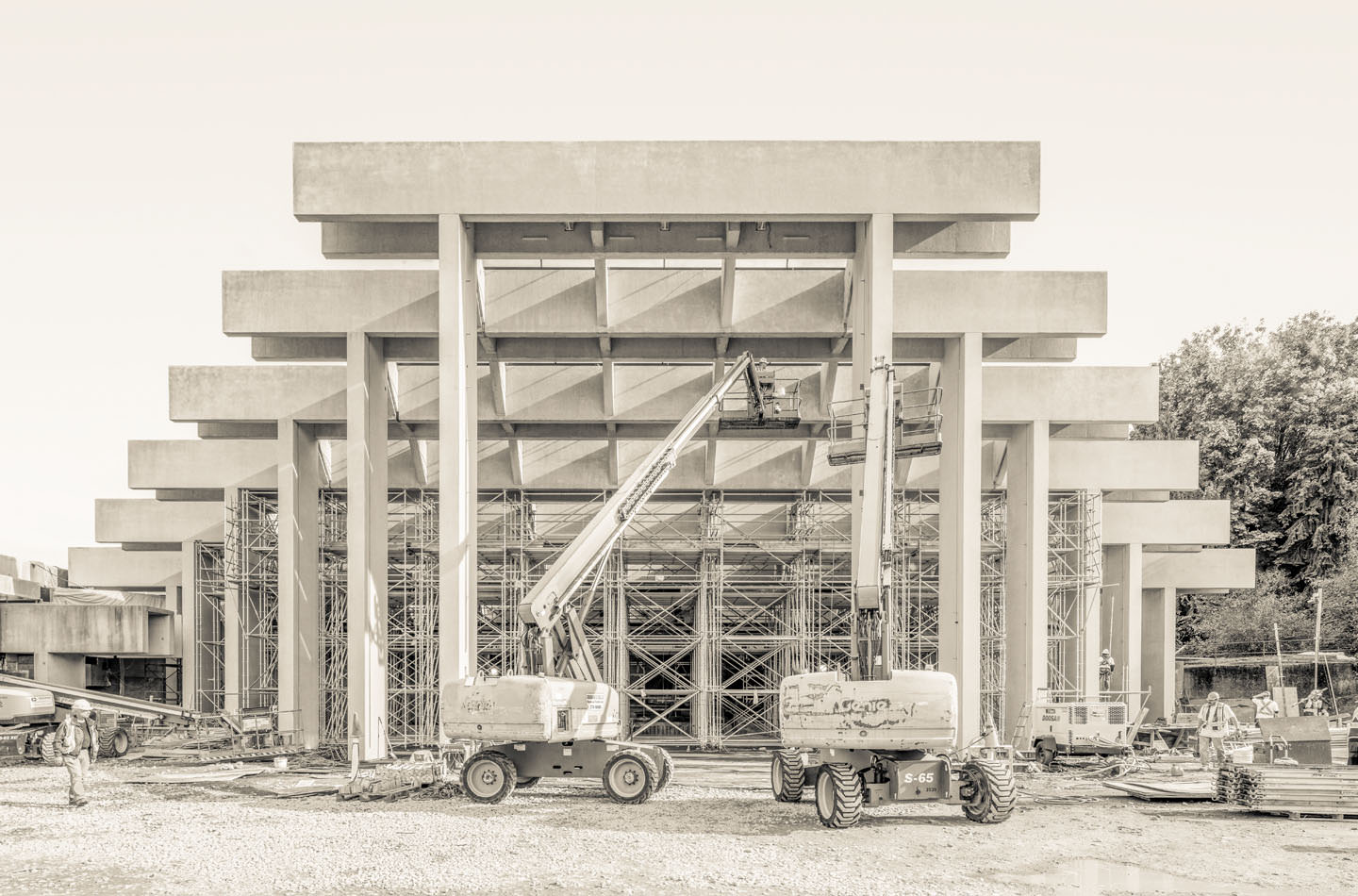

The Museum of Anthropology at UBC being rebuilt to Arthur Erickson’s original vision, after it was demolished for seismic upgrades.

The Great Hall itself did come down, in January 2022. This June, the rebuilt hall will reopen, 75 years after the museum first opened to the public. Twelve hollow concrete columns that should have been solid have now been replaced. They land on composite rubber and steel isolators, unseen beneath the slab of the building’s floor. Milkovich says that in a one-in-2,500-year earthquake, the isolators can deform to 45 degrees, and the modelling suggests the entire building can move 14 inches side to side, at three-second intervals. Every aspect of the Great Hall has to be isolated, from the ground and the adjoining buildings. “Hopefully it will come back to the same spot,” Milkovich says, with a bit of a grin. “It should.”

