There is an old saying about how the outside of a horse is good for the inside of a man. The same seems to go double for the inside of a dog, at least according to some writers fascinated with what the essential nature of dogs can tell us about being human.

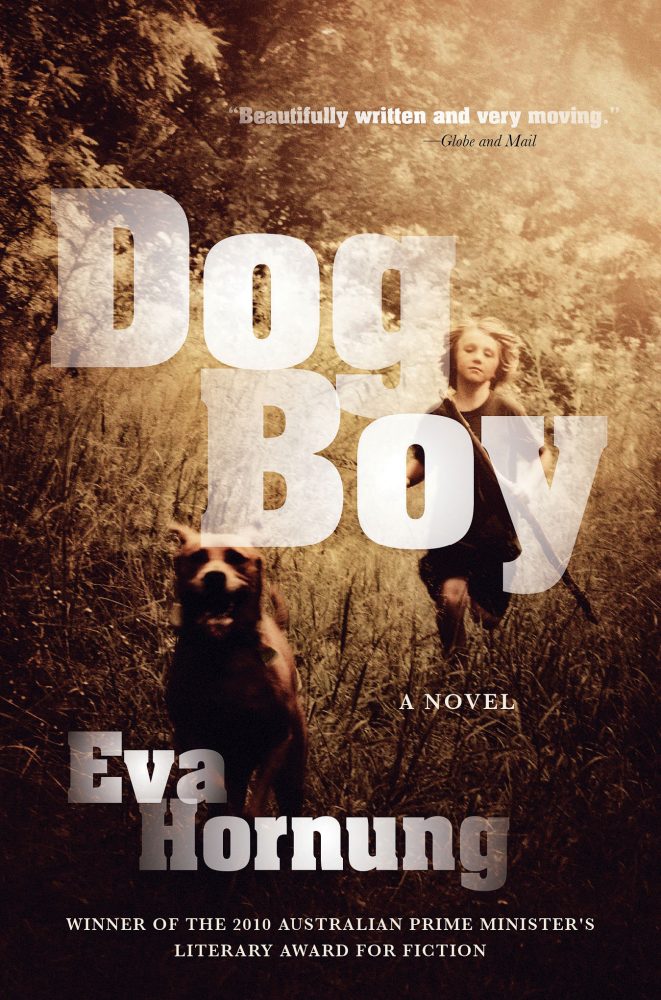

In an astonishing tour de force of imaginative will and narrative agility, Eva Hornung’s Dog Boy (Viking, 2010) follows the life of Romochka, an abandoned boy who is adopted into a feral dog pack in Russia. Hornung was reportedly inspired by the real-life case of seven-year-old Ivan Mishukov to create this startling tale. With precise language and absolute mastery of an unfamiliar perspective, the novel takes us deep inside the rituals and mores of another species. The desolation of the landscape, with its mountains of human garbage, only makes the integrity of the dogs’ lives more apparent. Most painful is when the boy and his pack are interfered with by a human society whose members are notably neurotic and craven.

Romochka recognizes how dangerous humans are, and yet he has trouble staying away. “All people were dangerous, without exception. They were like demons at the fringe of everything important in his world, but they were also familiar … Romochka knew them all without even looking. The loners and the parents, the lovers and the children. He skirted them and forgot them.” Alas, they don’t stay forgotten. Dog Boy is the sort of novel that you want everyone to read so you can keep the discussion going after it’s over.

Melvin Burgess, who is perhaps the biggest chance-taker in contemporary teen fiction, wrote a book that challenges not just our ideas about what constitutes young-adult fiction but also about freedom and responsibility in his powerfully subversive Lady: My Life as a Bitch (Andersen Press, 2001). The book opens with 17-year-old Sandra, who is up to no good. She’s gone out of control with boys and drink and drugs. During one of her escapades, she runs into an alcoholic and they get into an altercation. In a twist that Burgess somehow makes believable, she goes home to discover that the man has turned her into a dog. Sandra then spends the rest of the novel torn between revelling in the life of a dog and longing to return to the life of a responsible young person that she left behind even before she was transformed.

The story is bawdy and explicit and unsettlingly frank. We get to see why Sandra might prefer staying a dog with all the attendant sensory gratification: “Mouse, rat, rabbit, cat … the dug earth, the vegetables pulling goodness out of the ground, the daffodils and the buds, the birds sleeping in the trees, the slugs and snails, the filthy road beyond the fence,” and the shame-free self-gratification of such a life. She misses her family and human society but is conflicted: “Oh, I was in love with Terry, but to run and sniff and feel my ears catching sounds out of the air! But what do you know? Only a dog could understand what I mean.” Perhaps, thanks to Burgess, we get the general idea. The author offers no easy answers, and his refusal to clap a neat moral on top of the story makes it at least as much of a conversation generator as Dog Boy.

Dogs are also moving steadily into other genres. Spencer Quinn’s detective novels featuring Chet, canine sidekick to Bernie, a detective, are not nearly so twee as they might sound. The Chet and Bernie Mystery series begins with Dog On It (Atria, 2009). The critical respect the book garnered from crime-fiction icons such as the late Robert B. Parker and horror master Stephen King has everything to do with Quinn’s handling of the canine perspective. Chet narrates the series, and his perceptions and behaviours are convincingly doggy. At the same time, Quinn manages to generate brisk, nicely twisty plots.

In all three of these titles, it’s telling that the dogs are the better people. The feral dog pack in Dog Boy forms a functional, ethical, and pragmatic society. The life of the stray dog presented in Lady is a trifle wanton, but certainly more honest and forthright than a similarly wanton life led by a wayward teenager, who is drowning in her own lies. In Dog On It, Chet detects while Bernie bumbles. In each case, the writer has gone as far inside a dog’s head as is probably advisable. Lucky for us.