Monica experiences excruciating pain when she and her husband attempt sex. She has become avoidant of all romantic interactions for fear they may lead to sexual activity. She no longer has bubble baths, avoids her annual visit to the gynaecologist, and has lost all sense of being a woman. She has a condition afflicting many of her female friends and acquaintances, but she does not know it. Because of her embarrassment, she suffers in silence.

Provoked vestibulodynia (PVD) is a chronic pain condition localized to the entrance of the vagina. Women will describe the symptoms as feeling as if someone is cutting, burning or tearing the opening of the vagina. It affects about 12 to 15 per cent of women; however, most family physicians and many gynaecologists do not understand it and therefore do not make an accurate diagnosis. As a result, research indicates that most women experience the symptoms for over three years and see a number of different health care providers before receiving an accurate diagnosis and beginning treatment. In the meantime, symptoms worsen, other components of the sexual response, such as desire and arousal, become impaired, and there is a significant toll taken on the woman’s self-esteem, her quality of life, and her relationship. The provoked nature of PVD, as its name implies, suggests that this pain is experienced only when the opening of the vagina, or introitus, is touched, as occurs with many forms of sexual activity, tampon use, cleaning or during a gynaecologic examination. Because many physicians do not understand how to make an accurate diagnosis of PVD, many erroneously assume it is a yeast infection or a urinary tract infection—two different conditions often provoking genital pain in women. However, the anti-yeast, anti-fungal or antibiotic treatments given for these conditions do not help and, in fact, often worsen the pain in women with PVD. She may return to her doctor’s office a few months later complaining that the pain has not lifted or even worsened. What becomes very frustrating for many women is that there is often no visible sign of redness or any other anomaly, leading some insensitive physicians to tell the woman that the pain “must be psychological” (read: made up) since they cannot see any sign of injury. Being told that the pain is “in your head” only worsens the woman’s distress and sense of hopelessness, and may further negatively impact the pain.

Until recently, there were no North American treatment centres offering a multidisciplinary and integrated treatment program all in one centre.

