Tantoo Cardinal was living just two blocks from the evacuation line during January’s Los Angeles wildfires. That was, she tells me, “the last straw.”

She relocated temporarily to Alberta as the city burned, but the situation only cemented an earlier decision to make a move back to Canada following the 2024 U.S. presidential election. “It was just feeling a little shaky,” she says, as we catch up by phone from her home in Edmonton. “I was feeling it right away.”

Of Cree and Métis descent, Cardinal—arguably Canada’s most significant Indigenous actor—says she has never been particularly tied to one side of the border or the other, moving back and forth too many times to mention since first heading to L.A. following her breakthrough role in Anne Wheeler’s Canadian drama Loyalties in 1986.

Dorothy Grant cape and hat; blouse Cardinal’s own.

Nevertheless, she says, Indigenous voices are more prominent here. “Canada does much better than the U.S., because we’re in dialogue, and you come to Canada and right away I hear our stories. I hear what’s going on in our communities,” she explains. “But over there, no, you really have to dig around to find any stories of legitimacy about who we are and what we’re doing and what’s really going on or what our perspective is on something that’s happening.”

For now, at least, she says she is happy to be back. “My family is here, and some old tried-and-true friends.” She’s looking ahead and “starting on a new page.”

Looking forward to new possibilities is something Cardinal has mentioned to me before, a way of approaching life that keeps the screen veteran—who turned 75 in July—inspiringly youthful.

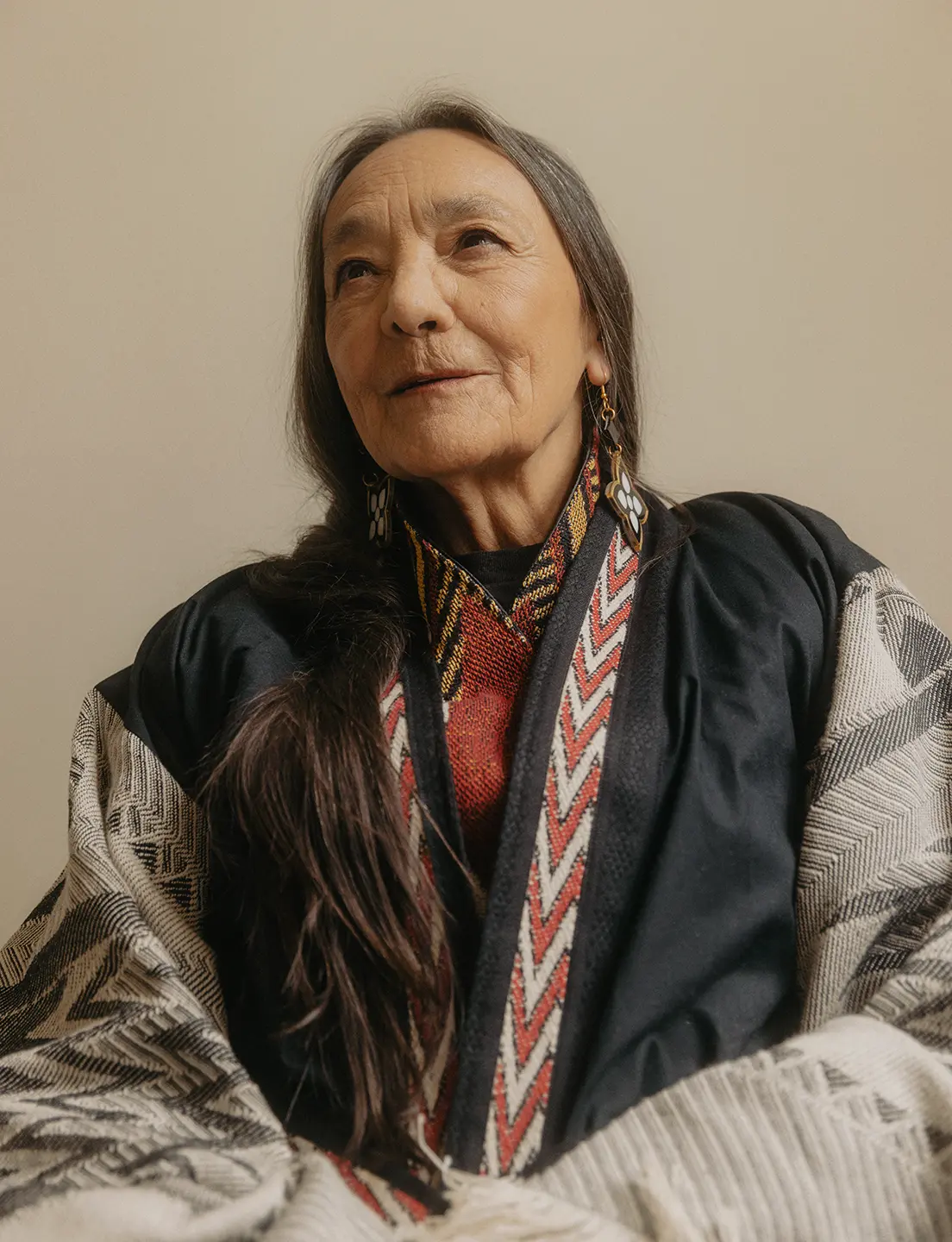

Cardinal wears an Aleen Sparrow woven jacket; her own denim, shoes, and earrings.