Of course, a lot depends on the details. Milkovich, whose firm won the Great Hall contract, soon became part of a team that included project architect Anne Gingras, Sydney Opera House and Sagrada Familia consultants Arup, which worked on the hall’s massive glass walls, and Vancouver’s Equilibrium Consulting, whose work on the building’s advanced form of “base isolation” now makes the Great Hall unique in Canada.

“When we leave, it should feel as if we’ve never been there,” Milkovich says.

Susan Rowley is involved in another rebuilding project. The Ottawa-born, Cambridge-trained archeologist and curator, who was appointed director of the MOA in 2021, is working with Northwest Coast Indigenous communities to recast their relationships.

Most museums collect significant fragments of communities that have disappeared. From the Elgin Marbles to the tombs of Egypt, the collecting often involved plunder. On the coast of British Columbia, peoples beset by colonialism were also deprived of their cultural treasures. Some were sold for money often desperately needed. Others were removed as abandoned without a thought to ask. Those cultures were wounded by colonialism, but they were not dead. Yet many treated them as such.

Poles housed in the Great Hall at the Museum of Anthropology at UBC. L–R: MOA Collections nb11.262, by Art Thompson (Nuu-chah-nulth); a50038, by Charlie James (Kwakwaka’wakw); a50035 & a50037, by Mungo Martin (Kwakwaka’wakw); nb11.368, by Joe David (Nuu-chah-nulth).

Indigenous cultural revival has been fraught as well, sometimes by the naivety of wealth and means. Erickson himself described the Indigenous culture he wanted to showcase in the past tense. “At one time, on this coast, there was a noble and great response to this land that has never been equalled.” His museum vision extended to how the objects were curated. “Arthur’s idea,” Stouck writes in 2013’s Arthur Erickson: An Architect’s Life, “was a path that replicated a walk through the forest towards the ocean,” and that rounded naturalistic Salish figures should give way to more symbolic forms of more northerly nations.

That choice privileged the highly stylized poles that were in the Great Hall, particularly the work of Haida and Kwakwaka’wakw nations. Kwakwaka’wakw buildings in particular influenced the museum’s robust structural frame, Milkovich says, and Haida houses and poles soon stood outside, next to a planned reflecting pool designed to echo a North Coast inlet.

Haida art was ascendant in the early 1970s. Haida artist Bill Reid, like Erickson, was a national star. Reid and Erickson were friends. Erickson knew Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau well enough that they swam naked together at his chalet. They were part of a usually Liberal elite—one that included Harry and Audrey Hawthorn, MOA stewards at UBC, where the collection resided in the university library basement. All this drove the creation of the museum building in the early 1970s, essentially by federal government fiat. The budget, according to Milkovich, was $3.1 million.

Reid himself carved one of the museum’s main attractions, The Raven and the First Men. The monumental sculpture sits on one of the Second World War gun emplacements that lie below and around the building. A Haida story of creation, Milkovich says, sits on a symbol of destruction.

However, from the outset, critical voices were not properly seated at the table, particularly Musqueam voices. For them, the cliffside museum site was an important lookout, for fishing conditions and for friendly or occasionally hostile visitors, both before and after European arrivals. “We are on the unceded territory of the Musqueam peoples,” Rowley says, “and yet there was no representation in the Great Hall.”

View of the top of a house frontal pole by George Hunt Sr. (Kwakwaka’wakw), ca. 1914. MOA Collection a50041.

When the museum reopens, two contemporary house boards by prominent Musqueam artist Susan Point will be brought from outside the museum to the Great Hall, along with a 42-foot cedar plank that was once part of a Musqueam big house. As well, the museum’s reflecting pond and grounds are being reimagined in collaboration with the Musqueam.

Other relationships are also being recast. In 2019, at the request of the Haida Repatriation Committee, the museum returned a mortuary pole to Haida Gwaii. “It should never have been taken,” Rowley says.

Yet it was, in 1957 on a Canadian navy ship, under the direction of the Totem Pole Preservation Committee. The committee’s work to preserve poles took place under the auspices of UBC and the BC Provincial Museum. The federal Department of Indian Affairs was consulted, along with Indian agents and band councils, and the project had some support from several forestry companies. Ironically, Bill Reid participated in the committee’s work.

These are the complicated events that the museum must revisit, at an institution where halls echo with the words repatriation and rematriation. Rowley says the museum’s heavy lifting is to establish the provenance of its artifacts. As with the Haida mortuary pole, there are layers of responsibility to sort through.

“Harry Hawthorn and Audrey Hawthorn,” Rowley says, “were really interested in applied anthropology, in anthropology that worked with people to understand where people were at, and to do things with community. No, they didn’t get everything right. Were they making an attempt to do something different? Absolutely. That actually set a trajectory for this museum.”