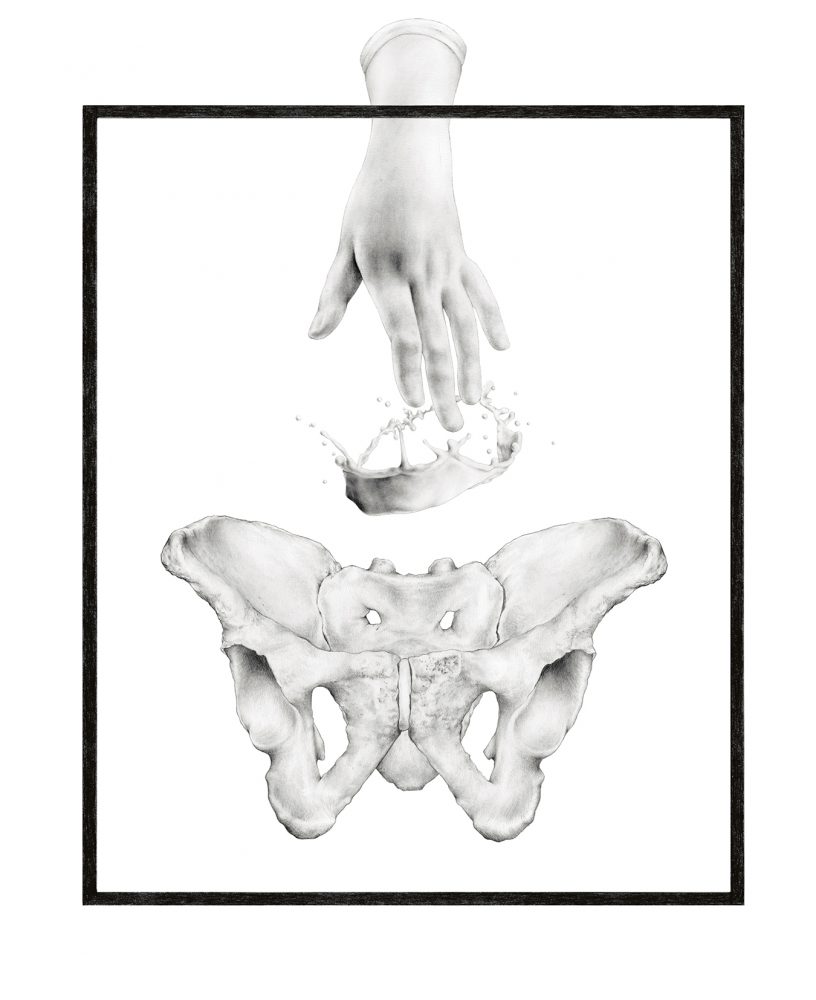

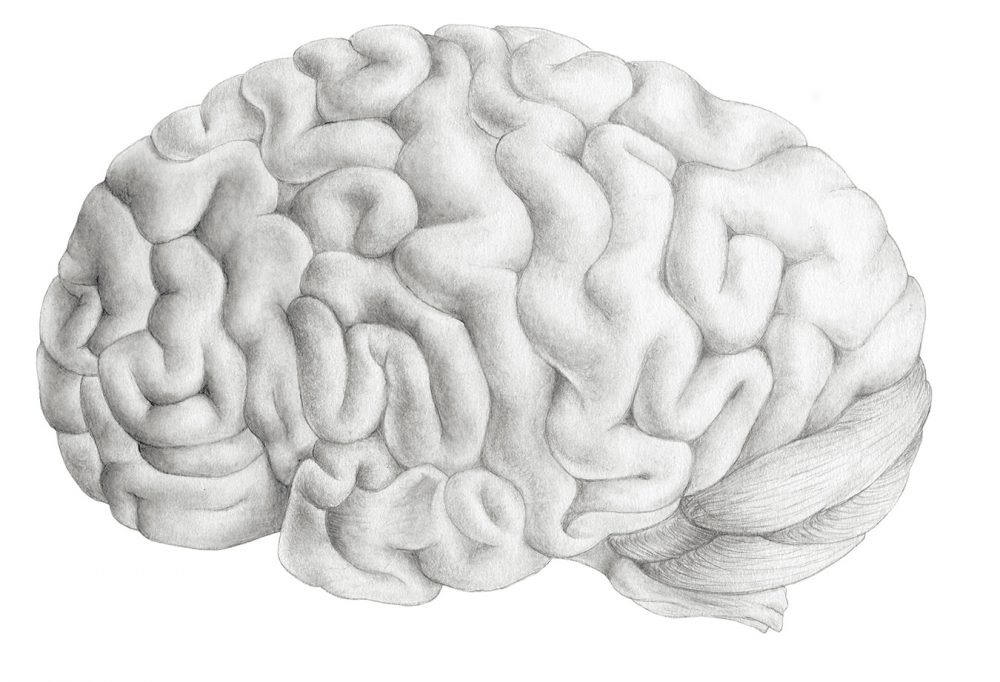

PVD is what is known as a neuropathic pain, meaning that it relates to dysfunction in the pain centres located within the brain leading to “central sensitization” or a hypersensitivity to touch and pain in the body due to a proliferation of pain receptors in the vestibule. It is not an infection of the genitals. It is not a sign of cancer. It is not a sexually transmitted infection. And it is not lack of lubrication, as experienced by many postmenopausal women. Thus, the recommendation by some physicians to “just use a lubricant” does not solve the pain dilemma and can promote sexual activity that continues to be very painful.

Because PVD is due to a dysfunction in the brain’s pain system, treatments may target the brain in order to relieve women’s pain. Antidepressant medications and anti-seizure drugs, both of which reduce the amount of neural output, are often considered. However, only about 50 per cent of women respond positively to these medications, and the drowsy side-effects make them intolerable for many women. Pelvic floor physiotherapy can be effective for teaching women to have better control over their pelvic floor muscles and to reduce the negative impact of chronically tense pelvic muscles on genital pain. One of the limitations, however, is that there are very few physiotherapists specialized in pelvic floor dysfunction, making waiting lists very long, and the fee-for-service structure impossible for some. Psychological techniques in pain management are also an adjunct in women’s care and show good outcomes in many women in terms of better pain control, reduced distress, and improved sexual functioning. Here, too, however, patients are required to pay for appointments on their own, and not everyone has the extended benefits coverage that makes this a viable option. For some women who report minimal benefits from prior treatments, surgery becomes the only option for relief. Vestibulectomy involves excision (removal) of a few millimeters of tissue around the vulvar vestibule, and at least 50 per cent of women who have the procedure will experience pain relief.

Most experts in PVD will agree that an optimal treatment approach involves an integration of these methods. Thus, topical or oral medications might be prescribed and managed by a gynaecologist; a psychologist might teach pain management, relaxation, and distress reduction techniques; and, a pelvic floor physiotherapist, using pelvic floor biofeedback, would teach the woman to gain better control over her hypertonic pelvic floor. Although this is an ideal treatment package, the onus is on the woman to seek these services independently and to pay for such treatments. Moreover, even among the minority of women who mobilize these different providers, it is exceedingly difficult for the different providers to communicate such that their care is optimized for the individual woman. Until recently, there were no North American treatment centres offering a multidisciplinary and integrated treatment program all in one centre.

Women who have completed the Multidisiciplinary Vulvodynia Program to date have expressed gratitude for its existence and report significantly reduced distress.

Then in September 2008, a new Multidisiciplinary Vulvodynia Program (MVP) at Vancouver General Hospital was established with generous start-up funds from Vancouver philanthropist Mrs. Leslie Diamond. Women take part in a four-month intensive program involving individual and group sessions with a gynaecologist, a pelvic floor physiotherapist and a registered psychologist conducting group psychoeducational sessions. Women who have completed the program to date have expressed gratitude for its existence and report significantly reduced distress. The reality, however, is that this is a one-day program that could easily transition into a full-time clinic given the long waiting list of women with chronic vulvar complaints. Funding is a significant limitation because the funds were not designed to sustain a program, but rather to design and launch one. Unfortunately, there are currently no provincial funds for sustainability, leaving the ongoing operation of the program up to fundraising efforts and patient donations. In the meantime, women on waiting list are anxiously trying to get into the MVP while it is still operating.

For Monica, an optimal treatment regimen would involve, firstly, establishing a relationship with a gynaecologist knowledgeable in vulvovaginal pain conditions. A gynaecologic examination in which the physician uses a cotton swab to gently touch the opening of the vagina is used to confirm the diagnosis. Depending on her particular medical history, drug sensitivities and other associated mood symptoms, the physician might begin Monica on a medication for some immediate pain relief. She would then be encouraged to seek a pelvic floor physiotherapist who would begin her on some specific exercises to develop skills for building awareness over her tight pelvic floor. Ideally, she might see this individual for 10 sessions. Because of the significant toll taken on her self-esteem, mood and relationship, Monica would also see a registered psychologist with expertise in sexual health and pelvic pain disorders. The psychologist would work with Monica to address pain behaviours that might be contributing to the pain, teaching her stress-reduction techniques, encouraging her to challenge and replace problematic (irrational) thoughts leading to distress, and working with her and her husband to develop a wider and healthier sexual repertoire. This optimal treatment approach would position Monica best for improved pain and distress so that she can enjoy the qualities of life she once did.