When we first meet, it’s December 2024, just a month after that fateful U.S. election, and Cardinal is attending the Whistler Film Festival as a jury member. Skiers shred their way down the slopes just outside the window of a warm Fairmont Chateau Whistler suite.

It’s been a long festival for Cardinal already, with a full schedule, but she has a relaxed air about her and walks confidently to greet me. She’s wearing a black leather jacket and a skirt that nearly touches the ground, but it’s her earrings that catch the eye: bright turquoise feathers that pop against her dark hair.

“I’m kind of at a new beginning,” she says. There’s hope and excitement behind the words, but also a hint of curiosity, as if she’s trying to complete the thought: the beginning of what?

“Being present in the moment of acquiescence, I guess, is as close as we’re getting to equity, really.”

After half a century onscreen in projects as diverse as Chris Eyre’s 1998 movie Smoke Signals and Kevin Costner’s Dances With Wolves (1990), and more recently, Martin Scorsese’s 2023 Oscar-nominated Killers of the Flower Moon and the 2024 Marvel superhero television series Echo, Cardinal’s list of credits is impressive.

Her accomplishments are well documented. She is a Member of the Order of Canada, has received recognition from both the Academy of Canadian Cinema & Television and the Gemini Awards (as was), the Screen Actors Guild, and many more. She also has a star on Canada’s Walk of Fame.

She takes the accolades with a grain of salt, chuckling when I bring up her 2025 Equity in Entertainment Award win at The Hollywood Reporter’s Women in Entertainment Canada summit and awards gala in Toronto. “You know, equity—we’re not there yet. We’re not anywhere near that, but I guess we’re closer than we’ve been,” she says. “Being present in the moment of acquiescence, I guess, is as close as we’re getting to equity, really.”

Aleen Sparrow woven jacket and vest; T-shirt and earrings Cardinal’s own.

This frankness is a constant with Cardinal, who has spent her career challenging norms by speaking her mind. The incredible weight on her shoulders is not lost on her as she considers her words carefully. A deep sense of responsibility, she says, has shaped so many of her acting choices, and she’s reaching a point of transition. “My mania, my raison d’être, was to expose us to the public, you know, to get us out into the mainstream. To have our voices heard, to see our images.”

She’s had more than a few successes. “There’s been an enormous change in my lifetime,” she says. “And people all across the board have to be credited for that, because we inspired each other to keep breathing and to get fresh air and to deny those assumptions and those decisions that were being made about who we are.”

Born in Alberta, she was raised in the small northern hamlet of Anzac by her grandmother, whose friends would visit and tell stories in different languages. Cardinal always listened. “I was always drawn to that and loved the people in our community that would play instruments and sing songs and dance, and the champion jiggers would just always draw a crowd,” she says.

“And of course, the storytellers.” She soon began telling stories herself on stage, first in a Christmas concert. “My sister-aunt was telling me, ‘You’re the only one we could hear.’ Everybody was too shy,” she explains. “I wanted to be heard.”

In junior high, she had support from a teacher who could see the acting spark and helped her get to Edmonton. The school in Anzac only went up to Grade 9, and the city offered high school and more acting opportunities. It also conferred outsider status on the young Cardinal, isolated and far from home and subjected to racist abuse.

It’s been a long battle to distance herself from the stereotype of the “dumb Indian,” even to this day. “It’s really obstructive, and I would say I’m just now being able to wrestle it out of the way,” she says. “Because those are formative years. That’s a really big battle to get rid of, especially if you hear it in your home and in your community, and your own people are saying that to each other.”

Aleen Sparrow woven jacket and vest; T-shirt and earrings Cardinal’s own.

There’s still far to go, she notes, but she is proud of what she’s accomplished and wants the next generation to understand the struggle that went into current realities within the entertainment industry. She tried to impart this to a group of early-career filmmakers from across Canada at the festival in Whistler. “I want them to know that a lot of work has been done for them to be in the position that they’re in,” she says. Opportunities don’t come out of nowhere, and they shouldn’t be taken for granted. “There’s such a change to that tapestry that you’re standing on. It’s been well fought. And work has been done before you got here.”

She’s still hard at work off camera too, pushing to create more opportunities for Indigenous kids in Canada who may get something out of acting, as did she growing up.

“I needed to hear our stories, and I needed the world to see that we had stories, that we are way more, and we are way else from what they’re being fed about who we are or who we were.”