Yet there were mistakes. “Lots of mistakes.” Rowley reflects on this in the museum’s administrative offices, as new glass is being raised on the Great Hall. “What do we do to move forward, to redress those mistakes?”

As creation and recreation stories go, the MOA’s is remarkable—both an inspiring and cautionary tale of what’s possible when grand visions preside, or cultures collide, or the earth moves.

Transparency is key, she says. So is communication. When the museum asked Indigenous communities what it could do, one result was an internship partnership with six Indigenous institutions. In the credentialed world of academe, too often real expertise is excluded. “How do you measure up if you’re not allowed a chance?”

Jisgang Nika Collison, executive director and curator of the Haida Gwaii Museum, welcomed the return of the mortuary pole—as an act of respect, or yahguudangang—and she values the Haida relationship with the museum. “Early on it was artist-based,” she says. Now it’s broader and more nation-based.

But on the phone as she works her way through Vancouver airport security, on her way to a conference in Niagara Falls, she has sharp words about how museums acquire “artifacts” that were stolen, forcibly taken, or sold under duress. She notes spiritually significant Indigenous artworks are deemed to be ancestors. “Belongings is an important word,” she says. “The removal of belongings and ancestors was part of removing people from the land.”

Collison, who briefly worked with Milkovich on a Haida building project that went unfunded, is frustrated by the absence of resources. The mortuary pole is now in storage, awaiting its return to the village of SGang Gwaay. “People need to consider the cost of post-repatriation care.” She suggests that Canada should look at a 1990 U.S. model, the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, which provides a process and funding for returning artifacts. “We’ve been doing this for 25 years. Where’s the money?”

While Collison values the Haida relationship with MOA, she won’t single it out. Which museums lead in repatriation? Which museums have work to do? “They all do. The Haida lead. We lead.”

Collison also welcomes the role of the Musqueam in remaking the museum. “It’s their land. People should know they are on Musqueam territory.”

The Museum of Anthropology at UBC as seen from the museum grounds before the seismic upgrades project began.

Landscape architect Joe Fry is collaborating with Musqueam to reimagine the work of another Canadian design icon, his late Vancouver colleague Cornelia Hahn Oberlander. “It’s a massive responsibility,” he says.

Fry, whose Hapa Collaborative adjoins Milkovich’s office, worked with Oberlander (then in her 90s) to revitalize her landscape design for Erickson’s downtown Law Courts Complex. “She was revolutionary,” Fry says of Erickson’s frequent creative partner, whose global work includes the native landscaping for the Northwest Territories Legislative Assembly building.

Budget, maintenance, and geotechnical concerns at the cliffside MOA site meant the pool that Erickson and Oberlander envisioned in front of the Great Hall was not permanently filled until 2010, a year after Erickson’s death. Now it’s empty again, and will be redesigned as a river estuary to reflect both its place near the edge of a great river and the word Musqueam itself, which relates to the river and its plant life. “We are trying to correct some of the narratives that have been applied to the site,” he says. “It has been a sore point for Musqueam.”

Three key Musqueam people who work with the museum didn’t reply to interview requests about the museum’s renewal. Time, trust, interest, and the responsibility of speaking for a small community of 1,300 where consensus really matters may be part of that. Their priorities are theirs to set. “The whole of UBC wants to be talking with the Musqueam all day,” Rowley says, “and it’s not feasible.”

The site and landscape improvements, projected to cost about $2 million, involve many players, but Fry says the result is “a design we’re really happy with.” Aquatic plants will help clean the water. Native plants, which are now far more easily obtained, will define different features and locations on the site. He expects the project to be completed this fall.

Fry believes Oberlander would support both the process and the changes. “Rewilding is something that she would want to see.” Oberlander originally included plants important to Indigenous culture at the site. Some argue they disappeared in the hands of UBC’s uniform approach to landscape maintenance. Fry says it is an impediment to what Musqueam partners would like to see at the site, despite UBC’s ability to maintain the culturally unique Nitobe Memorial Garden a few hundred metres away.

The reconciliation movement may have momentum, but practical impediments will persist. Institutions have their habits. Open-hearted dialogue and leadership, though, can overcome quite a bit. When Rowley was appointed, MOA and UBC Musqueam liaison Leona Sparrow said she is “respected for her deeply held relationships and her collaborative style.”

Collison says Indigenous partnership with cultural institutions is critical. What is the place for a colonial museum like the MOA? “If it were built today, it would be a very different project,” she says. Collison adds, though, that Haida elders have said Indigenous cultural treasures can be important ambassadors to the world. “As long as we have a say in how our belongings are looked after.”

Read more from our Summer 2024 issue.