“Like this.”

Cheng Fanfan is teaching me how to wrap a dumpling—leaning over my shoulder in an emerald-green Tang-style shirt embroidered with peonies. With precise pressure, she pushes the filling—white cabbage, sweet corn, and mushrooms—into the dough with her thumb, crimping it with her fingers into a neat pleated curve. She makes it look easy, but I find otherwise: my dumpling emerges bulbous and stretched, with oversized doughy pleats.

It’s a matter of practice. Cheng learned how to wrap a dumpling—a jiaozi, to be precise—on her grandmother’s knee in the small village of Mulei in Xinjiang, China. Mulei sits on the edge of the Gurbantünggüt Desert, near where a northern branch of the old Silk Road slips between the glacier-capped Tianshan mountains. She grew up eating everything from Chinese jiaozi to Kazakh stuffed naan and local steamed rice cakes studded with raisins and dates.

Now we are sitting in Little Karp, her restaurant in Richmond, illuminated by persimmon-shaped lanterns and hanging lights in the shape of fish traps. Cheng serves a modern, international brunch and dinner menu focused on local seafood, but dumplings are always somewhere on the table—sometimes traditional, sometimes more inventive recipes such as duck-stuffed tortellini. Chinese people, she tells me, traditionally see dumplings as symbols of good fortune because their shape is reminiscent of ancient imperial gold ingots, but the positive associations are deeper, and more emotionally rooted.

“When you gather together, you eat dumplings. When you have a holiday, you eat dumplings. On the new year, you eat dumplings. On the winter solstice, you eat dumplings,” she says. “It’s not just that dumplings symbolize wealth or prosperity. It’s that you know that when you are eating dumplings, something good has happened.”

Her childhood at the axis of the Silk Road made Cheng a keen observer of dumplings. The simple concept of a meat or vegetable filling stuffed inside a starchy packet and steamed or boiled can be found almost everywhere in the world. But there’s a special relationship between dumplings and the Silk Road: a cultural interchange between East and West that reaches all the way from Italy up through the steppes of central Asia, the fertile basins of China, and out to the islands of Japan in the Pacific. Ideas travel back and forth. Divisions between cultures are muddled inside soft pockets of dough and meat—from ravioli to wonton.

To wrap up all of these foods into a single word would be, in the East Asian culinary imagination, absurd.

It’s a pattern duplicated in miniature in Richmond, an exuberantly diverse city with at least as many varieties of dumpling as immigrant cultures. Cheng’s restaurant is one of 17 that make up the Richmond Dumpling Trail, a project devised by the city to attract diners to the vast diversity of Asian dumplings found there.

Given their deep importance to East Asian culture and to chefs such as Cheng, there’s one fact that is a little surprising: there is no word for dumpling in Chinese—nor in Japanese, nor Korean. The concept of dumplings is alien to East Asian culture, a foreign framework placed on a cornucopia of foods to aid in western understanding. It’s not, of course, that dumplings aren’t important enough to Chinese people to deserve their own word; it’s that they are too important. A baozi is a baozi and needs its very own category. A jiaozi is a jiaozi. A tangyuan is a tangyuan. To wrap up all of these foods into a single word would be, in the East Asian culinary imagination, absurd.

