Resting just eight kilometres outside of Philadelphia is one of the world’s most important art collections you’ve probably never heard of. It’s called the Barnes Foundation, and soon this collection of post-impressionist and early modern work will move from the quaint suburban county of Merion to the Benjamin Franklin Parkway in downtown Philly. When it does, one of the most incredible places to see art in North America may be lost forever.

The Barnes Foundation was the pride and joy of Dr. Albert C. Barnes, a man who made his fortune co-inventing and marketing the medicine Argyrol but spent his life collecting art. He counted Henri Matisse, Giorgio de Chirico and William Glackens as friends and amassed over 181 paintings by Renoir, 69 by Cezanne, 46 by Picasso, 18 by Rousseau, seven by van Gogh, six by Seurat, and countless others by masters the likes of Manet, Monet and Degas.

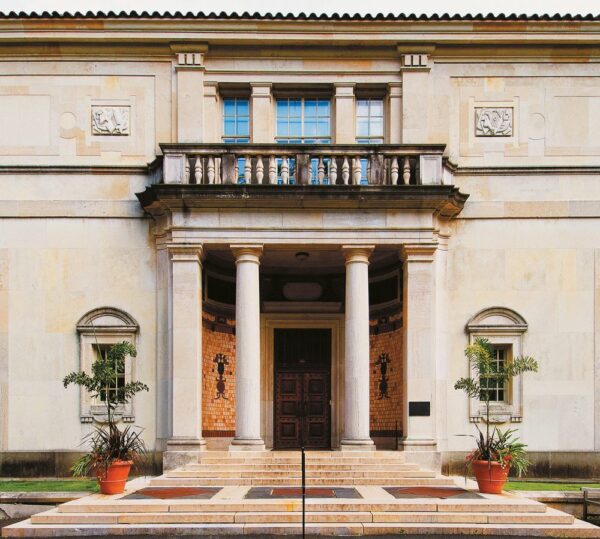

Needing a place to house his collection, in 1922, Barnes and his wife Laura purchased a 13-acre lot in Merion from Joseph Lapsley Wilson, a Civil War veteran and horticulturalist, agreeing to preserve the flora on the property, which included trees planted by Wilson as early as the 1880s. This became the site of the current gallery, a now-historic building designed by French architect Paul Cret, as well as the site of an arboretum of 3,000 species of woody plants and rare trees further planted by Barnes and his wife. The arboretum and gallery became the nucleus of the Barnes Foundation, an organization Barnes created to “promote the advancement of education and the appreciation of the fine arts”. Henri Matisse called it “the only sane place to see art in America”.

From the institution’s small entrance you’re immediately greeted by a room with 30-foot ceilings, the walls adorned with art. Here a Picasso; there Cézanne’s Card Players and Girl; above it, Seurat’s Models; to your left, an oversized Matisse. And on and on it goes. At times your eyes are not sure where to move next; the sheer volume of work is astounding.

For Barnes, art lived everywhere: in antique door handles, the curve of a cabinet, the design of a candleholder. He developed his own theories of aesthetics, believing there were universal elements and traditions evident in all art forms. Throughout the gallery, antique furniture, ceramics, wrought iron, Native American jewellery, African sculpture and other international artifacts are displayed next to, underneath, and above the paintings. As you walk through the collection, your eyes begin to open to all that surrounds you. The S-shaped curve of a hinge seems to mimic a portrait by Renoir. The lines of a chair are similar to those of the trees in the Cézanne above. It is an evocative way to connect with some of history’s most important artworks, and there are a flood of emotions that swell up in you as you pass through these galleries—a sense of mastery, magic and humility. For the art lover, it is enough to move you to tears, both for the beauty that surrounds you and for the potential loss to our collective cultural heritage when this collection moves in 2012.

It is no surprise that the Barnes Foundation move is embroiled in controversy: the collection is comprised of some 2,500 works of art. Following a long and losing battle to prevent the relocation, Barnes’s paintings, artifacts and antiques will be displayed in a downtown museum, designed by New York architects Tod Williams and Billie Tsien. The two have been entrusted to preserve the original layout, room size and “feeling” of the Barnes, but the relocation comes against Barnes’s own last will and testament, which states that the paintings are never to be moved, sold or loaned.

Currently, five of the 24 galleries at the Barnes have already been closed for conservation work, preparing the artworks for transportation. And once the Merion building closes its doors completely in 2011, only time will tell if we’ll ever be able to experience art this way again.

Photos: ©2010 Reproduced with the permission of the Barnes Foundation.