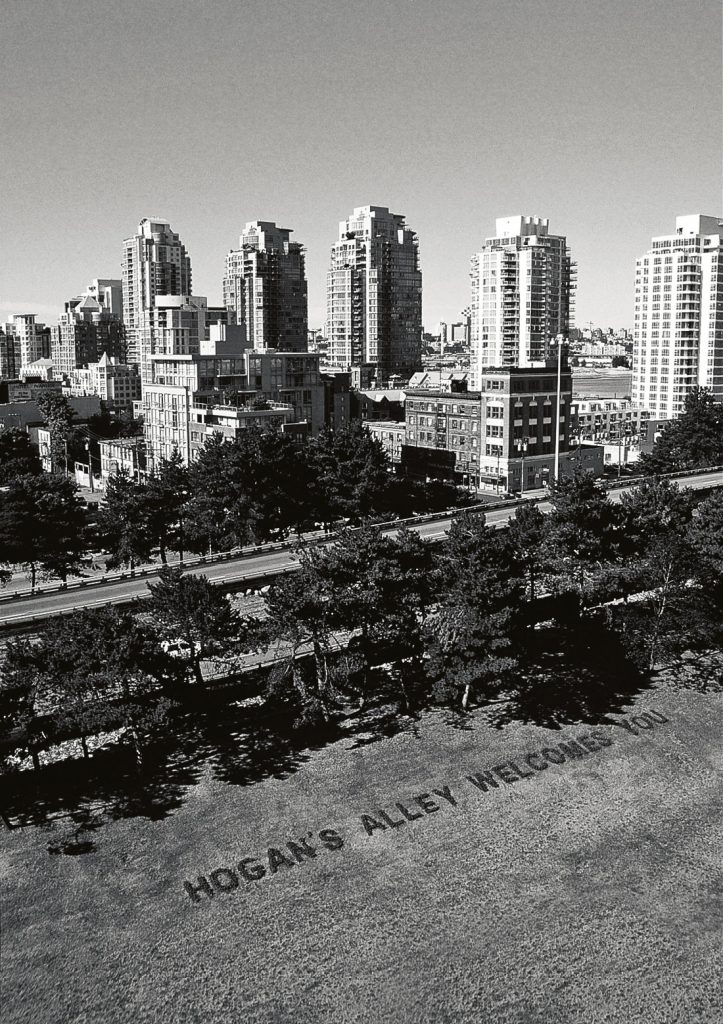

Tucked away beneath a busy Main Street overpass lies an often forgotten part of Vancouver’s history. What is now the Prior Street off-ramp of the Georgia Viaduct was once Hogan’s Alley—a predominantly black neighbourhood in Vancouver’s East End that thrived from the 1930s to the 1960s. The small area was home to the first black church in the East End—a church that Jimi Hendrix’s grandparents would frequent on Sundays. More importantly, it was there that the black community banded together, put down roots and found a space all their own.

“The proximity to the rail stations made Hogan’s Alley a natural place for many black folk to settle,” says James Johnstone, a resident of the East End and house historian extensively researching the neighbourhood. Johnstone is trying to rebuild an accurate map of what it looked like in its prime, before it was taken over by the viaduct. “Back then, baggage porter, janitorial and other menial jobs were some of the few options for work available to black men.”

As he walks the streets of what was once Hogan’s Alley, he points out where old landmarks used to be—the waterfront, railway station and Vie’s Chicken and Steakhouse, one of the most revered local eateries of its time. A quick left turn takes him down an alley parallel to Prior Street, which boasts houses built prior to the First World War still standing. At one time they played host to nights of illicit gambling and drinking. At the eastern end of the alley, Johnstone points out the church that for half a century was known as the spiritual heart of Vancouver’s black community.

“Today, popular consciousness remembers this area mostly for its freewheeling and even dangerous side—the gambling, bootlegging and prostitution. But the neighbourhood was just as much about community, working families and church picnics. Hogan’s Alley had many faces and it’s important to remember all of them.”

Wayde Compton, a founder of the Hogan’s Alley Memorial Project, focuses on telling the stories that reveal the softer side of the East End. “The media coverage of the East End in the last 10 years is so similar to the coverage of Hogan’s Alley in the thirties,” Compton explains. “Both places had sensational fear-mongering associated with them.” This is a perspective the Memorial Project tries to balance by telling the stories of the people who lived in the area and affectionately called it home.

After the completion of the viaduct in 1972, the black community scattered, eventually integrating into larger society. “There is no substantial centre of black people in Vancouver to this day,” Compton says. “It is no longer geographical, but temporal—like Black History Month. Black spaces are created, and people come out of woodwork to talk about the issues that matter to them.”

As a black man, Compton feels deeply connected to the stories and photographs people have shared with him about the forgotten history of Hogan’s Alley. “This history and culture is not about some far-off land—it is right here in my backyard,” he says. “It’s about my identity and that of so many others, too.”