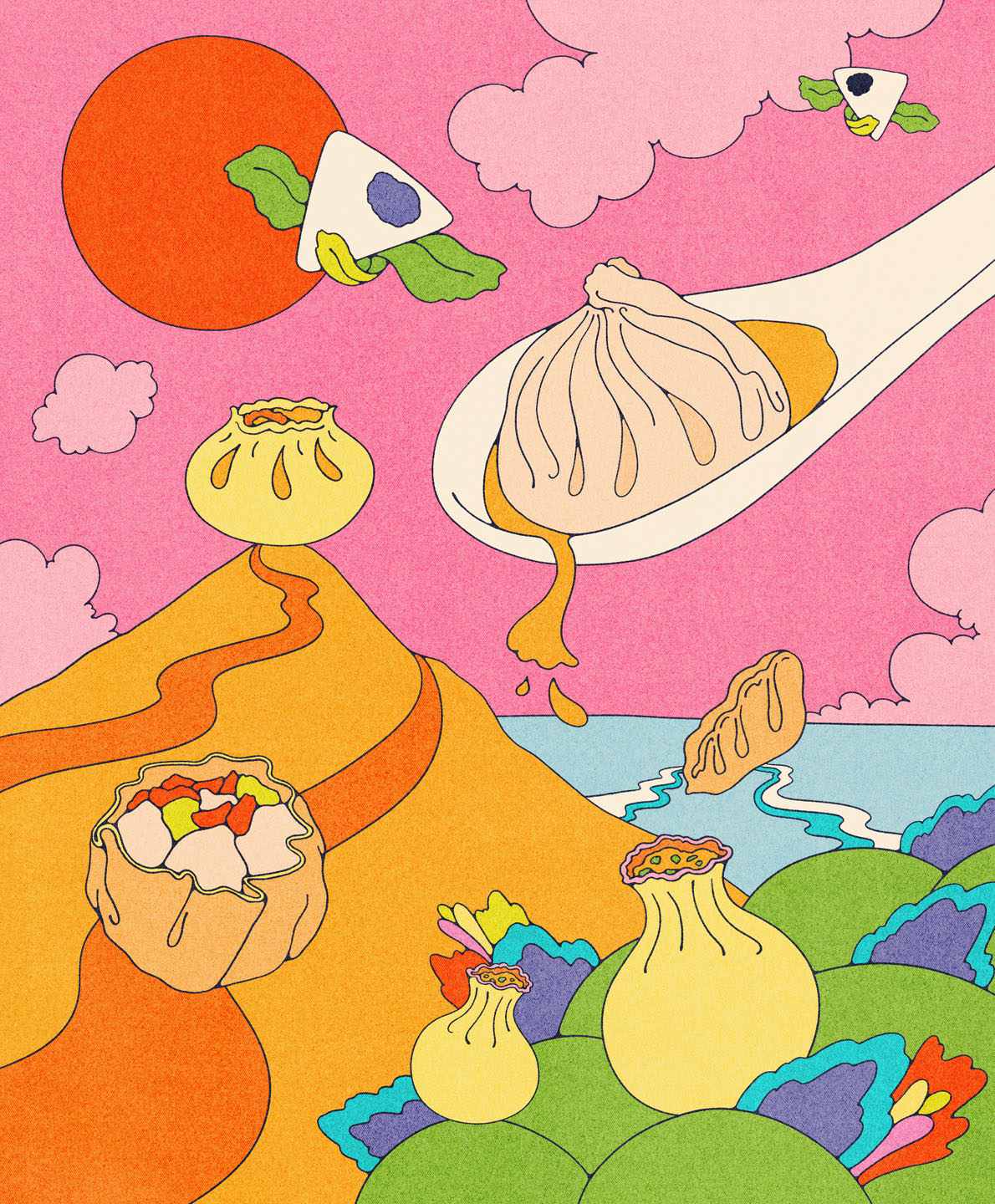

But call them what you will, there are dozens of varieties of dumpling cooked across East Asia: plump Chinese baozi and moon-shaped jiaozi, greasy fried shengjianbao, red-bean stuffed tangyuan and sticky-sweet Japanese dango, rich Tibetan momo stuffed with yak, chewy Vietnamese bánh bột lọc, delicate xiaolongbao brimming with hot soup, open-topped siu mai served with afternoon tea, and pyramidal zongzi wrapped in neat bamboo-leaf packets. And nearly every variety can be found somewhere in Richmond.

Just a short walk from Little Karp, I discover an embodiment of the boundary-crossing power of dumplings in the back kitchen at Yuu Japanese Tapas, a bustling and Instagram-friendly diner that has served ramen in Richmond since 2010. Accompanied by the clatter and clang of ramen bowls and stock pots, Sam Chan shapes Japanese gyoza with machine-like beauty and precision, each with the exact same number of folds as the last, wielding a short wooden paddle to paint the right amount of pork filling into each dumpling. Chan was born in Hong Kong but spent 20 years cooking Cantonese food in Tokyo. Now he makes Japanese food in Vancouver, working in the restaurant of his Hong-Kong-born niece and her Japanese husband.

