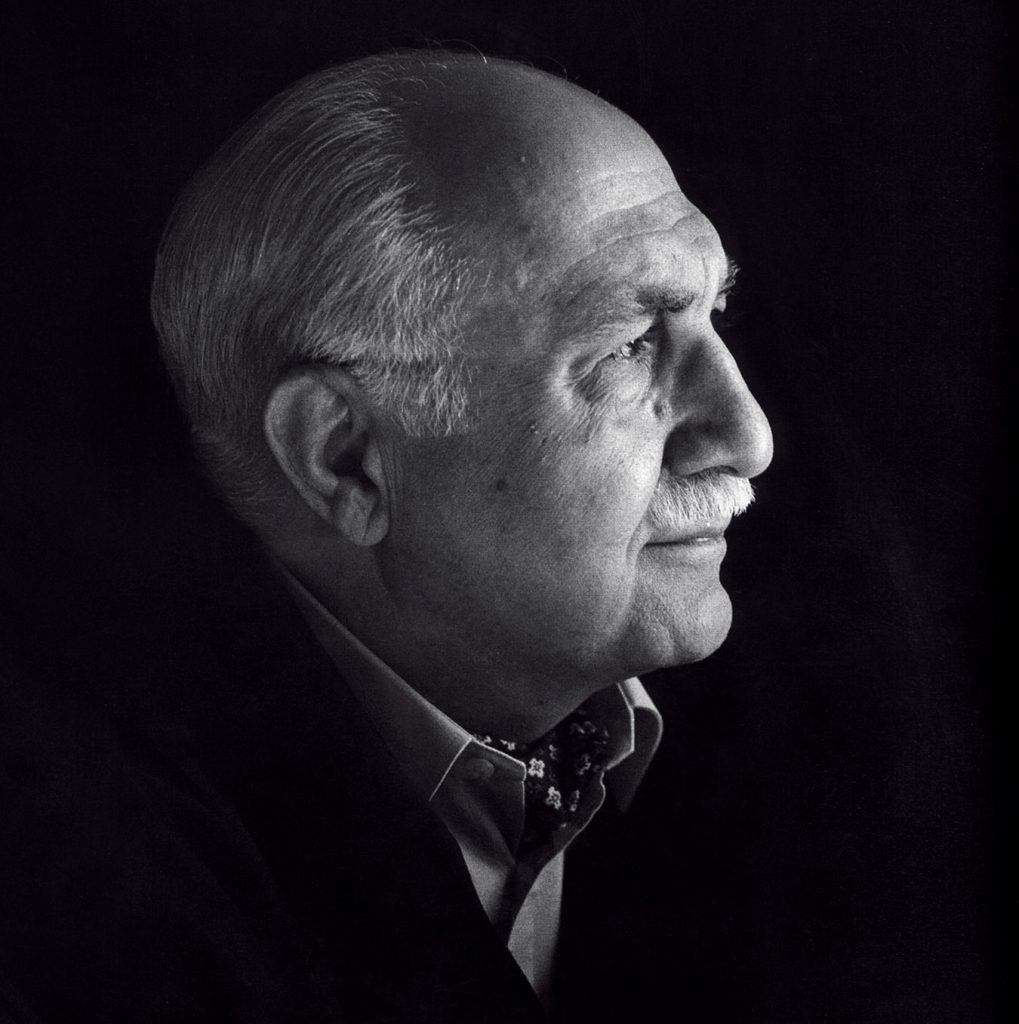

High on the cliffs of Point Grey, among fragrant stands of pine and cedar, sits the Museum of Anthropology (MOA). Designed by the late, great Vancouver architect Arthur Erickson, the MOA is a precise interlay of vertical and horizontal lines of concrete and glass, mimicking the traditional post-and-beam design of First Nations longhouses. Harvard University senior research associate Nader Ardalan, who is also president of the award-winning architectural firm that bears his name, was a lifelong friend of Erickson’s, and he recently journeyed to Vancouver to speak at MOA’s Safar/Voyage exhibition, which showcased contemporary works by Middle Eastern artists.

Ardalan first came to Vancouver in 1976 for Habitat Forum, held in conjunction with the United Nations Habitat Conference on Human Settlements. He and other global thinkers such as Erickson, Margaret Mead, and Moshe Safdie, who later designed the Vancouver Public Library, gathered to debate the challenge of increasing urbanization. The forum bolstered a nascent environmental movement and, for Ardalan, reinforced the idea that contemporary building design should be rooted in the vernacular, or ancient traditions, much as Erickson referenced First Nations design at the MOA. “This museum is testament to the perennial search for identity,” Iranian-born Ardalan, now 74, told attendees at the lecture. “Investigating your own cultural identity is a prime contribution that you can make to the world and to yourself.”

Ardalan’s talk, sponsored by the Hassan and Nezhat Khosrowshahi Distinguished Lecture Series, probed this idea, addressing holistic sustainability as a way to inform the creation of environmentally adapted, healthy, culturally relevant, affordable, and aesthetically enriching communities. Other than the MOA, Ardalan says, “I’m surprised that I don’t see any real major impact of First Nations on Vancouver. It could gain an indigenous character, and out of that might come a valuable new creation.”

Such discourse about cultural relevance has reached a point of urgency here and elsewhere throughout the world, as peak oil races toward a convergence with ecological crisis brought about by climate change. Vancouver is a uniquely beautiful city, but as Ardalan points out, it is not currently as sustainable as it could be. Low-density urban sprawl is dominated by single-family dwellings that are highly permeable and thus require considerable energy for cooling and heating and municipal infrastructure for services. Extensive transportation corridors carry single-occupancy, gas-guzzling vehicles that “contribute to global warming and sea-level rises that could endanger low-lying areas of Vancouver,” says Ardalan. Conscious of such ecological threats well before his time, Ardalan designed one of the first sustainable, solar energy–based cities in the late 1970s called Nuran, the City of Illumination, which was to be built near the historic city of Isfahan in Iran. (The 1979 Iranian Revolution halted plans for its construction, but Ardalan has since built aspects of that city elsewhere.)

His latest project is as senior editor of a long-term project called the Gulf Encyclopedia for Sustainable Urbanism (GESU), a groundbreaking research study at Harvard Design School sponsored by Msheireb, a subsidiary of the Qatar Foundation. GESU is documenting and analyzing 10 representative port cities’ architecture and the relationship to culture, the environment, public health, and the economy of the Persian Gulf. In addition, GESU is exploring ways to ensure that future urban growth is informed by vernacular design principles that are compatible with the forces of wind, heat, cold, and water and that seek harmony rather than dominance. “Man and nature—the right path. Man over nature—madness,” says Ardalan, who is the co-author of The Sense of Unity: The Sufi Tradition in Persian Architecture, which is studied by architectural students worldwide.

The Middle East can boast a few far-sighted projects, including the experimental and renewable energy–based city of Masdar outside of Abu Dhabi. Currently under construction, the city is compact, with mid-density courtyard structures and narrow streets to optimize shade, encouraging walking. Clean-energy vehicles will provide transport within the city, and a personal rapid transit system is also being piloted. Rooftop solar panels will generate electricity, and most of the water will be recycled. These urban complexes, says Ardalan, signal the possibilities that await those designers who shift from towns and buildings that depend upon fossil fuels to those that draw upon the wisdom of vernacular design to work in harmony with nature. “It’s not just about getting a building to look better,” he says. “It’s about human survival.”