“Get real!” I mutter under my breath as an absentminded driver errantly swerves into my lane along Steveston Highway—the maraschino cherry of stress atop an already high-pressure week. Precisely the reason for my sojourn out to Richmond: a conscious choice to put the brakes on the frantic pace of my life notching up toward light speed.

Passing through the temple’s entrance gate, I’m greeted by the sounds of burbling water fountains and recorded chants that soften the traffic’s din. The devout kneel reverently before a statue of the Maitreya Buddha, clutching joss sticks while offering prayers to the laughing Buddha. Delicate tendrils of perfumed smoke waft from the burning incense—I inhale deeply and exhale slowly, releasing some of the tension that has accumulated over the course of my day.

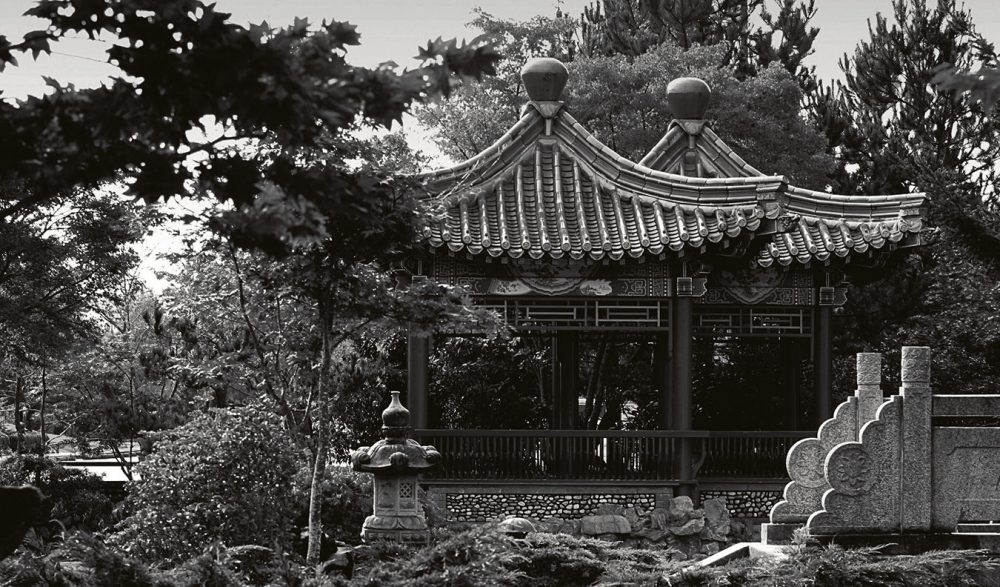

As I meander along the path through the classical Chinese garden and into the Worshipping Square, I contemplate the inscription on a placard cut from the 200-million-year-old granite of China’s Tai Mountain: “Blessing on those who meditate here to be freed from all phenomenal clinging, with the Buddhas always in their minds.” The air is suffused with a tranquility that transcends boundaries of religion and faith, and I become increasingly reflective with each footfall, continuing to decompress.

The intricately detailed Northern Imperial-style architecture is stunning, and I am awestruck by the grandeur of the golden sculptures housed throughout the temple. Four Heavenly Kings stand as sentries at the entrance to the Seven Buddha Pavilion, flanking a towering Avalokitesvara Bodhisattva, the ever-watchful Compassionate One with 10,000 intricately sculpted eyes and hands. Stepping into the Main Gracious Hall, I’m bathed in the radiant splendour of the Sakyamuni Buddha, the largest Buddha statue in North America.

A quick walk down a nondescript side stairwell to the cafeteria leads me to an experience of a completely different sort. Having arrived after the customary lunch hour, I stand and wait quietly to be seated. A gilded reclining Buddha presides over the room, the sole nod to the temple’s lavish aesthetic in this otherwise unassuming space. A handful of diners remain at the long wooden tables clad in orange plastic; their focus is on a Cantonese video of the temple Abbot’s Buddhist teachings. Volunteer staffers scurry to and from the kitchen with minimal conversation—one ushers me to a table and offers me a simple photocopied menu.

In direct contrast to the temple’s magnificence, Chinese Buddhist cuisine (zhāi cài, translated as purification or disciplined cuisine) is simple and spare. It is vegetarian, dovetailing with ancient Taoist and Confucianist philosophical precepts and reflecting the general Buddhist tenet of ahimsa or non-violence towards living beings. In its strictest application, zhāi cài extends this principle to the genus of plant life and avoids the use of root vegetables such as carrots and potatoes. Bean and wheat products are the primary protein sources in this meatless cuisine, and Buddhist vegetarian chefs are remarkably adept at using seitan, tofu, tempeh and agar to replicate meat in traditional Chinese recipes. Buddhist cooking also omits strong-smelling plants—garlic, onion and other alliums, coriander—that might overstimulate the senses and distract a believer’s meditation. Thus, temple food is seasoned lightly and has a clean aftertaste, enabling greater focus on the flavours of the original ingredients.

Signs on each table caution diners on taking only as much as they need. Portions are generous, though, and I depart clutching a sizable bag of leftovers, well sated both in body and mind. Strolling out through the temple grounds, I briefly recall the driver who cut me off earlier that afternoon, the incident all but a distant memory in the wake of my tranquil retreat. A peaceful smile crosses my face as I leave, grateful for the opportunity to unplug and get real.

This story from our archives was first published on Dec 10, 2009. Read more Community stories.