“I went there to teach Japanese people,” he says, his face crinkling with a smile reminiscent of the god of good fortune perched behind him on a stainless steel shelf. “But when you see something good, you have to learn a little, too.”

His niece and Yuu’s owner, Julia Kubotani, explains that while Japanese gyoza are shaped like Chinese jiaozi (they also share a linguistic root), they taste different and serve a different culinary role. Gyoza are smaller, with a thinner skin, and are pan fried for a crispy crust. At Yuu, the secret ingredient is a splash of ramen broth added to the filling for juiciness. Instead of a meal in themselves, gyoza are a satisfying, texturally contrasting side dish to comfort food, like ramen.

“In North America, if you have a sandwich, you have to have a bowl of soup on the side,” Kubotani explains. “It’s that kind of feeling. If you just buy a sandwich, it’s dry and missing something. It’s just like if you have just a bowl of ramen, it’s missing something too. The gyoza give it something crispy and juicy.”

There is something inescapably homey about dumplings—a food of simplicity, convenience, and family cooking. But they can also reach the height of elegance. At Empire Seafood Restaurant in the heart of Richmond, head chef Raymond Ng makes palm-sized works of art by hand, served in bamboo steamer baskets—towering comet-shaped taro dumplings stuffed with duck, delicately translucent shrimp-filled har gow, and savoury mushrooms wrapped in pillowy wheat-starch blankets. All of these dishes and more—some of which stretch or exceed the definition of the word dumpling—make up dim sum, a relaxed Cantonese midday meal accompanied by tea and conversation.

I ask Ng how he learned to make dim sum, and he answers with one word: “Poverty.” He started in a Hong Kong kitchen when he was 11, working his way up through the skills of steaming, mixing, and finally the careful work of wrapping the dumplings. He arrived in Canada in 1974, just as dim sum was expanding beyond Chinatown. Inside the maze-like Empire kitchen, he stands at the rice-flour-dusted bench and coaxes circles of mochi-like dough around pork and radish filling, achieving the right tension so the dumpling won’t break in the steamer. Now, after 62 years of making dumplings, he says they feel like a hobby, a passion, rather than a job.

How long does it take a chef to master the art of dim sum? A long time, he insists. Maybe 15 years of work, to meet Ng’s exacting standards. Beside him at the bench, a young apprentice slowly fills a sheet tray with football-shaped pork dumplings for the deep fryer—a technique passed down from hand to hand.

Nearly two decades ago, I stopped at a dumpling shop in the ethnically Tibetan high country of China’s Sichuan province. Nestled at the edge of a village, the shop’s open courtyard looked up at a grassy hill where shaggy yak grazed in the sunshine—perhaps relatives of those whose meat filled the dumplings. An entire family was at work preparing jiaozi for lunch: rolling dough, stirring the filling, tending the pot of boiling water. I was transfixed by the elderly matriarch, who formed the dumplings while chatting away in lilting Tibetan. As she talked, she grasped a circle of dough in each hand, pushed the filling into the centre with her thumbs, and clasped both hands tightly into fists. Then she cast the two dumplings out onto a floured tray as if throwing dice, each emerging perfectly formed.

Remembering this moment, I ask Cheng about the physical practice of making dumplings, passed on from generation to generation, and how it shapes how she feels about the food.

“Dumplings aren’t a food you can make on your own. There has to be someone wrapping them, someone making the dough, someone cooking them. It takes teamwork. On your own, you can’t make good dumplings,” she says. “And if you’re making dumplings together, you’re going to chat. You’re going to talk about what’s going on. You can relax.

“It’s a kind of tuanyuan,” she says in Mandarin—a kind of gathering together into a whole. It isn’t until later, when I’m trying to translate the word, that I realize tuan, the collective whole, is also the name for a kind of dumpling.

Read more from our Summer 2025 issue.