In 2021, she launched Tap Root Actors Academy in the Kikino Métis Settlement in Alberta, just a couple of hours northeast of her new home in Edmonton. Tap Root is an acting and filmmaking school for Indigenous youth in the area. The whole endeavour is designed to strengthen community through artistic expression and Indigenous storytelling while also fostering tangible, transferable skills in the next generation.

“What we’re discovering is it’s a place of strength and resilience and hope for young people of the community,” she says, describing the enthusiasm the students have for learning, including spearheading their own forays into podcasting and animation. Beyond learning technical skills, the sense of community is what Cardinal stresses, including reconnecting family members in one instance. “I think that the parents are really hopeful because their kids are in a positive place.”

She credits her own need to heal for launching the school. “And that I needed to hear our stories, and I needed the world to see that we had stories, that we are way more, and we are way else from what they’re being fed about who we are or who we were.”

There is, of course, power in stories—and who tells them. Cardinal describes depictions of Indigenous peoples generally as a kind of coverup, to sweep away the sins of colonialism. It’s part of what drove her to act in the first place, and to carve out a place for herself in an industry that was outright hostile to her presence at times.

“It was just to prove them wrong,” she says, only half-joking. “I remember the thought that I had when I first started accepting work in this industry, and why I went into it is I wanted to expose the lies. And I guess that’s still a part of me.

“I always think the truth is stronger than some imaginary thing based on no information, or bad information.”

It’s not just that authentic stories need to be heard, but also that the lies and propaganda need to be countered. “Some people say, ‘Well, residential schools were well-intentioned,’” she offers as an example. “The way I look at it is, genocide hadn’t been complete. So take the babies, kill the parents, kill the grandparents, and then kill whatever it is that they had placed in these children: love. And that’s not well-intentioned.”

Cardinal’s career is marked by great acting, of course, but also by carefully chosen projects that speak to the Indigenous experience in Canada and the United States, whether that’s the celebratory coming-of-age seen in Smoke Signals and The Grizzlies, the critical reassessment of American and Canadian colonialism in Dances With Wolves and Black Robe, or the unvarnished confrontation with violence against Indigenous women in On the Farm and Killers of the Flower Moon.

“I didn’t fight with anybody,” she says, when I ask about the filmmakers she’s worked with and whether they welcomed her input. “I could only work with the ones that were receptive, so I worked with the ones that were receptive.”

On the set of Dances With Wolves, for example, she pushed for the use of the Indigenous Lakota language. Classic westerns often made up “Indian” languages or had Native American characters speak in accented English. She credits the collaborative spirit of the film’s casting director. “Elisabeth Leustig, bless her soul, was completely open, and it was because of her that those changes could be made.”

Ay Lelum cape; blouse Cardinal’s own.

While screen depictions of Indigenous peoples have come a long way in the 35 years since, those collaborations represent major steps forward. Martin Scorsese and the producers of Killers of the Flower Moon worked with members of the Osage Nation to include their feedback in creative decisions. That involved speaking with the families of victims and working with Osage language consultants, as well as casting Osage members. It’s easy to connect the dots between what Cardinal was pushing in 1990 and what is seen by many as respectful due diligence today.

Asked about what’s coming up, she speaks fondly of a recent project she wrapped—a new adaptation of George Bernard Shaw’s 1905 play Major Barbara—shot in Vermont by her friend and director Jay Craven, who she worked with on 1993’s Where the Rivers Flow North. She says she is ready for more comedy. “I’d love to be able to just kind of branch out.”

And then there are her forays into animation, with voice work in several projects, including the upcoming Wildwood, from Laika Studios, and the short film Inkwo for When the Starving Return. “It’s really exciting,” she says of Inkwo. “It kind of enfolded me into this world of Indigenous animation.”

After the film festival in Whistler, she was headed to Iceland to film the new season of Netflix’s live action version of Avatar: The Last Airbender. In it, Cardinal plays Hama, a former prisoner of the evil Fire Nation on a generations-long quest for vengeance. She returned to Vancouver for another round of filming in the summer. “It’s a great opportunity for me, and it’s well written,” she says.

She’s ready for another gear change—that transition she mentioned earlier. “I find that I have been more of an activist than an actor,” she elaborates.

“I’m at a place where I want to kick back and maybe just do some acting and get into a world that’s not defined by my culture or defined by my history or defined by any of that.

“I want to see if there are any filmmakers out there who would consider me just a human being—without some big explanation of why the Indian is in the room.”

Read more from our Autumn 2025 issue. Prop stylist: Rader Turner. Hair and makeup: Win Liu with Lizbell Agency. Digitech: Sean Best. Photographer’s assistant: Marlin Olynyk. Styling assistant: Rosemary Fisher-Lang. Production assistant: Josie Breuls. Post-production: Marius Burlan.