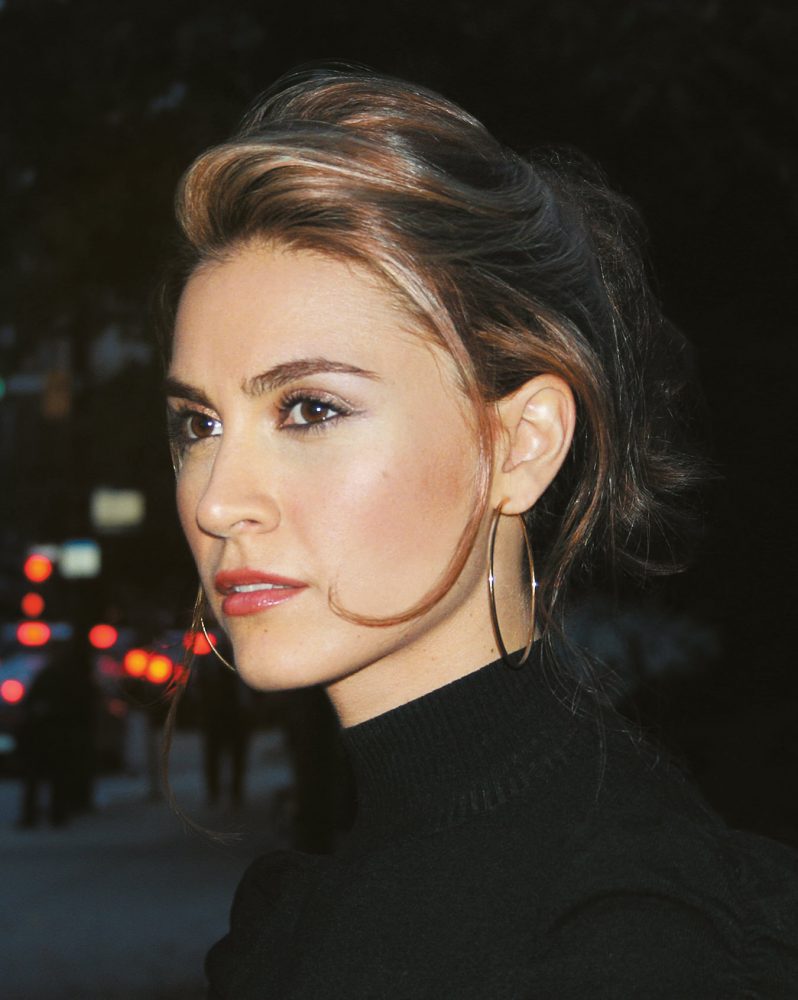

Articulate, educated and undeniably attractive, Nazanin Afshin-Jam could have easily pursued anything she pleased; acting, singing and modeling were only a smattering of her successes by age 25. Instead, her lifelong passion for human rights became her focus, and now, it is her career. “I can’t see myself doing anything else,” says 30-year-old Afshin-Jam. “It is my life.”

Iranian-born, Afshin-Jam first made international headlines after winning the titles Miss World Canada and then runner-up Miss World in 2003. “I competed hoping to gain a platform where I could reach thousands of people with my global fight for human rights,” she says. As the world watched, she spoke passionately about the humanitarian issues she had worked on at the Red Cross, such as landmine awareness, child soldiers, and disaster relief.

Two years later, Afshin-Jam heard the story of her namesake, Nazanin Fatehi—a 17-year-old girl in Iran condemned to execution for stabbing a man who tried to rape her. The gross injustice compelled her to start a year-long campaign that saved Fatehi’s life. The success opened the floodgates, and desperate parents of Iranian children on death row pleaded for her help. “I researched everywhere and found no organization that looked after child execution cases,” recalls Afshin-Jam. “No one checked in on the families, helped with lawyers’ fees, or explained the process. I could only imagine how lost they felt.”

Inspired into action, she founded the not-for-profit organization Stop Child Executions, dedicated to putting an end to the execution of minors, particularly in Iran. Run by a worldwide network of volunteers, many of whom she met during the Fatehi case, the organization has made gains in educating the public and saving lives. Her tireless efforts include many dozens of radio and television interviews, prestigious human rights awards and international invitations to speak about the state of human rights in Iran.

“The job of an activist never ends,” says Afshin-Jam, who frequently wakes at 2 or 3 a.m. to check e-mail or get phone updates from her counterparts in Iran. “Bags under the eyes and muscle tension go with the territory,” as do the death threats she sometimes receives. But Afshin-Jam pays little attention to them. “I cannot live in fear. The real violence is happening in Iran, where the most horrific of crimes are being committed. I live in Canada, a free country, and I have the freedom to speak out, so I make my voice heard.

“Perhaps on a subconscious level this desire to help comes from being part of a family where I have seen it happen,” she says. Shortly after the 1979 revolution, her father was captured and tortured for allowing alcohol and music at his hotel in Iran—activities forbidden by the new, fundamentalist regime. “As a young child, I saw the scars on my father’s back. I know this deeply affected me.”

Afshin-Jam pulls from her bag a page covered in tiny thumbnail photographs—a mosaic of the children already lost to execution. She pauses on one face after another, recounting their stories from memory. “There are those days you don’t win the battles you fight and it is devastating,” she admits, her eyes misting over. “It slows me down for awhile. Makes me sad and then angry. That anger then fuels me to fight back even harder than before.”

But that anger does not taint other areas of her life or make her cynical about her work. She breaks into a happy smile when she speaks of her neices, her three beloved dogs and the many places she has travelled. Afshin-Jam lives in gratitude. “My health, my family, my freedom,” she says, stressing the last, “I am thankful every single day and I never forget how blessed I am.”