The weight hits me at around 3,700 metres above sea level. The weight of time, heavy on my chest, thinning out the air. My fellow travellers tell me it’s the altitude, but I’m convinced it’s the magnitude of history.

We’re driving through the ancient town of Chinchero, the highest point in Peru’s Sacred Valley of the Incas, which lies between Cusco and Machu Picchu. Patchwork farmland and rolling hillsides pass by in gradients of ochre. Dark grey clouds loom beyond the Andes Mountains in the distance.

The Incan empire, lasting a short but significant century from 1438 until Spanish colonization, was born and based in Cusco—though this fertile land was cultivated by the Chanapata in about 800 BC, long before the Incas. It retains mementoes of Incan engineering: an enduring road network, agricultural terraces, and stone cities. But the allure of the Incas has long culminated at Peru’s top tourist destination: Machu Picchu, the 15th-century, 32,592-hectare stone citadel resting atop a picturesque mountain ridge. That’s where we’re headed.

In tourism terms, Machu Picchu is a titan. The site has seen astronomical increases in visitors since being designated a UNESCO World Heritage site in 1983, from fewer than 100,000 annually in the early ’90s to a peak of 1.6 million just before the pandemic. The citadel is a symbol of both national pride and rampant overtourism. Before stricter rules were imposed, crowds damaged a stone wall and trampled the sacred ground, prompting rumours that the weight of attention was causing the city to sink from erosion.

When we finally reach Poroy train station, I can hardly breathe. I never noticed before, but I tend to hold my breath when I’m deep in thought. It’s not a good habit this high up. The Hiram Bingham train (named for the American explorer who told the world of Machu Picchu) will descend from here to the citadel, which sits at a more comfortable 2,430 metres above sea level.

It’s a languid three-hour journey through sparse farmland into thick, tangled jungle. Waiters float through the luxury compartments, balancing trays of cocktails and coffee—an impressive feat on the rocking train. Laughter and live traditional music pour through from the compartment behind me, yet I can’t stop watching a dead fly rattle on the windowsill. I’m here to write about Machu Picchu, but what more can I say about one of the most visited places on Earth? A place to which Peru hopes to entice yet more visitors.

In 2016, UNESCO threatened to put Machu Picchu on its list of World Heritage sites in danger—a label Peru has avoided by setting timed visits and rules against re-entry. Curiously, the time limit ultimately allows more tourists in, only for shorter windows. This year, the government is raising the cap to 4,500 people a day (5,600 in high season), far above the 2,500 UNESCO originally agreed to.

It’s easy to understand why the country capitalizes on Machu Picchu. Tourism is one of Peru’s largest industries, along with mining and agriculture. And while recovery after COVID has been promising, political protests in January 2023 disrupted many of the country’s travel services and tourist spots, with Machu Picchu closed for nearly a month. Now, more than ever, it’s vital for Peru to bounce back sustainably.

In truth, Machu Picchu is stunning to behold, if you can overlook the crowds and orchestra of camera clicks. The citadel is a maze of stone walls and structures, overlooking a sweeping vista of lush mountains layered in mist. Up close, the stone architecture is astonishing—the Incas didn’t use wheeled vehicles to transport objects. How they managed to build this city is still a mystery.

These scenes of local life, which unfolded naturally and in the periphery of most tourist spots, revealed a more intimate side of Peru than the guided tour.

Back in Canada, I realize that the moments of life and culture I spotted in the shadows of Peru’s most famous attraction struck me more than the summit itself. These scenes of local life, which unfolded naturally and in the periphery of most tourist spots, revealed a more intimate side of Peru than the guided tours. And of course, the geography of the Andean region, with its thin air, naturally lends itself to slow travel.

Because of the altitude, most travel guides recommend spending a day or two in the Sacred Valley to adjust before taking on rigorous activity, though I would stretch it to three or four days, moving leisurely and noticing more, such as the female shepherds who dot the vast hillsides, wearing felt hats called monteras. The roasted whole guinea pigs on skewers, a traditional delicacy, which flag streetside food stalls. The inconspicuous plastic bags tied around sticks outside certain establishments, indicating the fermented corn beverage chicha is available inside. And the way the Andes Mountains loom protectively over the valley, cutting a sharp, jagged silhouette across the horizon.

The local Quechua, descendants of the Incas, breathe easy up here. But nearly everywhere I go, I’m offered a coca tea, a herbal remedy for altitude sickness. I take small sips of the gentle-tasting drink at the textile market in Chinchero as I watch a demonstration of hand-weaving, spinning, and natural dyeing methods: turning dull wool into a brilliant red by crushing a cochineal insect or an earthy green using ch’illca leaves.

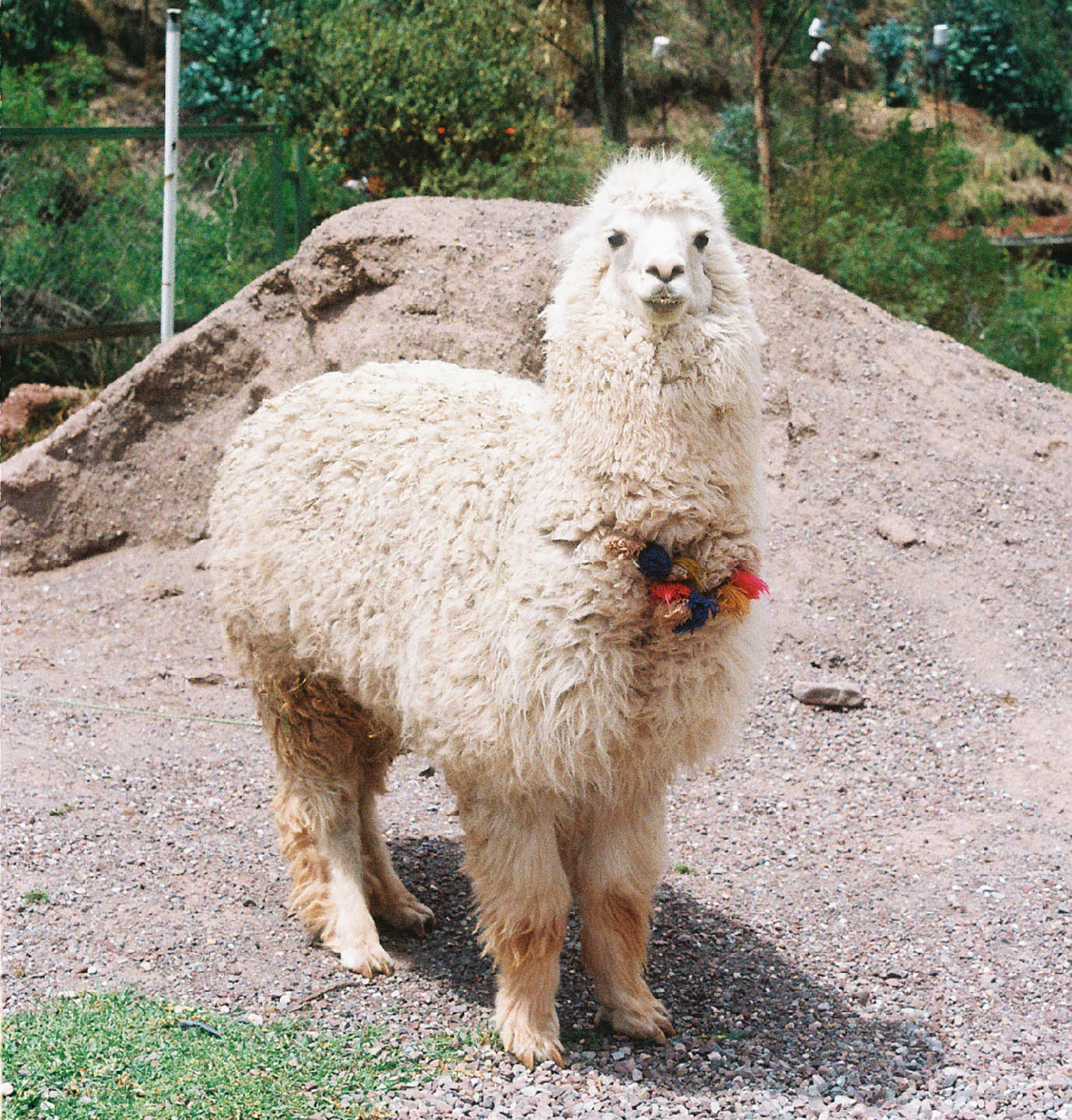

Here, Incan weaving traditions are retained by the local women, who in turn show these methods to tourists and sell soft-as-a-cloud vicuña blankets and alpaca shawls to support themselves. In the corner of the room, amidst the vibrant wool and backstrap looms, squeaking guinea pigs clamber over each other against the wires of a cage. Behind me, a child shyly peers behind a tapestry. And when our host demonstrates how local Quechuan women carry infants in blankets wrapped around their backs, a beaming baby is produced.

Later, while wandering across the property at Unu, a restaurant in a lone colonial hacienda in a vast panorama of farmland, I come across two shepherds: a grandmother and granddaughter. A new lamb has just been born, the shepherds point out. Not five minutes ago, it seems. The bleating lamb is still covered in placenta, and the mother energetically licks it clean while watching us out of the corner of her eye.

The grandmother, Emelia, wants to know my name. “Safe travels,” she says, giving me a hug. Meanwhile, Maribel, her teenage granddaughter, runs around trying to catch a lamb for a photo. The interaction, though fleeting, feels sincere, the type of slice-of-life moment that only comes by being in the right place at the right time.

Machu Picchu, with its one-way paths and bottlenecks of selfie-taking tourists, leaves little room for such moments. Standing atop the ancient world, I have only a few moments to savour the weight of history before being hurried along. But if it’s history I want, there are lesser-known Incan ruins to turn to, such as Moray, where agricultural terraces divulge the secrets of Incan farming experiments.

For better or for worse, Peru must contend with the gargantuan reputation of its most-visited site. But the Sacred Valley, too often seen only in passing between Cusco and Machu Picchu, can reveal so much more about the country and its people—if you take the time to notice.

Read more from our Spring 2024 issue.